August 17 - 23, 2014: Issue 176

Harry Bragg

The Story of a Life Well Spent

As I sit here at the age of 90 I can look back on a life well lived. Although recent years have certainly been marred by pain and physical limitations and I can no longer enjoy the activity on which I once thrived, I can honestly say there are only a few regrets to cloud my reminiscences abut the past.

Mine has been a life enriched by two satisfying careers - one planned the other almost accidental - and by the sort of travel and adventure that I feel privileged to have been able to experience.

While some of the more strenuous of these pursuits may have contributed to my present physical difficulties, there is not much I would want to change.

I have plenty of time now for reflection but, since my writing is much slower than it once was, the memories captured in this story have been compiled from recordings I made with a journalist between March and August 2011.

Let’s start at the beginning.

The Early Years

I was born in Manchester on October 3, 1923 in a place called Chorlton-Cum-Hardy, then a village on the outskirts of town that took its name from the two farms that were once situated there.

I lived with my parents and older sister, Joyce, in a house similar in style to those you see on

My parents came from different backgrounds. My mother, Margaret, was from Westport inCounty Mayo, and was part of the exodus of Irish women getting out of Eire bec

Left: Margaret Bragg (nee Ruddy)

My father was from a little village called Stockdale Wath in Cumberland, north of Carlisle, which everyone pronounced as 'Stoddlewath', but he came down to Manchester for work. He got a job in a grocery shop, then, when it was sold, he transferred to the co-operative society grocers. I've still got a picture of him in front of one of his window dressings which, coincidentally, was about Australian goods — 'Buy Australian; the Best.'

I was the middle of three children. Joyce, who still lives in Brighton in the UK, was two years older and takes her name from the Irish side of the family — Joyce was my great-grandmother's name. There was another son born after me, John, but he died a short time afterwards and I was too young to have any memory of him. I think he is buried in the

Right: Harry and Joyce

Our house was in

Downstairs we had a front room, the parlour, for receiving guests, but the family spent most of the time in the living room, which was between the parlour and the kitchen. It had a wood fire and that's where we would listen to the radio or do things like play cards and charades.

The backyard was small — probably no bigger than a living room — with an outside lavatory attached to the house. There were no toilet rolls, just cut up paper and it was always my job to very carefully tear the newspaper into strips to hang in the loo. Another memory of the lavatory is that it had a sloping slate roof and I used to use to practice slab climbing. There was also a cellar which housed my father's stores of canned food in a meat locker. He was able to bring stuff home from the Co-op before it was rationed out. He could get some for other people too, like the Wilsons and his friends that came round to play 'chase the ace’ on Sundays. The cellar also stored coal, which was delivered from the road by lifting the grate where it fell into a bunker. The washing was also down there in a galvanised iron tub, using a 'dolly' which was a wooden pole th three legs on the bottom that you mushed the clothes around with.

When the war came they put in an air raid shelter that virtually took up the whole back yard. It was unusual in that it was brick rather than the teal Anderson corrugated iron-style shelter. It wasn't elaborate, just an open structure. If the air raid siren went off one was supposed to get into it but I think, bec

I can still visualise the neighbourhood. Next door to the right of us was the Yates family, whose father rode a bike and I remember took great care of it.

The d

I still have a post card Norman sent me for my birthday.

Some of my other early memories revolve around cars; like the day one of our neighbours knocked our front wall down. There were only about two cars in the street at that time. The other one belonged to the choirmaster who lived a few doors down. His car had a boot that opened backwards with two seats in it. Once, when he was going for a drive to Rhyl, a sea-side town in Wales, he took Joyce and me. It was very nice of him and we were thrilled as it was something not many people got to do.

Right: Harry aged 15.

Most people at the time relied on buses, but the school I went to was in the park at the bottom of our street so my sister and I only had to walk through the park. Then, when I got the scholarship to Chorlton, it was just the other end of Beechwood Ave, 1 50m at the most, so I was able to do it all walking.

Chorlton was a high school but much to my joy, while I was there, it changed its name to Chorlton Grammar - Grammar schools had a better standing. I was a good student, probably in the top three at my school. All of us put in for Manchester Grammar, but I missed out. Most of my friends, including Bruce Herbert who finished up as my best man, then got their parents to pay for them go to Hulme Grammar, which was a private school.

Had I not got the scholarship to Chorlton I know my father would never have agreed to pay for me to go to Hulme. He just wasn't like that. When war was declared and our school had to be evacuated, it was to a very, very good public school called Rossall near Southport; a really posh school and I thought, ' Boy, can go around saying I went to Rossell' but he said, ' No. You're not going. Get a job.'

Somehow it is ingrained into you that the higher you go in education the more successful you will be. But, I had no choice in the matter so I went to work for an accountancy firm in Manchester. It wasn't that terrible bec

I was able to pick up the accountancy work without too much trouble. Basically it started with adding up and you picked the rest up as they gave you other jobs. did register to do some accountancy study. I thought, ' Okay, I'll sit their exams' although I didn't really want it to be my career, but then one of our family friends who used to come around on Sunday nights to play, got me a better job at The Refuge Assurance Company where he worked.

I don't have any really dominant memories of my parents. I think my father was quite an upfront sort of person. He made friends, but that was possibly bec

As a parent, he was strict and quite hard, but that may have had something to do with his background. He came from an area up inCumberland which was fairly isolated, no really big towns, and they had to scratch a living doing whatever they could do for anybody who had land.

We used to go up to visit his family, who lived all around Carlisle, and I remember meeting a cousin there who was also called Harry Bragg. They were all quite stern, no-nonsense people, except for one called Aunty Polly who was married to a relative of John Peel. (John Peel was a gentryman who was made famous by a song). She was the nicest one. I remember I rode my bike from Manchester to Carlisle to stay with her once when I was 15 or 16. It was quite, a good long ride but I made it in two days. Slept under a bridge one night.

John Peel's grave

"Do ye ken John Peel with his coat so gay.

Do ye ken john Peel at the break of day'

Do ye ken /on Peel when he's far far away

with the fox and the hounds in the morning"

My father wasn't the sort of person who would show his emotions. He could be demonstrative, but that was mainly to my sister. He used to call her Joycie Boycie but he didn't call me Harry anything, not that that struck me too much at the time. But, with my father, there was no doubt who was the boss. If I did anything wrong he had a big, old-fashioned razor strap with a buckle end that was always hanging up and I got one for every misdemeanour, even slight. It was the way of disciplining your kids, I suppose, at that time.

Right: Walter Bragg.

He was always keen to push us on bec

He also pushed me to be athletic. He wanted me to be the Victor Ludorum - that was the most prestigious athletics award at the school, for the winner over the 100yds, 220yds, 440yds, high jump and long jump. He would ride a bike up the hills and I had to run along beside him, then we used to paint a line in the cloughs and practise long jumps. Anyway it paid off. I've still got the award for being the Victor Ludorum for 1937.

My mother (Margaret nee Ruddy)was a typically Irish person in that she hated the British. Growing up, the Irish influence was quite strong. For example, we used to listen to Radio Athlone, and we saw quite a lot of the Irish

She was softer, definitely, than my father and I was probably closer to her. I think she was quite proud of me. I can always remember she used to hate me having dirty hands and she would make me scrub them. She thought that was terrible, having dirty hands. I think she thought only labourers and common people had dirty hands and I shouldn't.

Then there was my sister Joyce. We have always been quite close - have a photograph of us somewhere sitting in front of the camera holding hands. We started to lose touch with each other a bit when we passed the scholarship to go to secondary school. She went to a central school, which was quite a long way away, then during the war she went into the air force and that's where she met her husband Ray.

My mother died from heart problems at 82, about two years before my father. I wasn't there at the time of my mother's death as she was in hospital and we didn’t realise that she was so ill. My dad arranged for the Order of the Buffalos to escort the coffin with a marching band. The Order of the Buffs like the Masons.

