Yamma Ngunna Baaka - From the Northern Beaches to Bre: Our Sister City Shares its Water Woes

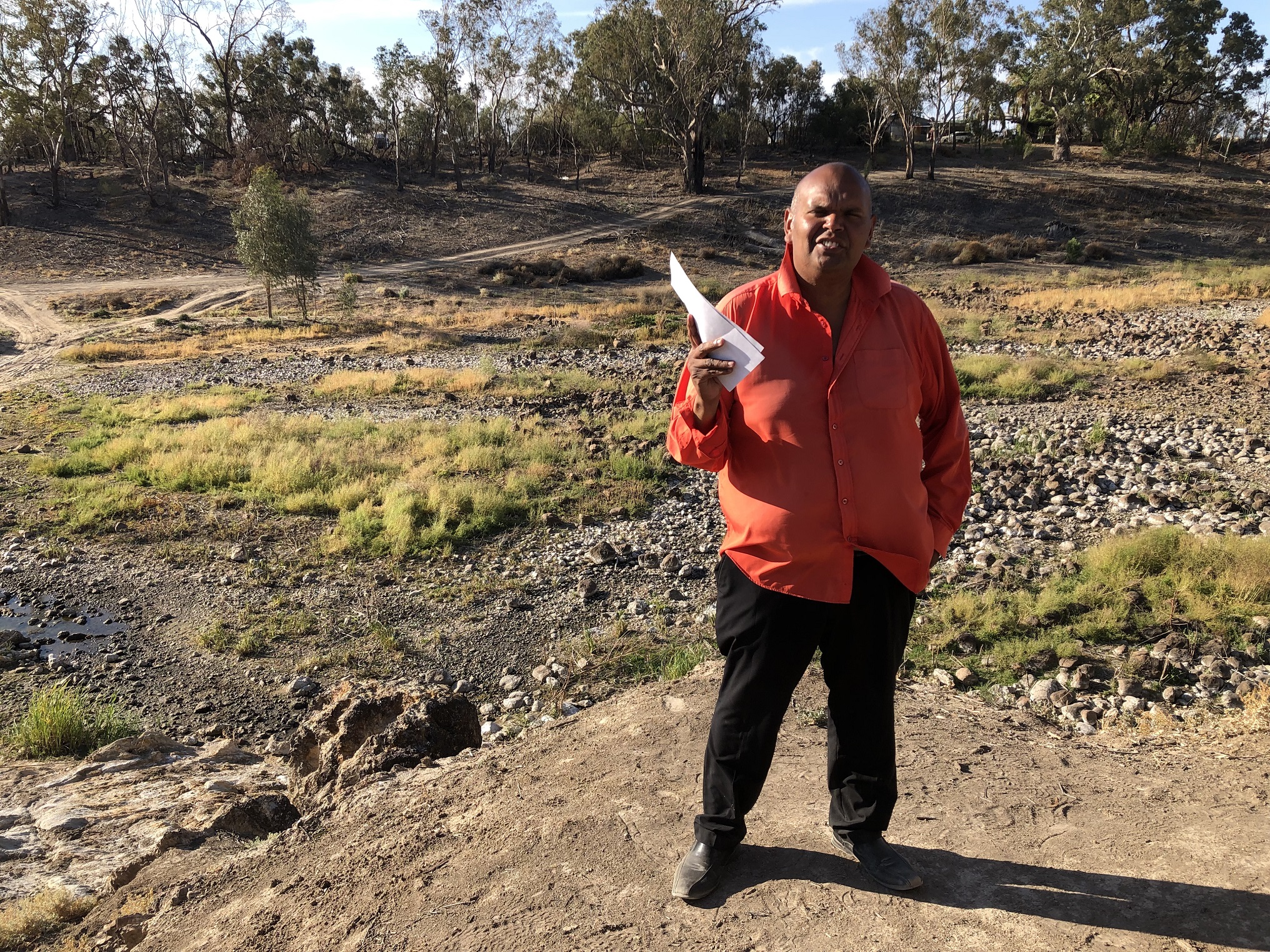

Barwon River at Bewarrina, October 2019

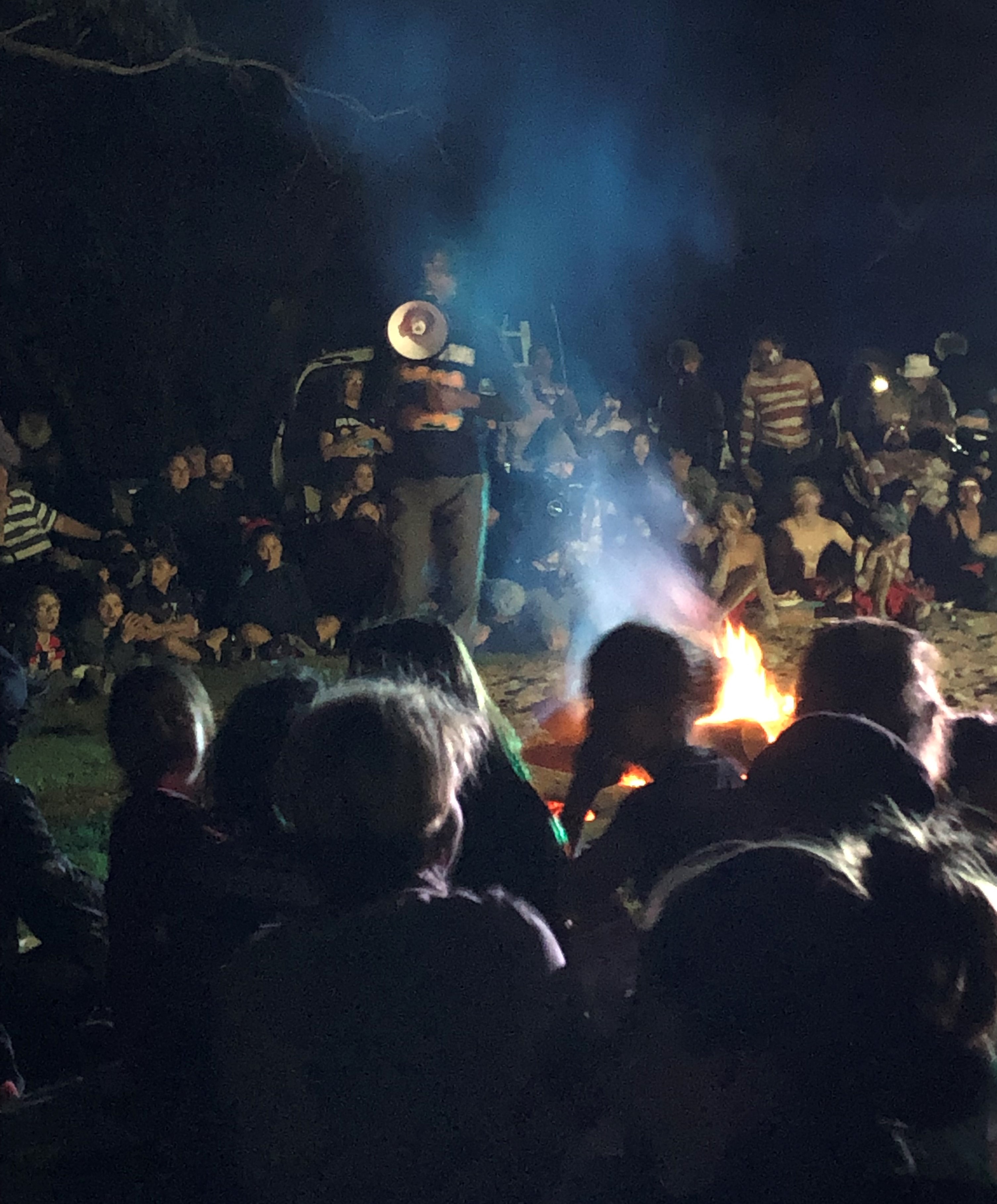

Gathering at dusk for corroboree in Bre

October 12, 2019

Uncle Bruce Shillingsworth stands in the firelight by the Barwon River at Brewarrina, telling us a story from the lower Baaka – the waterways making up the parched Murray Darling Basin. He promises our gathering, a corroboree with more than 300 spectators, that it will be one of the largest ever seen on the river.

