January 30 - February 6, 2016: Issue 249

Finding God’s Own Country in Kerala

by Huang Zhi-Wei aka Reg Wong

Do you remember a time, here in Sydney, when there were at least two priests to every church? Or are you too young? There was the parish priest, usually first-generation Irish, and his assistant, the curate. For the larger than average parishes, there were two curates. Wait, that’s not all! The parishes also afforded a live-in house-keeper who cooked every meal and served morning and afternoon teas.

Honest, those were “the good old days” before the early 1960s when more than a few (typically Irish) families still retained the traditional practice of offering a son to study for the priesthood or the (de la Salle, Marist or Christian) brotherhood and a daughter to be a nun. When I lived in Neutral Bay, I was befriended by an immigrant Irish family who did just that. As a gracious thanks-giving, they returned to God half of their blessings of four children. They reciprocated God’s kindness by giving their eldest son and daughter to the religious life while retaining the two youngest ones for the secular life. Today, such an act of generosity would make the front page of The Catholic Weekly and make reverberating echoes that reach Rome.

Can you also recall a time when the teachers in our Church-run schools (St Pius X, for example, where I spent nine months studying for the school leaving certificate; or, its next door neighbour, Our Lady of Dolours, now Mercy College, in Chatswood) were predominantly strict disciplinarian brothers and sisters? Today, I lament the fact that brothers and nuns in our schools are a rarity. I pray the current situation is not an irreversible trend.

Not so in Kerala. They have a surplus of priests and nuns – and the numbers are increasing! As evidence, note the number of 12 current missionary Keralan priests enlisted by Bishop Emeritus David Walker to “fill the gap” in our own Broken Bay Diocese. “I would like to have brought out some nuns if I had somewhere to house them,” he said to me when I recently attended his lessons on the Imitation of Christ.

The Pieta outside many new Keralan churches

Kerala is a state in the south-west tip of the strawberry-shaped Indian sub-continent whose shores are lapped by the waves of the Arabian Sea. I visited the place, in March last year, to placate my curiosity. Why is there no shortage of vocations there? Aren’t the people Indians - and therefore traditionally and ritually Hindu? So why is there such an unwavering presence of hard-core Christians in the midst of a population dominated by Hindus and Muslims?

As the 21st largest state in India, Kerala has a population of 34 million, with 56% Hindus, 24% Muslims (descendants of Arabs) and 19% Christians. The remainder 1% is made up of Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains and Jews (who came in 70 AD, the year the Romans levelled Jerusalem and destroyed The Temple). Truly the most literate state in India, Kerala boasts a literacy rate of 91% but, among the Catholics, the rate rises to 94%. Curious about the reason?

Today’s run-of-the-mill Keralan Church

Of the 6.5 million Christians in Kerala, 60%, or just fewer than 4 million, are in full communion with the Bishop of Rome. These Syro-Malabar Catholics trace the origin of their faith to the evangelistic activity of St (Doubting) Thomas who came to Kerala in 52 AD. When Vasco Da Gama landed in 1498, he was surprised to find established Christian communities. Later, waves of Europeans came in quick succession. The Dutch (1603), the French (1667) and lastly the British (1794) brought their own missionaries who converted more of the local population to bolster the ranks of The St Thomas Christians.

The Presbytery and Parish Office

In the West, including Australia, we don’t wear our religion “on our sleeve”. We are reluctant and reticent - even afraid - to proclaim our faith. In Kerala, the St Thomas Catholics proudly announce and display their gift. St Faustina’s iconic picture of The Devine Mercy of Jesus is placed over the entrance of every Catholic home and every Catholic shop front. Pictures of The Holy Family adorn every home’s focal point, their altar, around which the family gathers for evening prayers. Before the first sod of soil was turned over for the foundations of my Keralan guide’s new house, his parish priest blessed the ground in front of a gathering of friends and neighbours. “Our faith is an integral part of our lives,” he explained.

Years ago we celebrated the Feast of Corpus Christi with crowds that over-flowed the grounds of St Patrick’s in Manly. Today the feast has been relegated to a low-level parish celebration and remembered only by those who involuntarily indulge in nostalgia. In Kerala, saints’ feast days take on as much importance as we place on Easter and Christmas here in Australia. I visited a place called Chalakudi at a time which coincided with the Feast Day of St Sebastian, the patron of the parish church. The celebration continued for four days and nights! Whole streets in town and villages were festooned with lights; there were mile-long candle-light processions; the town was choked with traffic; worshippers unable to find seats in the decorated churches contended themselves by milling in the streets; and pilgrims from the remotest part of town emerged to take part. Visualise ANZAC Day, the Mardi Gras, Royal Easter Show and a royal visit all rolled into one celebration and you will get an approximation of the atmosphere. When the feast was all over, there was a four-day retreat, attended by 15,000 people. I guess the sins from excesses of food consumed and coconut toddies imbibed during the festival had to be expiated. How practical!