I was with my dad when he died. I think my father had numerous heart attacks over the years, but he always implied it was a problem with his arm, he ignored it and never got any treatment. He went to hospital and the doctor contacted us and said, "I think you ought to come up". Joyce and Ray were there also, but they went out to get something to eat when my father gave the typical 'death rattle’ and his last words to me to me were, ‘It's a bugger Harry.' Then he was gone. I went out to find the doctor and said 'I think he's died', which the doc confirmed.

The War Years

I was 16 when the war broke out and 18 when I volunteered for the Young Soldiers Tank Battalion. I always connect that period with 'In the Mood' bec

Despite the war, life in Manchester seemed to go on pretty much as usual, except for the rationing and the sound of the German planes flying over. Then of course came the real blitz where they bombed big towns. I was actually in the cinema when Manchester was bombed. One of the firebombs came through the roof and set things alight. When we dashed outside we saw a lot of other bombs had gone off.

Once I was taking a girl, Audrey, home and so much shrapnel was coming down and sparking on the road that we had to shelter under the eaves of a house. I would have liked to turn around and go back but I thought, 'I'd better be a gent and take her all the way.'

Early on in the war I joined the LDV, the Local Defence Volunteers, which involved things like every so often having to go and guard a power station, to see that nobody came in and destroyed it. Later I moved to the Home Guard, which was like an upgraded version of the LDV, but with some different duties and more weapons training. I remember when I actually then got into the Young Soldiers Battalion my father got a letter from the Home Guard saying that I hadn't done my duties for a month so he phoned them up and said, 'He's in the army mate. Wake up Home Guard', or something like that.

After I left Bovington, where we trained, I got posted up to Northumberland and dumped into an Irish Brigade, the 5th Enniskillen Dragoon Guards. I hated it. They did have tanks, but all I had at that stage was a Bren gun carrier which was just a little thing. It was a poor sort of place too; we were in huts that weren't much good and there were rats and so on, so I was dying to get out. I volunteered for all sorts of things and eventually managed to get a transfer to the 5th Royal Tank Regiment - the Desert Rats — by then back from the Middle East and based down in Norfolk.

I was there for a few months before D-Day and we spent most of that time preparing, doing mock war games, and waterproofing the tanks and all the drills associated with getting ready for

We had about a week's notice before we left. That was a week where we had a lot of freedom so I decided to shove off to Manchester - and got c

It was reasonably tense leading up to the actual departure. I was frightened, certainly, bec

Harry documented this part of his wartime experiences in an article “D-Day and Normandy Memories”, which he wrote in 2004 after travelling to

In 2004 I had the great privilege of travelling with IMPS, in Richard King's Jeep, to the 60th Anniversary of the "Second Front". For me, it was a very exciting and rewarding trip. It seems right that I should do something in return, hence this personal account.

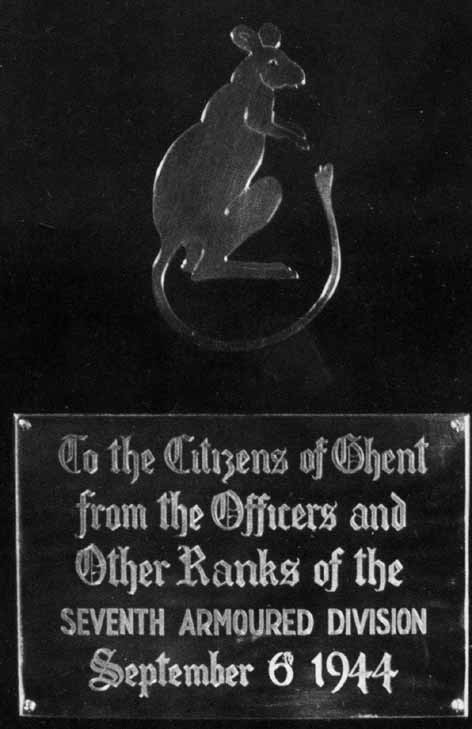

First, the background. I was a driver in the 5th Royal Tank Regiment, which was part of the 7th Armoured Division - "the Desert Rats". Our shoulder flash was a jerboa, which was occasional mistaken for a kangaroo, and we were asked were we Australians. I wasn't then but I am now! The 5th RTR, the 1st RTR and the 4th County of London Yeomanry made up the 22nd Armoured Brigade.

This Brigade was stationed in the Ipswich area and we embarked from Felixstowe in LCTs on the 4th June. LCTs (Landing Craft Tanks) were only meant for short trips and had no separate accommodation for the tank crews; sleep where you can and cook your own food. We sailed through the Channel in broad daylight and could actually see the coast of France, but as far as I was concerned, they never fired a shot!

When we got to the assembly area, the weather had worsened, delaying the invasion somewhat. Eventually, I drove our waterproofed tank off LCT in the early morning of D-D + 1 - 7th June. That a long time on an LCT! The landing was close to Arromanche and seemed a piece of cake as infantry had cleared the coast in this area already. In a waterproofed tank you have to drive using periscopes as the driver's door/visor is sealed. I thought to hell with that and opened the door and abandoned the periscopes. Clever Dick! I didn't think there would be bomb craters but there were and we went down one and into it, taking in water before I could slam the door shut.I came out of it wet but OK. But was nearly responsible for losing the tank before we even got to terra firma! That was the first mistake.

Apparently the Division's intention was to capture Villers Bocage and Aunay sur Odon to take the high ground beyond. Bocage country wasn't much good for tanks. It was a mass of small fields surrounded by bushes and hedges, all riddled by muddy tracks. I didn't like it. The enemy could be only 5 yards away before you could see them. Ugh! But there were quite a few more open areas and many villages which were a different matter. There would be enemy tanks to deal with. On my way to Villers, we parked in a gap in the hedges and were shot at by an 88mm, armour-piercing shell. How could I know it was an 88? Well it hit something only yards away in front of my tank, possibly a disused railway track and ricocheted up in the air, showing green tracer. An 88! (Calls in later Housey-housey games became "all the 8s, 88 - bale out").

All of a sudden there was a loud bang and flames broke out around the turret. The inexperienced 2nd Lieutenant crew commander shouted "bale out"! Which they did but I couldn't bec

It is fairly well known what happened at Villers. We didn't actually enter the town but the 4th CLY did, at the unfortunate time when an SS Panzer division arrived from the east with Tiger tanks. They cut off two squadrons and destroyed the other. That was the end of the 4th CLY. They were either captured or killed.

It also signified the withdrawal of 22nd Armoured Brigade, with the 5th Tanks taking up the rear guard, carrying infantry on them. Guess who was driving the last tank? Yes, and at last light we retreated. Any movement behind us would be the now aggressive enemy. Not a stress free journey to say the least. All this in probably the first week from the landing. But that wasn't the end of that part of

About a couple of months later I was back; this time in a new tank, a Comet, I think, which had been great to drive in the battle of Caen and the champagne country to its south-east. But suddenly the 7th Tanks were diverted back to Aunay sur Odon, four miles south of Villers! It was a tiring overnight drive and you couldn't doze off if you were the driver. We, that is a different crew from before, parked directly opposite a farmhouse at short range but I presumed it must have been checked out. Tired out, I loosened my revolver belt, closed the drivers side-opening door, yes, Comets had side-opening doors! And I dropped off to semi-sleep, presuming the others would be on watch.

When a tank gets hit it sounds something like two electric trains crashing head-on at high speed. You don't have time to think at all but just get out of it. There's also a big flash of fire and burning. I was out like a flash but attracted fire from the farmhouse. I got behind the now brewing up tank and grovelled in the ground. The three in the turret, unfortunately, were killed. At last another tank dropped a smoke bomb and I ran along the line of tanks and dived into an enemy slit trench. At this stage I thought there must be better things than this to do when you are only 20.