People have been gathering all afternoon by the Barwon and as sunset turns the sky delicate shades of pink, apricot and blue, the festival feeds the hundreds of people assembled for the corroboree, the menu including emu and Johnny cakes. The event has the air of a gigantic family picnic, with Aboriginal grandmas on fold up chairs balancing toddlers on their laps, kids sitting or kicking dust beside two fires burning, and adults standing around the circular corroboree ground chatting.

“A couple of weeks ago I took my mother down the river in Bourke and we walked the river. The dry river bed,” Uncle Bruce begins telling the crowd.

“My mother is now in her 90s. She had never seen the river in this condition.

“In her lifetime, she’s lived on the river. She’s camped on the river, she’s fished those rivers.

“In the Darling River here, my children learnt to swim, my children learnt to fish. Now it’s disappeared.”

A Muruwari and Budjiti man, Uncle Bruce is so angry and determined to bring water back to the rivers that he’s organised a convoy of more than 200 people, travelling on two buses and in some 50 cars, to visit the lower Baaka. Reminiscent of the Freedom Rides of the ‘60s, the Yamma Ngunna Baaka Corroborree festival (otherwise known as Water For Rivers tour) departed from Sydney and has now reached Brewarrina (or Bre as the locals call it). Some 15 of us hail from the Northern Beaches, including members of our local Aboriginal Support Group and the Greens. Eight hundred kilometres from Sydney and with a population of 1,800 - 60 per cent of it Aboriginal - Bre is a sister city to the Northern Beaches.

Those in the convoy were invited by Bruce and the people of the Baaka to hear their stories and join their corroborees at towns along the way. Setting out in late September, we drove first to Walgett, then Bre, on to Bourke, Wilcannia and, finally, Menindee and its dessicated lakes on October 2. Most of us camped out in showgrounds, and by the river and lake beds. Some learned of the trip at the towns we passed through and joined in for a night or two.

In Bre, it’s in the high 30s when we arrive. The streets are hot and dusty like those of other country towns we’ve travelled through, with empty shops and a few indigenous people sitting in the shade of a tree in the park next to the river. The town is famous for a series of World Heritage Listed fish traps built 60,000 years ago by the local people. A guide at the Aboriginal Cultural Museum, Bradley Hardy, gives us a rundown on the traps and the modern Aboriginal history of Bre – which isn’t pretty.

Amongst his stories is an account of the Hospital Creek Massacre in 1859, 15km from Brewarrina, in which 400 Aboriginal men, women and children were rounded up and shot. No-one knows for sure what precipitated the event – but Bradley thinks the most likely story was that a white stockman went missing and the local indigenous people were blamed.

Aboriginal people's memorial to Hospital Creek massacre

He also shows us illustrations from the Brewarrina Mission, which operated from 1886 to 1966, and where around 25 Aboriginal languages were spoken by 1930. Indigenous people from Queensland, the Northern Territory, South Australia and Victoria had been forced to live on the mission’s six-acre block, Bradley tells us.

“They did that to our people – remove saltwater people, took them to the river, took our people to salt water - to make them lose that connection with their land, country, values, languages, traditions, lifestyles,” he says.

Bradley then brings us outside the museum perched above the river. It’s cut deep banks into the earth, in terraces, and on the top is a levee, some of it decorated with Aboriginal designs, to prevent flooding in Bre. It’s hard to imagine this happening with the current collection of muddy pools far below.

“On these flat banks on both sides of the river, these are the original banks where our people done all their corroborees, all their ceremonies, all their get-togethers, all their dances,“ he says.

“Now, our old people used to teach us about the landscape: we don’t own the land, we belong to it, we share it with each other. And the waterways, we belong to it, we share it with each other. We don’t own the fish traps, we belong to it, we share it with each other.

“So our duty as people is to keep all that talk alive, all the caring and sharing. What the government’s done is tricked our people into, ‘I own this, my tribe owns this, my tribe owns that’.”

