February 8 - 14, 2015: Issue 201

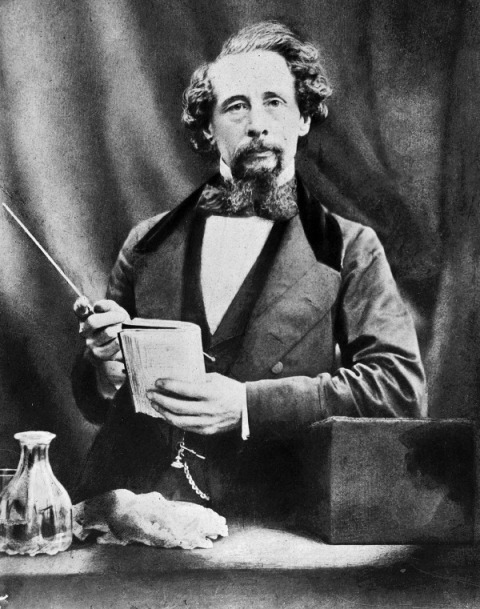

Mr Charles Dickens and his two Australian sons

The great English novelist Charles Dickens was born on February 7th in 1812. While looking around at what else occurred this week, and over 200 hundred years ago, we came across the unpublished poem below and found this esteemed writer, who championed the poor throughout his life, sent two of his sons, Alfred and Edward, here when they were quite young. Edward, arriving as a teenager, later became a Member of the Legislative Assembly in New South Wales.

AN UNPUBLISHED POEM ON CHARLES DICKENS.

BY THE REV. DR. E.H. BUGDEN.

In the sixth volume of the works of Voltaire, published in Dresden in 1748 by George Conrad Walther, which I acquired I know not when or where, I have found a number of poems written in pencil on the backs of the diagrams at the end of the book and on the fly-leaf. The book originally belonged to Peter Bohtling whose name stands on the fly-leaf with the date 1740. Subsequently it came into the possession of the writer of the poems, who scribbled the following epigram against the original owner's name :-

When Átropos her scissors brings,

With resignation let us greet her,

Peter was Bohtling all his life,

But in the end she bottled Peter.

The poems have the initial W.P.B., and they are dated between February and June, 1844. From the contents it is clear that W.P.B. was a physician practising in London at that time ; his first, name was William, and his lady was called Maria. With the help of Mr. Stanton Crouch, secretary of the British Medical Association, Mr. Colin McCullum, of the Public Library, and Dr. Charles Bage. I have identified him as William Perrin Brodribb, who practiced in Bloomsbury Square, of which he was one of the oldest inhabitants ; he died there suddenly in January, 1869. He held for many years the position of surgeon to the Magdalen Hospital, and he was secretary to the Court of Apothecaries. His father was Uriah Brodribb, of Warminster; and several members of a collateral branch of the family came out to Victoria, among them one who held an important post in the Education department.

Most of the poems are short epigrams, and they show that the author had no small gift of wit and humour ; but when Dickens published his "Christmas Carol" in December, 1843, Brodribb was moved to write the following appreciation of it, which I do not think has ever been printed ; and he appended to his poem a pencil sketch of the great novelists head, which is here reproduced :-

Here is the poem -

TO CHARLES DICKENS.

TO CHARLES DICKENS.We all would live upon the tongue of Fame,

And some, ambitious, seek the reins of State,

While others with the sword carve out a name,

Seek titles, wealth, broad lands, and honours great.

And some would strive to gain the changing crowd,

Bending the ignorant masses to their will

By faithless speeches, virulent and loud,

On fancied wrong or non existent ill,

And many gild their leaden natures o'er,

Plodding the dusty path of Gain, to save

The name of affluece, nor quit their store

But for the stillness of an unwept grave,

How greater is the noble Patriot's aim.

How nobler far the greatness of his soul

Who heeds no honours, asks no other fame

Than to attain the honourable goal

Of giving freedom to a fettered land.

But higher still than e'en the patriot's flight

Soars pure Philanthropy, and in her hand

She bears a banner, radiant with light,

Inscribed with Charity, Goodwill, and Peace,

Her angel pinions glitter in the sun

Like some good spirit's, new in his release,

Who deems not yet his earthly duty done,

Too cold the hearts of many for her throne,

Too little love * for a plant so rare,

But she has marked some bright ones for her own ;

Look in your breast, Charles Dickens, she is there.