I also discovered I was quite a good runner bec

The break through followed and it was much better and fewer mistakes. But that's another story.

My 21st birthday was on the 3rd of October, 1944. The Germans were retreating east and we were in leaguer (a circular formation of tanks like a wagon fort with the jeeps holding fuel kept in the middle) somewhere near Hertoganbosch. Another member of our tank crew tossed up to see who should do none or double watches. I got the two, and the night of my 21st was spent listening to every sound thinking it was the enemy, it was probably only wildlife in this wooded area.

Slip Barker was the best driver and he drove C Squadron leader’s tank. When Slip left he recommended me for the job. I used to wear a cravat and the squadron leader, whose name was Crickmay, kept saying ‘Oh get that bloody thing off’ until one day we nearly got hit again by a German with a bazooka in a hedge. We were stationary and suddenly I could hear shouting. I couldn’t see over the side of the tank so I thought the only thing to do was to get the hell out of it. The German fired the bazooka just as I moved forward, so Crickmay said, ‘I think you’d better keep wearing that cravat; it’s lucky.’

Right: Wearing the lucky cravat.

Something I'll never forget was seeing a tank driver named Benny Inwood - I have remembered that name ever since - he got shot. I was about 20 yards away. He had his leg shot off but I saw him get out of the tank and run about 20 or 30 yards with only one leg. There was no other leg. He was doing it on one leg but he obviously must have thought he still had the other one.

After the initial retreats we continued the push through France and up towards Germany with less resistance. The Germans by then were trying to protect their borders from all sides and retreating so it was easy to invade, but many of them were trying to cut across to get back, so they were still a bit of a nuisance. You always had to watch the flank. I remember big church towers where they had lookouts so they could see the tanks coming.

We went on into Caen, which the Yanks had bombed and devastated. We walked around asking the Germans 'Haben sie, in dieses h

We were actually the first tank into Belgium - there is a plaque inGhent noting that our tank was the first to go through - and the first into

We were actually the first tank into Belgium - there is a plaque inGhent noting that our tank was the first to go through - and the first into

We were supposed to keep going into Denmark but of course by then the Germans were retreating and getting out of Denmark.

One incident I remember at that time was a shocking thing. We were parked outside a substantial farm house where two German soldiers were giving themselves up. The Brigadier rolled up in a scout car and shouted "Take them back in and shoot them. The Germans have been shooting our prisoners, so give them a bit of their own medicine". I took them back in and fired two shots into the air and waited until I judged the Brigadier had gone somewhere else. What an easy thing to say and what a hard thing to do. The two Germans were very young and they thanked me profusely for what they thought was saving their lives. They were taken prisoner instead.

Finally came the liberation of the prison camp at Fallingbostel. Not by the 7th Armoured Division, as a squadron was sent in only to find that the main gate was guarded by the British 1st Airborne Division who had taken the camp earlier. It was memorable to see the looks on the faces of thousands of men coming out of captivity to new found freedom. Some were from the 4th County of London Yeomanry (4th CLY) who had been taken prisoner at Villers Bocage about a year earlier and a leave party whose truck had taken a wrong turning a couple of weeks earlier!

Prisoners of Fallingbostel.

There was an imprisoned Sergeant Major in charge. I had to take something to him and found he even had an office with staff upstairs in the main building. They left him there in command of the ten thousand British and Americans and twelve thousand other POWs.

On a lighter note, I remember at one stage we were in a little village on the river called Wavelfleth. Crickmay was keen on sailing so we all had to pinch boats and sail them around — a good indication that the war was really over by then. Once he even sent me off to

Right: on the river Wavelfleth.

When the war was effectively over we were based in a camp near the Kiel Canal. The way they worked it, you got a number based on the number of days you had served and you had to wait until your number came up to be demobbed, then you went to a unit where they took your army uniform off you and they gave you a civvy suit - which notoriously never fitted.

It was more than 18 months before my number came up. That was a funny period. You didn't know what was happening and you weren't very important anymore bec

I think at that stage they were just organising us to not get bored. I remember once I had to escort some German soldiers in a train. I had to walk up and down showing my rifle - which I probably couldn't shoot; I could only fire guns from a tank. There were odd things like that we had to do.

We had bike races and played a bit of rugby in a league with other regiments. One of the rugby players was the captain of the Wales rugby team, who was very famous at the time. He decided I was good at running and breaking through but I was no good in defence bec

Ironically when I got back to Britain the doctor said, 'You're disfigured with this. You should have a pension' so I got a pension for something which was my own f

Naturally I was overjoyed when, finally, it was my turn to get out. I handed over my uniform, hopped on the train and headed home - in civvys of course that didn't fit. There was no fanfare when I got there. No one at the station and no welcome home party. I think I just arrived unannounced at the front door and, by that time of course, I was feeling that I was a man - a bit old for parties or anything like that.

Today I regard war as the most stupid thing ever. There are other ways of settling disputes rather than going and killing each other, but I must have had a different attitude at that time bec

Looking back, though, I think it was such an unusual period in your life that there would have been things you gained from it, like getting to know yourself better through all these experiences; knowing how you can be frightened and then the opposite. Facing fear and then being able to look at it in a different way and feel, 'got to do my best.' In one respect at least I can most definitely say I left the army a different person - I was a 7 stone weakling when I enlisted. When I left I was 11 stone 4. By then I also had a much clearer idea of what I wanted to do with my life.

A New Career Beckons

The idea of becoming a teacher had arisen while I was still in the army. Bec

As it happened, none of those they did see got passes. They all failed. I was disappointed I missed the chance but I thought, 'Oh well, I'll do it when I get back to England.' When I did go for the interview I managed to accepted based on just one book. The only thing they asked me was what was I reading, or, what had I just read. Then: 'Tell us about the book'. They never asked me any other questions just, 'Talk about the book', which I did and they said, 'Yes, you're through.'

But it didn't happen straight away. I had to wait to get the allocation to go to Bamber Bridge Teachers' College so I ended up going back to the Refuge Assurance for a couple of years. Employers at that time were obliged to give servicemen their old jobs back, but I still had the feeling the Refuge wasn't the place for me. And it was hard bec

Dorothy has described meeting Harry and their courtship.

"There must have been five or six girls at the Refuge who used to sigh heavily whenever Harry went past. He really was an extremely good-looking young man. There was a youth hostel weekend we both went on with a whole crowd from the Refuge. That was the first time we really got into conversation and he asked me out. Then on the very first date he said to me, ‘If you’re going to start going out with me you can pack up all the others. I don't want to be part of a crowd ' That was on the very first date. So I did

Apart from the fact that he was good looking, Harry was also different. He was engaging in conversation and he stood above - not physically - but he stood above the other guys there. There was something in him that he always knew he was better and I think that came through.

It was six weeks later that he proposed to me. We had been to my next door neighbour's 21st birthday party and we were walking home. He'd had a few drinks, we all had, and he stopped me and asked if I'd marry him. I looked at him and said, Ask me in the morning when you 're sober.' The next morning I was in the kitchen at home and I was looking in the mirror and he stood behind me and said, "Okay, will you?" I just said "yes". That was New Year's Day. We didn't actually get engaged with the ring until April and then we were married in the August.”

Dorothy and I were married at Rhodes Parish Church on the 14th of August 1948 and the church was packed. Amazingly, it was all organised within six weeks, including Dorothy's mother making not only Dorothy's dress but all the bridesmaid's as well. The bridesmaid's dresses were in two shades of green, which my mother said was bad luck.

We had a great reception at the upper room of the church hall. An army friend of mine gave us a crate of beer and a book called 'Bedside Stories' for a wedding present.

Right: Dorothy and Harry

The following day we left for a week's honeymoon in Morcambe.