The traps are made up of a series of U-shaped stone walls, along with ponds for storing live fish, but the local custodians always left a channel open allowing 60 to 70 per cent of fish to swim upstream to breed. Those swimming into the traps could be caught by hand. Bre has a weir but with water now failing to flow across the top of it, the traps form a series of shallow and disconnected pools. Fishing and swimming are no longer possible.

Bradley Hardy show us the 60,00 year-old fish traps in Bre

In the evening, as the air cools, the corroboree begins with a call for our ancestors to join us. The dances are a cry for rain - stamping the ground brings the attention of Mother Earth. The performers come not only from Bre but also from as far afield as Queensland, and the Coorong in South Australia. One song tells a story about the rainbow serpent travelling across the land and creating the rivers; others are about ordinary life - like gathering bunya nuts from the ground. Children are included and non-indigenous men invited to join the kangaroo dance, the audience in stitches when the kangaroos recline and scratch their bellies; all women are invited to participate in the emu dance –about families looking after each other. But the corroboree is a living thing, with new dances too, some swapped between brothers. Later in the evening, a young rapper, Dobby, who now lives in Sydney but who’s grandmother was born and raised in Bre, sings through a megaphone about “Better rivers in better states”.

Uncle Bruce Shillingsworth speaking at Bre corroboree

Dancing at Bre corroboree

The Aboriginal people are not the only ones concerned about the rivers in Bre. Local Mayor Phillip O’Connor – who was also born locally and owns a garage in the town – tells me that there’s no water in Burrendong, Keepit and Copeton Dams either.

“The problem is it’s all been allocated. The river system can’t handle the amount of water that’s been extracted from it,” he says in an interview.

“… Of course there’s a drought, but these rivers when we grew up here ran most of the time. Now they hardly ever run.”

The situation is undoubtedly complex, with the Barwon and Darling Rivers thirsty for water during the drought. But Brewarrina locals are angry that water is being stored in dams, holding thousands of megalitres for cotton farms in southern Queensland, destroying the natural flows of the Baaka.

The Mayor says the easiest solution is to sink a bore but in Bre there’s no bore water. The artesian basin starts 50km closer to the Queensland border and the quality of that water is deteriorating anyway. So the town is pumping the dregs from above the weir on the Barwon, which is “real salty now”.

“We have got no filtration,” Phil tells me.

“Your shirts when you wash them look like you’ve been sweating in them all day due to the salt.

“The water is treated in town but we can’t take the salt out of it.”

The NSW government had promised the town a small desalination plant that was meant to arrive six weeks ago – but the town is still waiting for it, he says.

The Mayor is very grateful to the residents of one shire however, who have trucked three semi-trailer loads of water to Bre.

“The people of Griffith just put their hand up and have been carting water in to help us for free,” Phil says.

“They even tried to offer fuel for the truck. It’s unbelievable.”

Brewarrina Shire Councils Mayor Phillip O’Connor

Back in Sydney Pittwater Ward Councillor Ian White explains that the Northern Beaches Council already supports a youth exchange for young people between here and Bre each year, scholarships to help its young people study in towns like Dubbo, and advice for a family support program being set up for girls in Bre.

“We have done more in the past. We need to re-invigorate the link,” Ian says.

“They’re dealing with such major problems.”

He does some investigation after I talk to him about Bre’s water problems and says he would be happy to consider help with an infrastructure proposal and support a council motion on returning water to the Darling River system.

Another Pittwater councillor, Alex McTaggart, is also prepared to vote on a motion focused on returning water to the rivers. However, our third Pittwater Councillor Kylie Ferguson declines to comment on how the Northern Beaches could help our country kindred.

However, the problems are not restricted to Bre but affect communities right along the Baaka, illustrated devastingly by fish kills earlier this year. We camp by Lake Pamamaroo at Menindee and see dead emus on the bottom of the dry basin. Along with kangaroos, they are used to finding water in the Menindee Lakes when all else dries up, so are going there and expiring around their edges.

Fruit growing, such as the seedless Menindee grapes along with stone fruit and mangoes, has collapsed, and we see withered vines on the way to Menindee.