Deem not this fulsome-I, who know you not,

Can have no cause to flatter. Is there one

His read your Christmas Carol, and forgot

To grant the praise your noble task has won?

If such there be, so heartless, dead, and cold

To kindly sympathy, may Heaven impart

A better knowledge of the home-truths told

By your bright genius and your Howad's heart.

Let kings and princes and the titled great

Glory in what their ancestors have done,

Don the insignia of Jewelled state,

The gewgaw badges that their birth has won ;

But Nature's true nobility will aye

Outlive these sons of Fortune ; in their breast,

Not on it, beams a star of heavenly ray,

A heart of love and sympathy's their crest ;

Their 'scutcheon shines with little ones at play

On fields of a gladness, ' or ' and "azure ' there

In golden plenty, on a summer day,

Filling the wrinkles in the brow of Care

No rampant, grinding dragons do we see

Of Avarice-no niggard wretches find,

But Pity soothing tearful Penury

With gentle hand casts sorrow to the wind.

Bright love and Sympathy support the shield,

Each holding by the hand a child of woe ;

Not clubs and swords, but olive slips they wield,

And heavenward guide the eves of those below ;

The motto-Charity. Well have you earned

Thus noble 'scutcheon, well have won your fame,

And even selfish heart this book has turned

Will call down blessings on your honoured name.

-Feb., 1844.* Word Illegible

AN UNPUBLISHED POEM ON CHARLES DICKENS. (1930, March 29). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), p. 7. Retrieved fromhttp://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article4078082

DICKENS SONS IN AUSTRALIA SOME INTERESTING REMINISCENCES. EXCITING ENCOUNTER with BLUE CAP, THE BUSHRANGER.

By Trevallyn Jones

It was my privilege to be closely associated with Alfred Tennyson (pictured right) and Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens, the two sons of Charles Dickens, the famous novelist, who left England for Australia in the '"sixties of last century. I met Alfred in Melbourne (Vic) in1865, and again in the seventies, when there was a gathering of bohemians at a famous club. It was Charles Dickens' birthday. The guest of honor was his son Alfred, and many friends and admirers of the popular author were among those seated round the old oak table. George Darrell, the actor author, proposed the sentiment, "To the memory of the author of the immortal Pickwick." Many interesting speeches were made, and some humorous stories of the popular author were related by his son, who was a capital raconteur.

It was my privilege to be closely associated with Alfred Tennyson (pictured right) and Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens, the two sons of Charles Dickens, the famous novelist, who left England for Australia in the '"sixties of last century. I met Alfred in Melbourne (Vic) in1865, and again in the seventies, when there was a gathering of bohemians at a famous club. It was Charles Dickens' birthday. The guest of honor was his son Alfred, and many friends and admirers of the popular author were among those seated round the old oak table. George Darrell, the actor author, proposed the sentiment, "To the memory of the author of the immortal Pickwick." Many interesting speeches were made, and some humorous stories of the popular author were related by his son, who was a capital raconteur. It was only natural that the advent of the sons of Charles Dickens-Edward arrived in 1868-whose novels had attained widespread popularity in Australia, should evoke considerable interest, and not a little curiosity, among the denizens of that far-flung; outpost of Empire. Possessed of a striking personality, and attired in the latest London fashion, Alfred was a conspicuous figure in Collins-street. He was quite the "lion of the hour," and a welcome guest at all functions.

Alfred was a passenger to Australia in the ill-fated London, and he had an exceptionally bad passage all the way. A terrific storm was encountered in the Bay of Biscay, which so alarmed the commander, Captain Gilmour, that he declared his conviction in the dining saloon that the London "would never reach Australia!" This so upset Lady M'Nabb, of New Zealand, that she retired to her berth and remained there all the way to Australia.

Alfred had letters of introduction to Mr. Murray Smith (in later years Agent-General in London for Victoria)and he gave that gentleman a graphic account of the perils of the voyage. Mr. Murray Smith wrote to friends in England who had booked for the next trip of the London to cancel their passages. It was fortunate that they accepted the advice, for the London, on the return journey, went down in the Bay of Biscay. Among the drowned were the celebrated tragedian, G. Brooke, and many other notables. In the middle 'sixties an acute reaction iinuning had set in in Victoria, and the colony was still suffering from the effects of "Black Thursday," the most devastating bushfire in the history of Australia. Consequently many avenues of employment were closed.