At first we lived in two rooms in a huge run-down mansion in

We went back to Dorothy's parents to have a bath and for her Mum to do the washing each weekend. It was the days of food rationing but as my Dad was a grocer, we got a pound of bacon and a dozen eggs every week from him somewhat illicitly.

At Easter 1949 I went to Bamber Bridge and Dorothy went back to her parents home and I lived in digs at the college. We weren't able to see each other too often bec

I used to watch Manchester United bec

The librarian at Bamber Bridge organised a three week trip to Paris and theLoire Valley. It cost £12.50 and we had to meet everyone at Victoria Station,London. We put an advert in the Manchester paper asking if anyone could give two poor students a lift to London, and we got one, from a Jewish couple.

Our accommodation was in school dormitories and double room for couples. We saw the Moulin Rouge and had a night at the opera. In the Loire Valley we visited several chate

I did an extra three months physical education (PE) extension course (My subjects were Maths and PE.) which ended in June, 1950. By this time Dorothy was 5 months pregnant. When I finished college I decided I'd had enough of Lancashire - with it's 'dirty old towns' and all the rest of it - and I would only accept jobs in the south, so my first job was at Faversham School down in Kent.

My next job was at Sheerness Technical School, which is where I got the news that Dorothy, who was still in Manchester, was in labour. My friends, the S

There were a few things of note at Sheerness. One of the teachers there was a boxer. He was a very unusual, though likeable, guy. He used to hang kids out the window — and it was a double storey building! Consequently, the Education Committee was very happy to see me employed there so they could get rid of him.

I remember once at Sheerness getting rapped on the head by a teacher bec

Another time an HMI (Her Majesty's Inspector) came around and said to me, "Mmm, I've got some of your records here. You ought to read this book— an old fashioned mathematics one that I think I had read anyway. "And you should take this maths course that's going on Friday evenings." I said, "I would, but I'm the tutor of it." - he wanted me to get some more education in maths in a class I was already teaching!

After that it was Troy Town Secondary School in Rochester where I t

Dorothy and I had lived in a long succession of places by the time we bought our first house in Rainham in Kent. Bec

Things improved a bit down in Kent but we also had some dispiriting experiences there — such as trying to find accommodation with a new baby while I was teaching at Sheerness Tech. We had to move 12 times bec

I had a bit of luck in that our back garden, in Rainham where we had bought our first house, backed on to where the divisional director of education, Dorothy Howard, lived, and she was a very great help to me.

At the time

When I t

One day Dorothy Howard broached the subject of my becoming the head of

While I was at Halstead getting my teaching experience with special-school kids I met Howard Jones, who I later described to Dorothy Howard as 'a number one bloke'. Very good, very kind, very knowledgeable'. That's when they were appointing the head for

I was at

At that time I thought of Bower Grove as no more than any another special school, and to be honest I just wanted to be the head of a special school and beat all the other applicants to the job. However, by the time I left 17 years later I had no reservations at all about describing it as the best special school in the world. It was in fact regarded as the benchmark for special schools in Britain.

I have been fortunate through my life to have had many good friends but, perhaps not surprisingly, some of the more enduring friendships have been with people who have shared my interest in physical challenge and adventure.

My best friend was Harry Curtis; he was a PE teacher at another school in the area and we met through Inter-school sporting activities. He and his wife, Vi (always called Auntie Vi by Harry but I know not why!) were delightful people and we (Dorothy and I) had many outings together, including travelling and camping inFrance and Germany.

My other good friend, Ray Madden, who I met when I was teaching at Troytown died aged 31 and his death saddened me greatly.

Right: Harry Curtis, Eva Jagger, Dorothy, Vi Curtis, Joe Jagger.

One of the more notable perhaps was Joe Jagger, Mick's father. I first met him when I played in the basketball team he organised in Gillingham, long before the Rolling Stones became famous. Joe was the leader of the Central Council for Physical Recreation and he used to organise a lot of activities around the county. Once Joe asked me to take the v

Harry and I regularly helped Joe out on Saturdays with the rock climbing he organised for local kids at Groombridge, which meant sometimes took Mick climbing. One day he didn't have a rope, so I gave him mine and let him and his friend go off climbing on their own, which I probably shouldn't have really. Mick didn't stand out as anything exceptional in the early days, however, he was more impetuous than his brother Chris and, I think, later gave up a degree at the University of London to play with the Rolling Stones. I remember when we were canoeing on the river Medway once he offered me an apple if I would let Harry Curtis paddle with him instead of me.

Joe had a party to celebrate his being in education for 50 years. It was quite a big event, a dinner and dance for about 200. Joe's family all came and I remember I danced with the be

The Best Special School in the World

I was the first head appointed to Bower Grove. By the time I arrived there my philosophy on education was reasonably well formed. Based on everything I had read and learned, I firmly believed the role of education was to prepare people for life; so they could live a fulfilling life. It wasn't just about getting a good job and earning money. And there I was at Bower Grove with the ideal opportunity to put that philosophy into practice.

A lot of the things we did were outdoors. I think there's some aphorism that says, 'Don't teach a lesson indoors if you can teach it outdoors'. For me the really exciting parts of the program were getting them out of the school and doing activities that normal schoolchildren wouldn't be able to do.

We did things like horse riding and we got some kayaks so they could go kayaking. We often used to say to the parents, 'If you get the chance, come down here and see them'. And when they came they were amazed. A lot of them could drive a car; just in the grounds. We had a dual-pedal car and they had different circuits. They didn't just move it forwards and backwards, they actually drove it around. That sort of thing would give them confidence; it made them feel more important.

There was an old oast house in the grounds (a building for drying hops to make beer), which we made into a garage. We used the top of the oast house as a store and then had animals in the garage. Those kids who were good got to look after the animals.

We had some kids doing work experience once a week and we also set up a workshop and formed a company called BC Assemblies. There was a big hut available from the Lands Department and I asked if we could have it. They brought it over and we made it into the workshop where the kids who had left Bower Grove but didn't have jobs worked assembling, amongst other things, Cindy dolls (a British version of Barby) and did packaging. It was treated like a proper job and we put a stamp on their insurance card, which in Britain was the thing you got then if you were employed.

It was extremely rewarding to see the difference things like that made. As part of learning, skills for life tried to get as many as possible to travel to and from school using public transport and we had a deal of success at that. But I had one or two big mistakes. With one girl, I got it fixed up that, okay, she knew exactly where she had to get off at the corner and she had to walk just down a street; it was only a little bit out of Maidstone. But she finished up in either Eastbourne or Hastings, miles away right down on the coast. Fortunately, the bus driver had to go back the same way, he was able to drop her off and she got home OK.

Right: Bower Grove School

The most amazing thing was that the parents were oblivious to all this. I remember her father saying in explanation of his d

There was another kid, Stuart Corner, who had Mosaic Syndrome, however, he could drive any vehicle straight away, including manoeuvring a combined harvester with a trailer in limited space. His family had a small farm on land leased from the Council. When the land was eventually turned into a country club the Council employed Stuart as a driver on the property. He also got a cottage and lived on his own which, boy, was pretty good. He is 55 now and, unfortunately, has just been invalided out of the job bec

The main difference between us and other special schools at the time was that the other schools were doing what their governors told them they should do. Their focus was on the traditional schooling: reading, writing and arithmetic, rather than getting out and about, feeling confident and capable. We of course did the traditional schoolwork, but there wasn't the same emphasis on it.