Uncle Bruce tells us at Wilcannia a couple of days later about the issues salty and polluted water from both bores and the rivers are causing, such as exacerbating kidney problems, giving kids sores and depression leading to suicide.

“The drying up of our rivers is affecting our First Nations people so severe that our people are now starting to suffer health problems,” he says.

In fact, they fear that the lack of clean water is a deliberate strategy to drive the local people from their traditional lands, leaving the water purely for irrigation.

“It’s a form of genocide. It’s a modern-day genocide,” he says.

“They want to kill off the river towns and they want to kill off our First Nations people that live along the river.”

Instead, Uncle Bruce says governments needs to start fixing the rivers and demands the politicians listen to the locals.

“We demand that we have the right to clean water,” he tells a media conference in Wilcannia.

“We, our First Nation people, don’t want to leave our land because we are connected to our environment: our waterways; our rivers; our totems; the things that give us life - the natural water cycle - and help us to survive in our environment …

“We’re going to say: we’re going to make you accountable. We want a Royal Commission into the Murray Darling Basin and all our rivers right across Australia.”

The water doesn’t belong to the big corporates or the Australian Government, he says.

Instead, like Bradley at the museum and so many other local people, Uncle Bruce tells us:

“That water belongs to the public, it belongs to First Nations people. It belongs to nature, it belongs to mother Earth.

“The rivers feed the land and give life to our environment.”

by Miranda Korzy

Convenor,

Northern Beaches Greens

Levee above the Barwon at Bre

Background

Brewarrina Sister City

A Sister Cities agreement between Brewarrina Shire and Warringah councils was signed in July 2000. Brewarrina, or ‘Bre’ as it is known to locals, is a remote community located in north-west NSW, 800kms from Sydney, and has 1800 residents. It has a large Indigenous population, is home to the World Heritage listed Fish Traps and has a wonderful history.

The idea of the relationship is to promote friendship between beach and bush communities and allow a greater understanding of the issues facing each area. The Councils agreed that one way to achieve this is by a youth exchange, where young people would be able to meet, form friendships and learn about each other's lives and communities. The agreement is still in place with the exchange taking place in April 2019.

Brewarrina Council chambers

Bush to Beach Program

Each year South Narrabeen Surf Club hosts children and carers from the Brewarrina and surrounding districts at the club. On January 17th 2019 30 plus Children and 8 carers from Brewarrina, Bourke and Goodooga assembled at the Brewarrina Youth Centre for a trip to Sydney’s Northern Beaches, under the watchful/caring eyes of Danielle Boney, Youth Team Leader Brewarrina Shire Council and all the carers.

South Narrabeen Surf Club was the destination (about a 12-hour bus trip) where the kids and carers were to experience; the beach, waves, great food, new experiences, learn basic first aid, CPR, meet new friends as well as enjoy a great educational experience, all part of the annual Bush to Beach program (which started in 2006).

Pittwater supporters in Beryl Driver OAM, that Palm Beach Mermaid who has often made the journey to Brewarinna outside of Variety B to B Bashes, and Neil Evers, Aboriginal Support Group of Manly-Warringah-Pittwater, are often on hand to greet the youngsters.

Friday morning the bus arrived at South Narrabeen Surf Club, lots of excitement, smiles and G'days, A briefing for all the visitors on Water Safety, Surf Conditions, where to swim, Stranger Danger and a whole lot more.

Mayor of Brewarrina Phillip O’Connor arrived in time to watch the kids enter the surf and to enjoy the great lunch provided by the Manly CWA Ladies (and their scones). We were very pleased that Phillip and Jeff made the effort to attend Bush to Beach, great blokes who love their town and community.

After lunch they were again taught water safety and to learn to ride surf boards, (thanks to Manly Surf School), the kids were amazing with most standing on a surf board in a very short time, back to the surf club, fish and chips for dinner,

Lunch at Narrabeen Lakes Primary School, as well as classes in basket making and painting, the kids played basketball, soccer, It's great seeing all the kids having a great time, again, last Summer.