It was some time before Alfred became reconciled to his new environment. It was all so different to life in London. Like many other young- Englishmen, including the late Lord Salisbury, the lure of the goldfields attracted him, but the "gold fever" had died down, and he returned to Melbourne from Bendigo and Ballarat sadly disillusioned.. Through the good offices of Mr. Murray Smith, Alfred secured a position on a sheep-station at Spring-dale, in New South Wales, where he had many exciting experiences. Bushranging was rife in that State in the fifties and 'sixties, and Alfred's arrival at Springdale synchronised with the advent in the Narraburra Ranges-the favorite haunt of bushrangers-of the notorious Blue Cap gang, whose vicious deeds terrorised south-western New South Wales for years. Blue Cap had decided to "stick up" Springdale station - but the police, who were hot on his trail, informed the station overseer. In the middle of the night Alfred Dickens was called up and asked to assist in the capture of the desperado.

Alfred, in telling me the thrilling story, said:-"I was never so excited in my life, but when I was told to take up a position at a cross-road on the fringe of the dense and frowning forest, and to shoot the first man I saw coming out Of it, I was scared to death. The minutes seemed hours, and every moment I expected to be shot at. I shall never forget the relief I felt when I heard a stockwhip crack, and one of the station hands call out that Blue Cap and his blackfellow had been captured. They had been surprised sleeping by a fire." The next day young Dickens assisted the police in escorting the outlaws to Bahranald, on the Murray River, where they were tried and convicted.

The police magistrate, addressing Alfred, remarked: "Your courage and patriotism form a fine example for the young: men of this colony to follow." A rather funny incident occurred during the long journey to the court. Alfred's gun, which was an antiquated weapon, exploded and a bullet penetrated Blue Cap's saddle. In the court the outlaw, pointing to Alfred, said: "That young parson fellow deliberately tried to shoot me yesterday." With a twinkle in his eye Alfred told him that he very nearly shot himself, which was more likely. His station career was exciting enough, but it was not a great success.

He was an indifferent horseman, and knew nothing about the management or handling of stock.

His account of his efforts at riding buckjumpers was extremely amusing:-"At my first attempt I was sent whizzing through the air, and had to be carried to the station casualty-room suffering from a sprained ankle, and in my second essay I found myself sitting in the middle of a road with the saddle between my legs. But I succeeded in the end, for I mastered the worst outlaw on the station."'

He acquired considerable knowledge of accountancy, and his services were largely availed of by squatters and businesspeople. Eventually he became a financial agent in Melbourne, and had offices in the foyer of the Metropole Hotel in Bourke-street.

Chatting over a glass of wine in his office one day, Alfred declared that he made the mistake of his life in not accepting an offer which had been made to him to undertake a lecturing tour of the United States in the 'seventies,: and, he remarked, "I am sure my metier is the lecture hall!"

I am afraid he overestimated his ability. There was nothing magnetic about him, and he had very little of his father's talent. He was a frequent contributor to the press, but his ""copy" was often returned "with the editor's compliments." , I think it was about a quarter of a century ago when he decided to cross the Pacific and try his luck in the United States. I believe he died in one of the Western States a year or two afterwards. Australia was the poorer for his departure, he was generous to a fault, and always a friend to the poor.

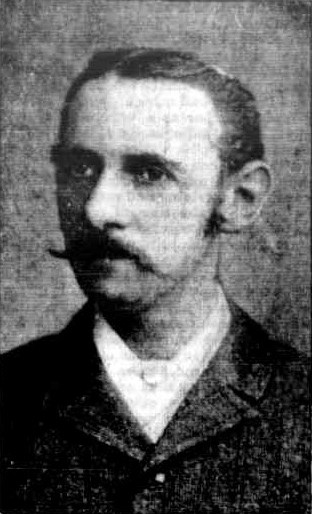

Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens.

Alert, active, and ambitious, and endowed with considerable ability, great things were expected of Edward("E.B.L.," as he was called), who was not a bit like his elder brother in appearance, disposition, or temperament. I think it was at the end of 1868 when he landed in Melbourne. Like his brother, he had difficulty in deciding upon a career. Though he often said,

“I care nothing for politics," he was induced to offer himself as a candidate for a seat in the Legislative Assembly of New South Wales, and he scored an easy victory. He was an ardent supporter of Sir Henry Parkes. At that time there were many sittings in the Legislative Assembly, and sometimes there were exciting scenes.

"E.B.L." was not a very frequent contributor to the debates, but he displayed a ready wit, and his clever interjections not infrequently upset an opponent.