I always describe Bower Grove as ‘the best special school in the world' but I truly believe it was, based on what I had seen happening in other places such as the States and in Australia. In most places it was a case of, 'Special education? What's that?' I had spent a grace term in 1976 in Australia looking at special education here and it was virtually non-existent. They were trying to get all the kids with special needs into ordinary schools, which was terrible. We built up such a good reputation at Bower Grove that people from various places used to send teachers to come and see what was doing; we were the benchmark school in the UK. There were so many of them coming I had it all set up on a slide show presentation. I also did a presentation for the Open University. Later they came back to see how things had progressed and changed, so we did another one. Not all of them were capable of work but it was really about giving them the attitude that they could have a satisfying life even if they weren't in jobs. For instance, with the older class, they used to go out in the community to help the local people. They could give them little jobs to do like weeding gardens and such. It was a way they could feel they had something to contribute to the community. But I always remember receiving a letter once that said, Dear Mr Bragg, please can I not be helped this term. I must have a rest.'

We made sure everyone could use the telephone and we would also get them to go to a neighbouring town on their own, such as from Maidstone to Tunbridge Wells, where they would report to the police station to say they had got there and then make their own way back to the school. Oooh dear. Some of the times I would be waiting there in the dark for them to come back, thinking, ' What can I do?' bec

I was always scared stiff that next thing the phone would ring and it would either be bad news or it would be the parents saying, 'Where the hell is so and so.' But, amazingly, they never phoned up. Probably thought, 'Oh, it'll be okay. He knows what he's doing.' Meanwhile I was back there in the dark worrying.

We also had a club we set up at the school for the past students, which they then ran themselves with different activities. The idea was to give them somewhere to come to. A lot of other clubs would not be accepting of them but there weren't that many clubs kids of that age could get into anyway.

The most significant thing about Bower Grove during the first 16 years I was there was that we had no governors - it was effectively a partnership between the parents and me. There were some fantastic people involved such as Bob and June Corner, Stuart's parents, and Sid Welfare who relentlessly turned up to every event. Our annual fetes were famous, attracting thousands of people and famous personalities to open them, such as Mary Wilson, the then Prime Minister's wife and Lord Longford.

It was acknowledged that Bower Grove's parents and friends were very active and our collective efforts brought results. For instance, through their contacts they got the Variety Club of Great Britain to buy us a coach to move the kids around. Charlie Chester, an entertainer at the time, was the person who presented it. And a bit later on, when we were saying, 'Well it's a very nice coach but there are about 16 kids who have to use it', they changed it for a 16-seat diesel coach.

When I left Bower Grove I remember I tore the pages out of the punishment book where you had to record the punishments you had given. Apart from misdemeanours like boys going into the girls' lavatories, there weren't many occasions when I had to use the cane. I had been in schools where the cane was used every five minutes but it had never seemed to me to make much difference.

I can remember the last time I ever used it. This big fellow had been rude to one of the teachers or welfare assistants in the playground and got sent in. I said, 'Where do you want it, hand or backside?' He said, 'Hand.' actually pulled the punch but he said, 'Ooow, can't you hit me there' pointing to the fleshier part of the hand. I must have hit his fingers or something. As he went out of the room he made some rude remark like, 'She deserved it the %*@ ' so I chased him and he ran like anything out of the school. I had to get one of the other teachers to drive the car and bring him back. But that was the last time I used the cane. I chucked it after that.

I actually became very friendly with that fellow in the end. There was one occasion when he bought a tie for his uncle - I don't think he had a father - and I said, 'Oh you didn't buy me one' and straight away he said, 'Oh here have mine' - and he was the big tough one. He got a job later on an oil rig and when he got dumped off in Scotland the first place he rang was the school.

The time I spent at Bower Grove truly was the most satisfying period of my career by far. When it was known that I was leaving, 90 of our ex-pupils came back for the farewell and a lot of them hadn't been back since they left the school. It may sound funny, but when I think back over the highlights and the rewards, I have to say that one of the most exciting things for me in that time at Bower Grove was when I said to a particular student, 'Hey, what are you doing?' At first nobody believed this, but he had just come out of the toilet and he said, 'Sh*t meself'. They were in fact the first words he had ever spoken.

A Taste for the High Life

I wrote somewhere once that:

There's a little kick of satisfaction you can get from tackling a new place, a new crag, a new country and the adventure comes from accepting the challenge to step outside the comfort zone. It's a journey of self discovery where boundaries are removed and inner strength is realised Through adventure we can reach new personal heights and redefine our perceptions of what is possible.'

I started in a small way as a teenager back in Manchester and I was still climbing mountains in my seventies. For me climbing meant proving yourself, it meant travel and all sorts of other concomitants that went with it. You get hooked.

I was obviously interested from an early age bec

After that I joined his club, the Mountaineering Club of North Wales, which meant I could stay in their hut. The next step, then, was to gain the MLC (Mountain Leadership Certificate), an all-embracing course which included a medical section — at the end of it you had to witness an actual operation. I suppose that was to ensure you could handle the sort of situations you might encounter.

Sometime after we moved to Kent I used to climb at a place called Harrison's Rocks in Groombridge, which was looked after by Terry Tullis. (His wife, Julie, who used to help with our school kids when we took them to the Rocks on their Outdoor Day, was later killed on K2after reaching the summit.) I was also instrumental in setting up the Kent Teachers Mountain Activities Association - which was actually subsidised by the Kent Education Commitee. I had been to the Alps with a fellow who set up something similar in another country and I thought it was a good idea.

We had easily 50 members. We used to meet in the hall at Bower Grove and we filled the hall. We had a hut in North Wales where we would often go at the weekends and we went to Europe during all the school holidays. I have a photo of me, still with rope and helmet, smoking a big fag after leading a group of us from the K.T.M.A. on a climb to Wildspitz in the Australian Alps in 1970.

I led the Kent Arctic Norway Expedition, KANE. It was an expedition to the Loppa Peninsula in Norway, which was 300 miles north of theArctic circle.

The 25 expeditioners paid their share and numerous donations from schools and industries, profit on raffles, and articles to newspapers covered most of the expenditure but still to come was the printing of the 24 page report which would be sent to Patrons and many supporters to show that Kent, the furthest county from any mountains in the UK was showing the way to others what could be achieved. We also took two 6th form pupils, Andy and Caroline.

I was the medic, psychologist and dentist, having done an advanced first aid course run by a doctor who t

As Blake said "Great things are done when men and mountains meet. These are not done by jostling in the street".

E.M.M.A.

Three years later was EMMA. Expedition to Morocco Middle Atlas mountains.

25 members travelled to a remote area inMorocco where they studied mi specific aspects of the local terrain. This time we included geology and entomology. I was the deputy leader and medicine man. At one stage set up camp at Almis du Guigou. The first patient was an old Berber with a badly lacerated leg, full of splinters, filthy, suppurating and infection evidenced by swelling in the groin. After extracting the splinters from the dung-covered, ulcerated sores, shell dressings and neomycin cream were applied. Instructions about taking a four hourly course of ampicillin were imparted by mime and sign language and a little help from a boy who spoke Berber and some French. Three days later, the camp comedians shouted that the patient was returning, carrying his leg! Not true; indeed the leg had completely healed and looked better than all of the well-bitten, scratched legs of the expedition members. This success led to a daily surgery for headaches lack of sleep, sickness, a crushed thumb, severe trachoma, and a third degree burn on a baby's abdomen.

We had bought a stripped out library van from the KCC for £65 pounds and a Bedford coach from the RAF for £190 pounds, which we used on be expeditions. After KANE we put an ad in the paper asking £150 and £250 respectively. So after using them for thousands of miles of rugged terrain we managed to make a profit! Our sponsor

KANE, The Countess Gravina was, this time, a member of EMMA as the interpreter and wrote an article on bivouacs for the Report. Once again EMMA was given a grant of 1,500 from the KEC.

Two of the fellows who became regular climbing companions — Mel Jones and Bryan Bullen - were people met through the KTMA but we did a number of climbs independently of the group. They were both better climbers than I was, which meant they were generally the leaders and they took the risks.

