March 18 -24, 2012: Issue 50

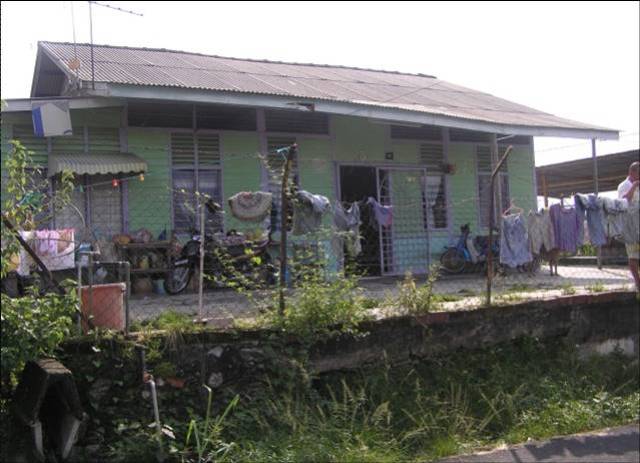

Above: Our hovel, 50 years on, now with new owners

Above: The tropical jungle has reclaimed my clearing

Above: I caught catfish here half a century ago

Above: My favourite delicacy – Durian (King of Fruits)

Above: Fish for sale but beyond my means

Above: Unaffordable Roast Pork, Duck and Chicken

Words and Images Copyright Huang Zhi-Wei (aka Reg Wong), 2012. All Rights Reserved.

I was a scavenger

Huang Zhi-Wei (aka Reg Wong)

Have you noticed that Warringah Mall’s Country Growers bears little resemblance to the green grocers of yesteryear? You know what I mean? Remember the bare-boned stores operated by first-generation Italian immigrants forty or fifty years ago? They are not like those anymore. Today, green grocers are still mostly operated by ethnic Italians – but now by those born here - and on a scale their fathers never imagined possible. Vumbacca’s in Dee Why is such an example and the renovated Country Growers in Warringah Mall ranks as one of the best on our North Shore - for variety, scale and visual appeal.

On this particular day, my attention wasn’t so much captured by the flawlessly arranged produce as by a young Indian employee who was preparing Chinese cabbage for display. He was almost robotic, as he reflexively wielded the sharp knife with a dexterity obviously acquired from weeks, perhaps even months, of practice. He picked up one Chinese cabbage after another from a box brimming with the vegetable. Sure, his task was mindless but he executed it with effortless alacrity and a graceful fluidity that was fascinating to watch. He selectively sliced off every one of the cabbage’s outer leaves that was less than perfect, letting it drop into a large bin, and then placing the tucked-n-nipped product alongside its equally-faultless fellows on the shelves – all in one automated seamless motion!

Looking at what I judged to be still good-enough-to-eat cabbage leaves going to waste, I was immediately stirred to ask, “Are you giving the trimmings to anyone?” But the question remained unuttered, suspended above my pursed lips, as my mind transported me back to a place far away and a time long gone.

* * *

It’s now half a century since I was a scrawny kid surviving in a jungle clearing but, in spite of the passage of so many intervening years, I still remember how I scavenged to survive. Yes, I scavenged! Even today, in Seremban, my old town’s market place, vendors are still wont to removing the outer layers of limp and moth-eaten leaves from the Chinese cabbages. My rolê in our unscripted survival play was to gather these trimmings and bring them back to our hovel for sorting into what was suitable for pigswill and what was salvageable for turning into salted cabbage for our own consumption.

The mere memory of what was once such an essential struggle for daily survival jolted my mind to return to the present and prompted me to look at myself, finger the Rivers shirt I wore, gloat at the Rockports on my feet, and feel the bulging wallet in my pleated tailor-made trousers. With a breath born of resignation and acceptance, I whispered in relief. “Well, old boy, haven’t you come a long way since those bad old days?”

We think that scavenging is an endemic way of life in the Philippines, India, Mexico and most third world countries. Here in the midst of overwhelming plenty, my Aussie children and grand children can’t even conceive of anything remotely resembling scavenging. But I can … and not just for rotting vegetables discarded by green grocers.

* * *

The War was over, the ubiquitous Japanese were vanquished and driven back to their islands, and the British had reclaimed Malaya as another one of its sovereign territories. But pervasive peace was elusive. The war against the Japanese aggressors was now replaced by a fight against the Communist terrorists who felt they deserved a fair share of the spoils of a successful joint campaign.

Compounding the problem for the army was the empathy the jungle-based terrorists enjoyed from the poverty-stricken masses that supported them with supplies of food. To isolate the terrorists from their sympathisers, the-then British High Commissioner, later to be Sir Gerald Templar, devised an innovative scheme to corral all people living outside urban areas into fenced and guarded villages. My family was among those shepherded into an enclosed kampung baru (“new village”) where, although in relative safety, we still needed to keep body and soul united.

As an emigrant from rural China, my father was untrained in any trade or profession that made him employable in Nanyang (South-East Asia) to which waves of Chinese and Indians flooded to escape the dire poverty in their own motherlands. Adding to my father’s woes was his addiction - and enslavement - to opium. He just didn’t have either the will to work or the strength to drag himself out of his smoke-filled den. Thus, the unenviable task of supporting an ever-increasing family fell upon my mother’s tiny but strong shoulders. I am not boasting when I claim that it was our family who lent veracity to the adage that “the rich get rich but the poor beget children”. And before I forget, I make another claim : our family was so poor we actually raised the status of the proverbial church mice!

When you are hungry your primitive olfactory glands develop a disproportionately heightened sense of smell for food. Even now I remember with unbridled embarrassment that whenever my nose picked up the wafted aroma of beef stewing in a pot of curry or chicken frying in a wok - from where else but the neighbours’ directions? - I would salivate involuntarily, and profusely, just like one of Pavlov’s dogs. Why is it that we crave protein, as in meat, more than we crave carbohydrates, as in rice, whenever we’ve been without proper nourishment for any prolonged period? I have my own explanation but you may want to formulate your own.

On days when the tropical gales raged and monsoonal rains poured, I would stand close to our neighbours’ mango trees. Even though not yet eight I was already wise enough to know that ripe mangoes simply gravitated to the ground when buffeted by strong winds and pounded by torrential rains. And it was a case of Finders Keepers. On clear days, I would venture into the padi (rice) fields and forage for the eggs of water fowls. By the time I reached my teens, I would fish for catfish with a makeshift bamboo rod whenever the streams were full from a downpour. At night when the fruit bats enclosed their wings around the bountiful tropical fruits in a rapture of feeding frenzy, I would use my shanghai to bring one down to place over an impromptu charcoal barbeque. Ah, the smell and taste of glorious meat! What memories they evoke!

* * *

My days of scavenging for discarded vegetables, foraging for birds’ eggs in padi fields, and catching catfish in polluted streams are now interwoven into the fabric of my inextricable past. Today my larder is overflowing and the next meal of fresh fruit and vegetables, roast meat and dessert – everything that was once foreign - awaits me and is only a few steps away in my state-of-the-art kitchen. And does that erase the memory of my beginnings?

Traditional Chinese people believe that if you happen to see a white peahen - that is more beautiful than a bride adorned for her husband - good luck will follow you for the rest of your days. But I have never seen a white peahen. So how can I explain my current position of abundant blessings except that it is entirely traceable to God’s generosity? And why has He chosen to smile so benignly at me? I don’t know. I am truly stumped for an answer. But it’s a mystery I am willing to accept … humbly and graciously.