On one occasion, when feeling ran high, and neither party could spare a supporter, so evenly were they divided, pillows and rugs were brought into the House, and the debate, which was about the inevitable fiscal question, dragged through the long hours of the night. Edward Dickens secured a rug and ensconced himself in a corner. His occasional snoring evoked uncomplimentary remarks from the Opposition. The motion to adjourn had been debated for hours, when a country member, tired out and disgusted, jumped to ' his feet, and said: "Mr. Speaker, why not end this farce? Let us adjourn and all have a drink'." A head emerged from under a rug in the comer, and the familiar voice rang out: "Mr. Speaker, Barkis is willin'"'*The House broke into uproarious laughter, and the motion was put and carried unanimously.

Edward was not happy in his early environment. He entered Parliament with the idea that he could better the condition of his fellow-colonists. The foundation of things had been laid, and he was anxious to play a part in fashioning the superstructure. He soon realised that the land laws called for amendment, and he was opposed to the Customs barriers on the borders. He formulated a policy based on liberal lines, but his party was opposed to it, and not long afterwards he retired from politics, and devoted his energies to pastoral pursuits, but not before he had directed attention to the potentialities of the River Murray for irrigation enterprises. On that subject his was "a voice crying in the wilderness," 'and he was described as a "dreamer.''

Today millions of money are being expended on irrigation in New South Wales to provide farms for thousands of British settlers.

Had Edward Dickens' advice been seriously considered there would not have been the tremendous losses of stock year after year for 40 years, and the "parent State" would have been much more advanced than she is today. It was a common saying when any of his neighbors were in trouble: "Go and see Mr. Dickens; he is better j than a lawyer." The settlers had unbounded faith in his wisdom, and evidence of his popularity exists to-day in the form of an inscription, cut in big letters on a gum tree, near his old home: "Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens, the settlers' friend."

I have a vivid recollection of a visit he and I paid to a station a hundred miles from his own. Edward required more stock, and we went to inspect a flock of merinoes. It was tea time when we arrived, and, Edward was given a very cordial welcome. During the evening the little twelve-year-old daughter of our host brought out her library, which consisted mostly of Dickens's novels. She astonished us later

by reciting the Christmas Carol so charmingly and effectively that it brought tears to Edward's eyes, and he took the little lady on his knee, thanked her, and told her to "cultivate her wonderful talent." "When we drove away the next day we found a wreath in the vehicle. It was composed of wattle blossom, and on a card attached to it were these words: "Give my love to your father, and tell him I love Little Nell and the dear old schoolmaster."

She had not heard of Charles Dickens' death.

We past a shepherd, who told us he had read all Dickens' novels, and declared he could "recite every line of 'Little Dorrit' without reference to a rote." On the way home Edward became reminiscent, and related one or two interesting stories about his father and his school mates. "The pater," he said, "'hated horseplay, and when we wanted to annoy him we indulged in it. Alfred and I induced him to come with us on a boating excursion on the Thames one cold day. We nearly capsized the boat twice, and when the pater lost his temper and reproved us we splashed him with muddy water, and 'accidentally' knocked his hat off. When we reached land, he grabbed Alfred's hat, jumped out of the boat, and fled home."

The brothers were greatly disappointed when their father declined an offer of £10,000, made by a few colonial admirers, to visit Australia and give a series of readings. Alfred showed me his father's letter, in which he said: “I should like to come to Australia, it is a very tempting offer, but that vast expanse of sea and the many months the journey would occupy combine in impelling me to forgo the great pleasure of seeing you, and to decline the very generous offer of my friends in Victoria.'' CHARLES DICKENS' SONS IN AUSTRALIA. (1924, July 13).Sunday Times (Perth, WA : 1902 - 1954), p. 11. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article58055417

*: This story is untrue - The truth is that when he apologised to the speaker for an indiscretion, and explained that "sons of great men are not usually as great as their fathers", there were unkindly calls of "Hear! Hear!"

The Late Mr. E. B. L. Dickens. EX-M.L.A. FOR WILCANNIA.

YOUNGEST SON OF CHARLES DICKENS.

Mr. Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens died at the Criterion Hotel, Moree, on January 23, after along illness. He was the tenth child, and the seventh, last, and favorite son of Charles Dickens, and was born on March 13, 1852, the year in which "Bleak House" was written. He was named after his famous godfather. As a baby he was nicknamed "Plornishghenter," which was subsequently abbreviated to "Plornish" and to "Plorn."