Bec

We had been snowed in for days — six of us in one large tent outside Chamonix. Very boring, so Mel, the best climber in the group, decided to go off and do something in Switzerland. Not long after the snow stopped and Mt Blanc was declared open again. I thought 'Mmm, I'll have a go at this.' After all, it was the highest peak in Europe at that time, (until Europe's borders changed to include Mount Elbrus) but only two others, Sue and Derek Rowell, wanted to go.

We took a train around to the start, then up a narrow valley to the first hut. It was quite a long climb and there were two more huts to come. It also included a slightly arched glacier crossing. They ran over it, faster than me, but another fellow who was crossing a great big crevasse higher up lost his footing and came crashing down past us to his death. The three of us were badly shaken. It wasn't a very aspiring scene to witness at the start of a climb but we continued on.

From the top hut we got up at 2.30am and went out, putting our crampons on in the pitch dark. We climbed to the summit and took the photograph of us all hugging each other. But coming down was another big challenge bec

We descended a short way and then took off on a glacier, which I hoped would lead to a hut. There was a bit of dissension at this point - being so tired and trying to avoid crevasses led to a certain amount of stress — but fortunately the roof of a hut appeared and we headed for it. I remember getting letters from them afterwards, still astounded that we had managed to find it. They thought it would be a very different way but I was sure I'd read that the very edges were the worst part, so I kept more or less straight down until the hut came into sight and we cut off to it.

For me that climb was my most satisfying principally bec

In 1987 when I was on my way to Everest base camp I met a young man, Hagay, also on his way up. I've never had altitude sickness but I think prepared better than Hagay. Hagay had gone off ahead but waited for me. I was just going slowly but we partnered up bec

I bumped into Hagay again in a tea house at Lukla. He was feeling really ill. The girl had gone and he was just mooching about. I said to him "Listen, you've got to drink loads of water and here's some Aspirin and Diamox pills" bec

To get to Kathmandu you have to fly out of Lukla's little airfield. You have to book bec

In Kathmandu, when I was taking Hagay's gear back to the hire company, the was a tap on my shoulder. I turned to find it was Hagay! He said, "I'll take it now, it's just around the corner." Amazing! He'd apparently had the youthful cheek to go to a little plane, that had nothing to do with the others, and say "Any chance of a lift out"? The pilot said he couldn't take three, but one of the guys in the plane, who was a workman sent to repair the wheel on another plane, said it was so nice in Lukla that he would stay another day and gave Hagay his place.

I went to Israel in 1990 to stay with some of my sister-in-law's family, Harry Akka's sister, Doris and her husband. However, when I came through t arrivals door there was Hagay to pick me up! I had sent him a post card saying that I would be visiting Israel but no more than that. His sister worked for El Al airways and she watched for my name on the passenger lists. He drove miles to pick me up and took me back to where he lived in Jerusalem. I stayed with him several days and he showed me all over the city and also took me to the Dead Sea where I floated on top of the heavily salted water reading a newspaper. We also did a walk; well it started out as a walk but ended up being a climb up a mountain. At the end of my visit with Hagay he borrowed a car and drove me back to Tel Aviv where I went to stay with Doris and Harry, who I had originally arranged to stay with. The unplanned delay in my arrival had luckily suit them as they had a business function to attend, so it all worked out very well.

Some of my most challenging experiences climbing came after I retired and I was freelancing. Instead of going with a group I was soloing everything. I'd sometimes get c

There were many successful climbs, however. I did Kilimanjaro just before we came to Australia. You had to get into a group to do it and I had teamed up with Ena Stanes a friend from the KTMA, who still keeps in touch. She was 4 years older than me and not a good climber, but she was obviously very game.

Kilimanjaro is one of the most be

Ena didn't make it past the hut and the others only got to Gilman's Point where the guides said, ' Here we are. Sign the book.' But I knew there would be snow and ice on the top. So did an Italian in the group so we both said, 'No, we're going on.' None of the young guides would come so it was left to the older guide to come with us. We got photographs on the top and when we got down we were given different certificates to those who had only gone to Gilman's Point. That was February 1987 and I was 63. gave the old guide my thick stockings. He had none at all.

An interesting postscript to this story is that my friend Stanley Darke managed to find the Italian guy when he and his wife were on holiday in Venice. I knew he had been a waiter there and had told them what his name was, so they searched around and actually found him. Joy all round.

Not quite so successful were my exploits in New Zealand in 1988, during the year Dorothy and I spent in Australia for her job exchange. I was by myself going for the Copeland Pass, which is a route that you climb up in the Mt Cook area. I actually got blown off and finished up with a sprained ankle. Fortunately, I came across another guy, Bob Sampson, who wasn't very fit and couldn't keep up with his group, so we stuck together. As we came down we crossed one river but couldn't get across the next as it was swollen. We were stuck and night was falling. Unable to reach the next hut that we were booked into we had to sleep outside with almost no protection, only a 'bivvy bag'. We were wet and freezing cold and could hear a helicopter overhead that was searching for us but it was too misty and there was no visibility.

The following morning we decided to try and get across the river using a rope. I went first and picked out where all the big stones were. Eventually we made it and managed to get down to the road and Bob got a lift in a passing truck. I was trying to hitch a ride and, amazingly a police car stopped and gave me a lift. I'm sure that wouldn't happen in too many countries. Kiwis are very friendly and helpful people. Bob and I have remained friends ever since and he and his wife stayed with us in 2001.

Egerton - The Best Village in England

We moved to Egerton in 1978 and lived at number

I was very involved in village life. I was president of the Egerton Players, which I saw as a good way of getting into the action. I did a some acting, my main role was in a play called Gosforth's Fete, which actually turned out to be the start of an acting career.

I was also on the committee running the Egerton Fete and eventually became the chairman of the committee. The main driving forces were myself, Richard King and John Frazer. At our 60th wedding anniversary there was a message from Richard King, who recalled that the first time he met me we argued about where the bales of straw should go to make the arena. Richard was quite a strong personality and he always wanted to run things. I suppose we both did, so we had a few disagreements over the years. Richard's allocated job for our first fete was advertising and promotion. Apart from putting signs up around the place, he utilised his contacts at Southern Television where he worked, and we ended up with thousands of people turning up and all the produce stalls sold out in the first hour. The fetes were very successful. Richard and I have maintained a strong friendship over the years, both in England and Australia. He and his wife have visited us a few times plus I did the afore mentioned D Day trip with him.

Another job I took on in Egerton was as postman when one of the permanent postmen got bitten by a dog - we found out later it was his own dog - and I stood in for him. It was very amusing to find out from the other postman, Alan, that there was a light in the post office and he used to hold the letters up to the light and say, 'Oh see this, they've gone to Greece' and things like this.

Amazingly there were two posts a day which we did on bikes. He took the easy run and I had to do the hard one with the hill down to the farms. The people down there used to say, 'Come in. Tell us what's happening up the top of the village.'

I always described Egerton as the best village in England but it actually did earn the title Village of the Year in a competition.

It was a very attractive village with a population of about 700. One of the best things about Egerton was that it had what I'd say were a lot of intelligent people who improved it and created all sorts of activities. There was something happening nearly all the time. It had a fantastic fete and there was an annual fun run. They had indoor bowls in the village hall, which was also used for the dramatic society, and later on when they built the new village hall they set up a computer wing for anyone who wanted access to a computer to learn how to use one. There is a music festival each year and street parties - something happening nearly all the time.

Egerton is a one shop, one pub, one church village. The best way to see what it is like is to watch the TV series Darling Buds of May. H.E. Bates, who wrote the books, lived in the area, so they filmed it in Egerton and the surrounding villages. Life in many ways is still the same as is shown in the series. The farms are still small with only a few dairy cows, sheep and chickens, and there are 'pick your own strawberry farms where you leave the money in an honesty box.