Visit Pittwater Online's 2019 report: Far North West NSW Aboriginal Kids’ Cool Change With First Ever Beach Visit

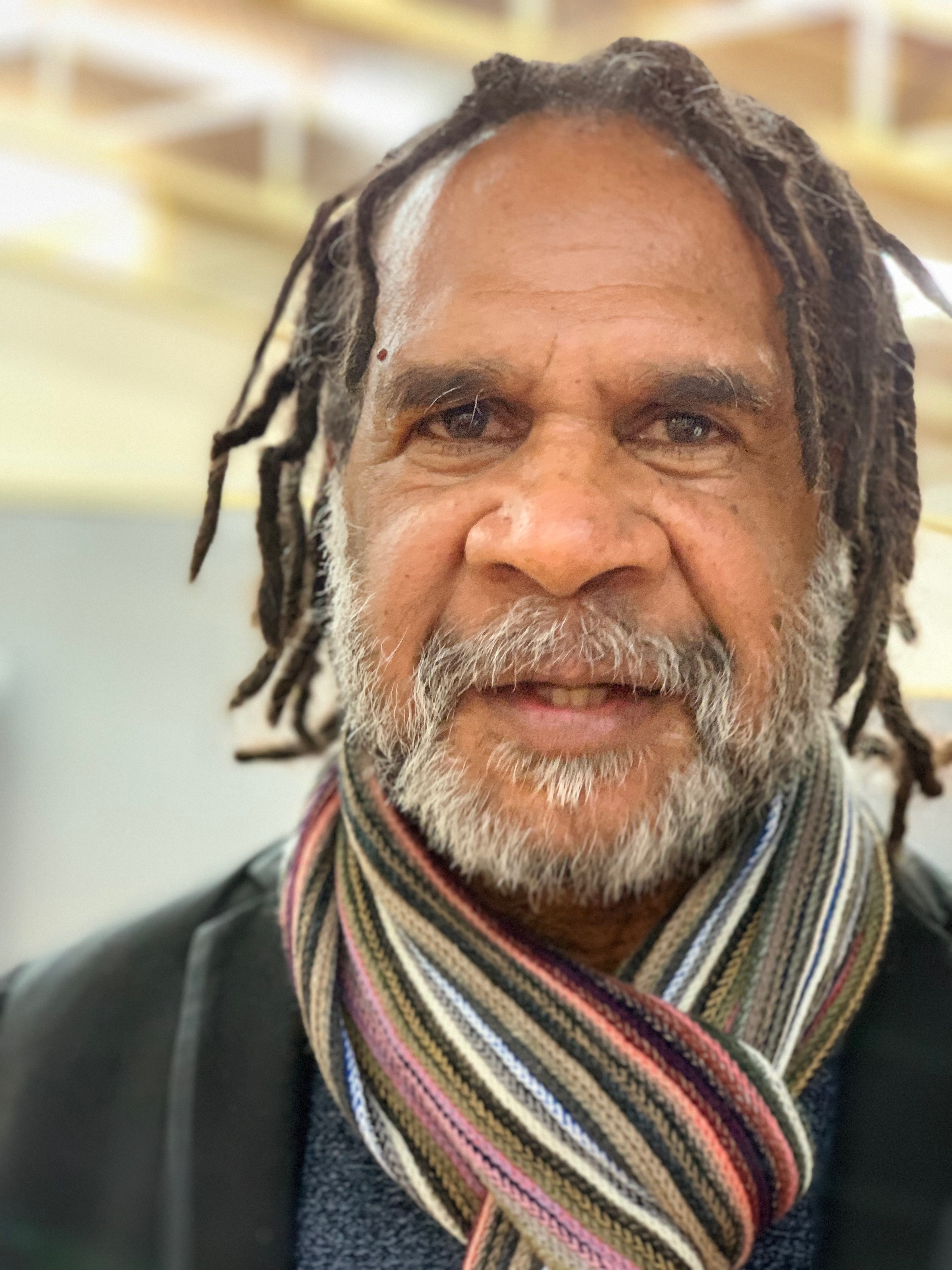

Bruce Shillingsworth at ASGMWP Meeting at Mona Vale, September 2019 - photo by Mandy Mullen