Mr. Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens died at the Criterion Hotel, Moree, on January 23, after along illness. He was the tenth child, and the seventh, last, and favorite son of Charles Dickens, and was born on March 13, 1852, the year in which "Bleak House" was written. He was named after his famous godfather. As a baby he was nicknamed "Plornishghenter," which was subsequently abbreviated to "Plornish" and to "Plorn."In November, 1853, Dickens, writing to his sister in-law, Miss Hogarth, says : "The Plornishghenter is evidently the greatest, noblest, finest, cleverest, brightest, and most brilliant of boys. Your account of him is most delightful, and I hope to find another letter from you somewhere on the road, making me informed of his demeanor on your return. Give him a good many kisses from me. I am very anxious to see whether Plorn remembers me on my reappearance."

In September, 1855, he writes in a letter to Mrs. Watson: "I think of inserting an advertisement in the 'Times' offering to submit the Plornishghenter to public competition, and to receive £50,000 if such another boy cannot be found, and to pay £5 (my fortune) if he can." In 1863 he writes :"One of my boys (the youngest) now is at Wimbledon School. He is a docile, amiable boy, of fair abilities, but sensitive and shy." In 1868 we find it decided that he shall try New South Wales, to which place his brother Alfred had already gone. This parting was a great trial for Dickens—"Poor Plorn is gone to Australia. It was a hard parting at the last. He seemed to me to become once more my youngest and favorite little child as the day drew near, and I did not think I could have been so shaken." In his parting letter to his son he says, "I need not tell you that I love you dearly, and am very, very sorry in my heart to part with you. But this life is half made up of partings, and these pains must be borne. It is my comfort and my sincere conviction that you are going to try the life for which you are best fitted. I think its freedom and wildness more suited to you than any experiment in a study or office would have been; and without that training you could have followed no other suitable occupation. What you have always wanted until now has been a set, steady, constant purpose. I, therefore, exhort you to persevere in a thorough determination to do whatever you have to do as well as you can do it. I was not so old as you are now when I first had to win my food, and to do it out of this determination, and I have never slackened it since. Never take a mean advantage of anyone in any transaction, and never be hard upon people who are in your power." And, after advice about religious matters, he concludes, "I hope you will always, be able in after life to say you had a kind father. You cannot show your affection for him so well, or make him so happy, as by doing your duty." A letter to his son, Alfred Tennyson Dickens, shows his anxiety as to Plorn. "I am doubtful," he writes, "whether Plorn is taking to Australia. Can you find out his real mind? I notice that he always writes as if his present life were the be-all and end-all of his emigration, and as if I had no idea of you two becoming proprietors, and aspiring to the first positions in the colony, without casting off the old connection." This was his last letter to those sons. Before they received it, the news of his death was telegraphed.

Though Charles Dickens mentions Wimbledon School, most of the school life of Mr. E. B. L. Dickens was passed at Tunbridge Wells, in a private school conducted by the Rev. W. C. Sawyer, who was afterwards appointed Bishop of Armidale and Grafton out here, and met with a sad death, being drowned in the Clarence River. Before Mr. E. B. L. Dickens left for Australia he went through a course of lectures in the Royal Agricultural College, Cirencester, Gloucester-shire. Early in 1869 he went to the Darling, and obtained his colonial experience on Momba Station, in those days the property of E. S. Bonney and Company. He remained with that firm for many years ; and on their purchasing Mount Murchison he was appointed by Mr. Bonney as the manager of that station, where he remained till 1881. He had previously purchased a share in Yanda Station ; but owing to bad seasons and other causes, the venture was not very successful. After leaving Mount Murchison, Mr. Dickens resided in Wilcannia, where he carried on the business of a stock and station agent. In 1886-7 he was appointed Government Inspector of Runs in the Bourke district. At Wilcannia he took great interest in local matters ; was a member of the Municipal Council and the Licensing Board. He manifested a lively interest in Masonic affairs, and was W.M. of the Moorabin Lodge, Wilcannia. In 1889 he was elected M.L.A. for Wilcannia. In recent years he has been an inspector of C.Ps. In 1880 he married Constance, daughter of Mr. Alfred Desailly, who survives him. The Late Mr. E. B. L. Dickens. (1902, February 1). Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 - 1907), p. 26. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71519589

Picture from: Mr. E. B. L. Dickens, M.L.A. FOR WILCANNIA. POLITICAL. (1889, April 6). Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 - 1907), p. 13. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71117137