The countryside undulates with a patchwork of fields and a web of narrow roads that have room for only one vehicle at a time. Tall hedgerows obscure not only oncoming traffic but also herds of sheep or cows being moved from one field to another; the rush of modern life grinds to the halt of a bygone era.

A vignette of Egerton would be seen on a short run we used to do. Up the hill, past the George and the shop, through the church yard and a wooden gate into a plum and apple orchard. Then on to the lane past Egerton House (where the Players once put on an excellent performance of A Mid Summer Night's Dream) Down Lark Hill, flanked by blackberry bushes and the pungent smell of wild garlic. Left, past the sand stone houses then over a timber stile into a field with a scattering of field mushrooms, a blanket of buttercups and, sometimes, a bull. On through the farm yard adjacent to a manor house with fine, early georgian windows and soon back into

Time for a New Challenge

Bower Grove had been going for 17 years when I left to become an inspector of special education for Kent County. That was certainly a wrench for me bec

The timing was right, bec

My job was to go around to schools, see what they were doing and write a report. I always used to say when they saw an inspector coming they'd be very unwelcoming. It would be a 'What do you want?' sort of attitude, but when I got the reputation that I was the only one who had come through the ranks and actually done it, they used to throw their doors wide open. And I used to say to them, 'I know what being a head is like; all the troubles you will have, bec

I can remember there was a very difficult head teacher who was always telling his staff off for not keeping the kids quiet and when one of his staff's wife was having a baby he wouldn't let him go home. I thought, `That's poor' so did quite a bit of work on him. I actually went to one of their staff meetings In the evening and said to the staff, 'I'm Harry. I want you to call me Harry and if you don't mind I'll call you by your first names.' So we started this but I remember he couldn't say Harry, he almost choked over the word.

Dorothy eventually wrote a letter to the deputy chief education officer, a nice young guy, who said, 'I cannot believe that he can have a load like that, I'll look into it'; which he did and found it was much, much more than any of the others and he got it cut down. By that stage I had been trying to manage the workload for about a year. I can imagine how it happened - people in offices making decisions who thought, 'Well, we haven't got anybody looking after this, here's a new guy, put him in.'

I became good friends with a fellow school inspector, Stanley Darke. Stanley was the first person who came to see me when I became an inspector. He said, “I'm Stanley Darke and I believe you are a bit of a climber.' He had been doing quite a bit of mountain walking and said he wouldn't mind trying rock climbing.

I introduced him to Harrison's Rocks and he went crazy about them. He would often phone up after work and say, 'Where are you now? Come and we'll just nip down to the rocks.' I remember saying to him, 'You'll never be able to climb as well as I can. You're too awkward. Too tall', but in the end he did become a better climber. He did some very, very severe climbs.

I also introduced Stanley to running. In fact his son stayed with us here once and he said if his father hadn't met me he would probably have stayed in the house all day doing crosswords or something. He saw that all of a sudden his father was off climbing, running and doing

I had always run for fitness but I started doing longer distances after I gave up smoking in 1976 and later I got Stanley involved. We used to run together bec

The first one was a half-marathon in Norwich. Stanley then suggested we do a Masters and Maidens half-marathon in Gravesend but I thought, 'Memories aren't made of that! We can do better. Let's go to

There was one advantage to the hectic life as an Inspector. Inspectors could take leave whenever they wanted and not have to wait for the school holidays. So Stanley and I took two weeks off and ran in the New York Marathon in October 1980. It was my first marathon. I was 57.

We ran for the Home Farm Trust who sponsored our run in aid of

We ran six more marathons after that, including the in

By the time I retired as an inspector in 1984 I was still overworked, going to bed at midnight and so on. I had planned to retire at 60 but they asked me to stay on for a bit, and then between '84 and '87 I was going back doing a bit of part-time work. I gave up altogether when Dorothy got a work exchange to come to Australia in 1987

After that it was a long program of rehabilitation. One part of the rehab was that he had to go into Maidstone to do a cookery course, which meant having to catch the train so I started giving him a lift in a little old van I had at the time. I would sit outside while he did his cookery course, but then the next course was an all-day affair and it happened to be half price for oldies so I went with him onthat one.

It was a bit of a change of pace after all the more adventurous things we had done together - Stanley and I doing cooking classes together, but I really enjoyed it. I was also able to help by carrying things bec

Moving Down Under

Impressions of Australia: meat trays, mates, Singo, jonesy, arvo, sporting teams with animal names, beer guts, walk shorts, thongs, boatie shoes, hats, clean-ups, beaches, rock pools, the bush, clubs, RSLs, half serves, pokies, surfer, sea planes, spiders, utes, skinks, bindis, magpies, clean-up week, food in rest

What, then, made us decide to leave the 'best village in England', up sticks and move to the other side of the world? Well, as happy as we were in Egerton, we felt a very strong pull to be closer to the kids. It was obvious they had made their lives in Australia and they weren't going to be coming back so it seemed to me to be right for us to move so we could be a family again. There was also, for me, the sense of a whole new world waiting to be explored.

By then of course we were quite familiar with life in Australia so it wasn't a step into the great unknown. I had spent the grace term here in 1976, then we moved here for a year in 1987-88 when Dorothy got a work exchange, swapping jobs with an Australian counterpart who went to Eger and lived in our house for a year.

If anyone had suggested to me back in 1976 that I move to Australia I couldn't have countenanced it bec

That was fine until this big white bloke comes out, looks at him and says, ' Hey you! Get out.' I kept talking with the guy through the window but the bus driver started the engine and I said, 'Quick. Get in.' He tried to move off but the guy just got in in time. It was a repeat performance at airport. The Aboriginal guy was behind me in the queue and a little English guy that was full of his own importance said, ' Hey you, back of queue.' That was terrible. He was educated and friendly and better dressed than I was. That interaction turned me off completely.

I was obviously very happy to get back to England, judging by the notes I made describing the contrast between the two countries. I wrote:

The UK. • Land of Hope and Glory, Rule Britannia, Jerusalem, Last Night at the Proms, the village, the village fete, cricket, plays, runner beans (Mmm... Lovely), upper class, the BBC, WI, hills and downs. But then turn over and / have written the negatives- the weather, narrow roads with parking both 38 sides = virtually one way, too many cars, the M25, and expensive compared with Australia.

I think my impressions of Australia softened quite a bit after living here in '87/88 and getting to know more people. It also helped that for that year we lived in a wonderful flat in Mosman overlooking the Heads. By the time we moved in 1990 I could accept it warts and all, but I also think the warts had got smaller. In '76 it was awful the way they treated indigenous people but it had changed quite a bit.

When we emigrated we rented at first — back in Mosman - while we looked around for a place to buy. Unfortunately we then made a big mistake buying a brand new, very nice unit on Pacific Pde in Dee Why. I said it had to be south facing, which is the aspect you are always looking for in England, but here north facing is the thing so we never saw the sun. We persevered there for a couple of years before we sold it and moved to a townhouse in

When we lived in Dee Why I heard that a group of people was trying to start a Northern Beaches branch of the National Seniors Association, so I went along to the steering committee meetings at a church hall in Dee Why. I'm not sure why I got involved, but having just emigrated to Australia I was into anything new and, being 66, I was definitely a senior.

After much arguing and differences of opinion the Northern Beaches branch of the National Seniors Association came into being. It was decided, under John Treffry's chairmanship, that everybody on the committee should have a job; mine was assistant to Pat McNeil, the activities organiser. Pat resigned, so I became the Activities Officer, which was right up my street.