Keralan Taxi called “Gift of God”

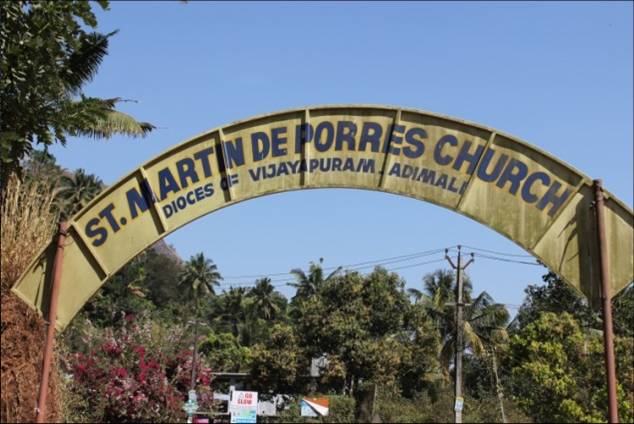

After inspecting another one of many churches, I looked for a taxi and found one named “Gift of God”. As I toured one small town I saw a bus simply called “Jesus”. Churches are ubiquitous – much like pubs in Ireland. Popular names are St Thomas, obviously, St Mary, St Sebastian, and even one for St Martin de Porres (my own church in Davidson). But by far the most popular is St Little Flower (actually St Therese of Lisieux) which lends its name to nunneries, seminaries, schools, and hospitals. As I travelled I grew weary of my own voice which announced repeatedly, “Look at that church! Look, there is another one!” By comparison with the Keralan churches, our Sydney suburban churches are simple “near-enough” functional structures. The tourist to Kerala is struck with wonderment at the sheer size, ornate design, and polish and finish – the huge columns, the extensive lead-glass windows, and the vast expanses of Rajastan marble floorings - of the new-generation churches. And, do remember, I haven’t mentioned the palatial presbyteries…yet…or the pilgrims’ retreats! Understandably the question pursed on the incredulous tourist’s lips is, “What is the source of funds to build these replicas of Solomon’s Temple? Surely not the locals – they are, by our standards, poorer than the proverbial church mice.” Western missionary societies, perhaps?

The ancient churches I have seen in England, Ireland, Wales and Greece are magnificent relics of a bygone era. To behold the giant basilicas characteristic of American capitals made me gasp at the ingenuity of man. But these Western churches were all financed by affluent people unrestrained by money issues. Check out The Heinz Cathedral in the grounds of Pittsburgh University to get an idea of what I mean. Today these Western churches are more like museums for tourists : that is, they no longer serve the original purpose for which they were intended, as houses of worship. In contrast, the cathedral- or basilica-size edifices in Kerala are built by monetarily-deprived – but faith-filled worshippers. It seems that their praise of God is only constrained by the boundaries of their imagination. And these churches are not for show and display but used, daily, by worshippers whose numbers are many multiples of our best Christmas counts. As an example, let’s look at the “Liturgical Schedule” at Our Lady of Dolours in Thrissur. It lists for an “Ordinary Day” the following rigorous schedule: morning (6.00 AM) and evening (6.00 PM) prayers, three masses and three novenas, and rosary and benediction finishing at 8.00 PM; for any Friday there are morning and evening prayers, six novenas, five masses, blessing of couples, blessing of the sick, benediction, “Mathapatha” (a local ritual), guided adoration of the Eucharist, and candle procession; and for Sunday, there are morning prayers, six masses (one in English) and one benediction. Then there are Patron Saints’ Festival days when the worshippers are even more numerous than on the days mentioned above. These activities weld the faithful together into one big cohesive family – and “the family that prays together stays together”.

When a plot of land is acquired to build a church, there are three construction phases. Phase #1 is the building of the elaborate house of worship – for the entire congregation; phase #2 is the construction of a mandatory primary and a complementary secondary school - for the needs of children of the parish (this explains why Keralan Christians have literacy rates which exceed those of any other religious group in India); and phase #3 is the laying down of a cemetery for the needs of those who depart this earthly life. No wonder the people of a parish identify strongly with their church: it caters to them from cradle to the grave.

St Martin de Porres Church in Kerala

Besides immersion in the spiritual realm, the faithful are also actively involved in the secular. Thrissur, “the cultural capital of Kerala”, is a hot bed of Catholic consciousness and activity. For example, in the 2011 national assembly elections, the Vicar General of the Archdiocese vehemently demanded the UDF (United Democratic Front) field Catholic candidates in the five constituencies. “The UDF had no choice but to agree. The five constituencies are now dominated by Catholics. In this 500,000-strong city of Thrissur, the Catholic influence and presence is all-pervasive. The faithful owns medical colleges, engineering schools, hospitals, training colleges for nun-nurses and the Catholic Syrian Bank, the biggest and oldest of only three banks in Thrissur.

Fishing in Kerala

Hospitality was a hall-mark of early Christians. It seems this practice has lost none of its lustre and fervour with the Keralan faithful. Even though a total stranger, I was welcomed by every family into whose home I stepped foot. Even the subsistence rice farmer provided me with an obligatory hospitality meal. If I had left without partaking of his gracious generosity, I would have brought shame on him. I felt like the reconciled prodigal son in the embrace of these faith-filled people.

Will I go again to Kerala, God’s Own Country? If you must know, I am already planning another (very affordable) trip to coincide with their next spring. Interested to join me for a pilgrimage to Kerala and get our heart, mind and soul recharged with faith, hope, and love?