I took advice from my counterpart at the Dee Why RSL club, Lisle Shore; made good relationships with the Manly Bus Company and got down to drawing up a comprehensive programme of social activities such as: boat trips to the Sydney Fish Markets and Dangar Island; lunches at catering colleges and Rest

The bus company provided tea and coffee on the trips so, on one trip we made scones with a recipe that my d

I didn't put myself forward for the job but, when John Traffy resigned from being President, everyone wanted me to take it on. I was President a number of times over the years. The last time I was asked to do it I took the position on reluctantly. The Club was in a parlous state and I was influenced to accept by Ken and Anne Pare, two stalwart members who said they would be treasurer and secretary. During that year we reignited things by a number of actions. The venue for our meetings was changed, not only eliminated the stairs for those less agile but also the fees. We contacted members who had stopped coming and reinstated the newsletter. I organised the activities I knew were popular and included some even though they only attracted a few members as I felt we should appeal to broad spectrum of interests. Ensuring we always had interesting speakers at the meetings made a difference as well. My acting connections enabled me to get Bunny Brooke from the soap E Street to speak, and the

I remained in the position until October 2004 when I tendered my resignation. However, I agreed to take an ex-officio position of consultant.

Dorothy and I made many friends in the National Seniors. In fact, Dorothy has done a number of cruises with Gwen Jack. However, the saddest thing for me was in February 2006 when Anne Pare died. She actually wrote a letter to the Club before she died which I read out at the following meeting; very sad. She was a delightful woman and I valued the friendship of Ken and Anne Pare greatly.

An entertainer, Dorothy, Harry, Anne and Ken Pare.

I no longer attend any meetings of the Association due to my balance problem and recent fracture of my neck! But through Dorothy, I am able to keep in touch.

We travelled quite a bit throughout Australia once we were living here. We visited all states and territories and I well and truly ‘did’ Ayres Rock having not only climbed up it but also ran around it, and again when it was called Uluru.

Yet Another New Career

Perhaps it will make my acting activities clearer if I describe how they started. I emigrated to Australiaarriving on the 6th April 1990. Having got the taste for acting with the Egerton players, I thought I might try my hand at some work as an extra. My d

Over the years I have had numerous parts, too many to remember in fact: Babe in the City; Better than Sex; Praise; The Sum of Us; The Pact. (Movies) All Saints; E Street; Blue Water High; Home & Away; Water Rats; Murder Call. (TV shows) CBA; Milo; WA Lotto; Yalumba; Drive Washing Powder; Boost Mobile; Boeing (Advertisments) plus more.

I have enjoyed all the acting jobs I have done bec

The Boeing advert was the number one. It was filmed in the Rocks in an area made to look like somewhere in the USA. We had to go to some studios, south of Sydney and all the other actors, or extras, had to go by bus but not me. "Get Harry a taxi". And, finally, the pay; $3,584.44 for 6 months' showing and as they decided to show it for a further 6 months they had to pay again. Lucky for me, the rate of exchange had altered and this time the cheque was $4,217.50. Imagine $8,303.38 for one short day!

The Lotto ad was a good one also. It was for a $25,000 prize and I had to fly to Perth to do it. I walked into a deli, a barber's and then a newsagent's and said "just the usual thanks". I go into the newsagent's saying "just the usual thanks M

The "Boost Mobile" ad was me and another old bloke on skateboards and I had to say the catch phrase "Boost Mobile; where you at?' It led to loads of voice-overs and went to all the English-speaking countries and radio stations for at least a couple of years.

When they needed me, Tory, who worked for Boost, would send a taxi to my home and give me a cab-charge to get back. My grandson, Jamison, was with his friends comparing their phone's ring tones. When one of his friends played his, Jamison exclaimed "That's Grandad!" Boost had used my voice saying "answer the phone, answer the phone" as their ring tone. Finally, Tory sent me a new Nokia mobile which, of course, has my voice shouting 'where you at?' and 'answer the phone' etc. as the various alert tones.

Then there was "Praise" the film of the book which, sensibly, I bought and read. It was full of swear words and sex. I was first at the casting and told the casting agent I'd read it and she asked me to stay on to brief others as they came to

More Travel Experiences

I have always indulged my love of climbing but I really branched out in my 'get up and go' style adventuring after I retired. I made sure there would be adventures by stepping off the tourist routes and getting into unfamiliar places. I decided on a mission - to climb the highest point in each country I visited. Then the adventure could come whether one got to the top or just tried. This took me to many 'tops'. The highest was Kilimanjaro at 1895m and in Tuvalu the highest point was reputed to be a rubbish dump of about 3m, so I climbed that.

One of my more memorable adventures along the way was being arrested in the Philippines. I set out tanning to climb Mt Apo in the south island but, on the bus heading to the starting point, I struck up a conversation with a woman who happened to work at the local police station and told her what I was planning to do. When we got off the bus I set off but she obviously alerted the police who rushed up and said, 'No, you can't do it.' Apparently there were Muslim rebels trying to take over parts of the south island and they were afraid I might have been taken hostage. They then gave the woman the day off so she could take me around to all these interesting places and keep me out of trouble.

The good thing about coming to Australia was that it opened up a whole new part of the world to me and took full advantage of it. InIndonesia I climbed a mountain called Marapi and another called Mt Bromo.

The following year I went with Mel Jones to Mexico, Bolivia and Peru. The Lonely Planet guide stated that only paranoia would prevent one having gear stolen; which happened pretty well straight away. On the first night in Peru were walking to find accommodation and some street guys tried to get Mel's rucksack. Mel took off with them chasing him and it was only that someone came out of a doorway lighting up the street that they ran off. Next, when we were going into the train station, one big guy blocked the doorway while his mate tried to slash the pockets of Mel's rucksack open with a razor blade. Managing to keep his rucksack intact we continued on to the platform. Somebody with no shoes on was walking towards Mel. By now paranoia had set in and, regardless of this person's intentions, Mel proceeded to stamp on him with a heavily booted foot.

We hoped to climb El Misti. Actually, we made a bit of a mess of Misti. We didn't realise how far nor how difficult it was and we hadn't carried enough water. We did make it down to a tap but we couldn't turn it on, until I produced a 'Supa' tool, which did a variety of things, including turning taps on! Mel has never forgotten that.

We visited the Atacama Desert, at the north end of Chile together. This is the driest place in the world with only 2 centimetre of rain a year. Bec

Another climb I'll always remember is M

Luckily he had come up by car so we did get back to Hilo.

Recent Times

On my 80th birthday I had a surprise birthday party. I thought Dorothy and I were going to meet the family for dinner at the Hyatt Hotel, which is just next to the Harbour Bridge. When we arrived, there was the Jerry Bailey, a very nice 20 metre charter boat alongside an adjacent wharf. Peter Ewan, the owner had very generously lent us.

There aren't many couples that manage to achieve 60 years of marriage and, consequently, it prompts official messages of congratulations. Apart from many messages from friends we received messages from: our local Member; the Premier of NSW; the opposition leader; the Governor of NSW; the Prime Minister; the Governor General and Elyzabeh R herself! Again, we celebrated with a party on a boat. Plus we had a weekend at the Anchorage, Port Stephens where Bob Byrne, another friend took us on his boat.

Last Christmas the whole family went on a cruise to New Zealand. Although both Dorothy and I have been to New Zealand before the rest of the family hadn't, and it was the first time we had been away anywhere all together.

Most recently, for my 90th birthday my d

Harry hosts a high tea.

The Senior's group at Warriwood's Nelson Heather centre meet every Wednesday to sing their favourite songs from the 40s, 50s and 60s. The group is run by Pam Oxborrow who accompanies singers and duets on the piano.

Harry Bragg, became a 'groupy' to The Echoes, entertainers who performed at his 90th birthday. He visits the Centre to see them and listen to the other performers. As Harry doesn't sing himself he contributed last Wednesday by treating everyone to a high tea. The tea was served with all the finery of vintage tea sets, tiered cake plates and lace table cloths by members of Pittwater Community Gardens.

Harry Bragg at Avalon Tattoo June, 2014 - picture by A J Guesdon.

Copyright Harry Bragg, 2014.