May 10 - 16, 2020: Issue 449

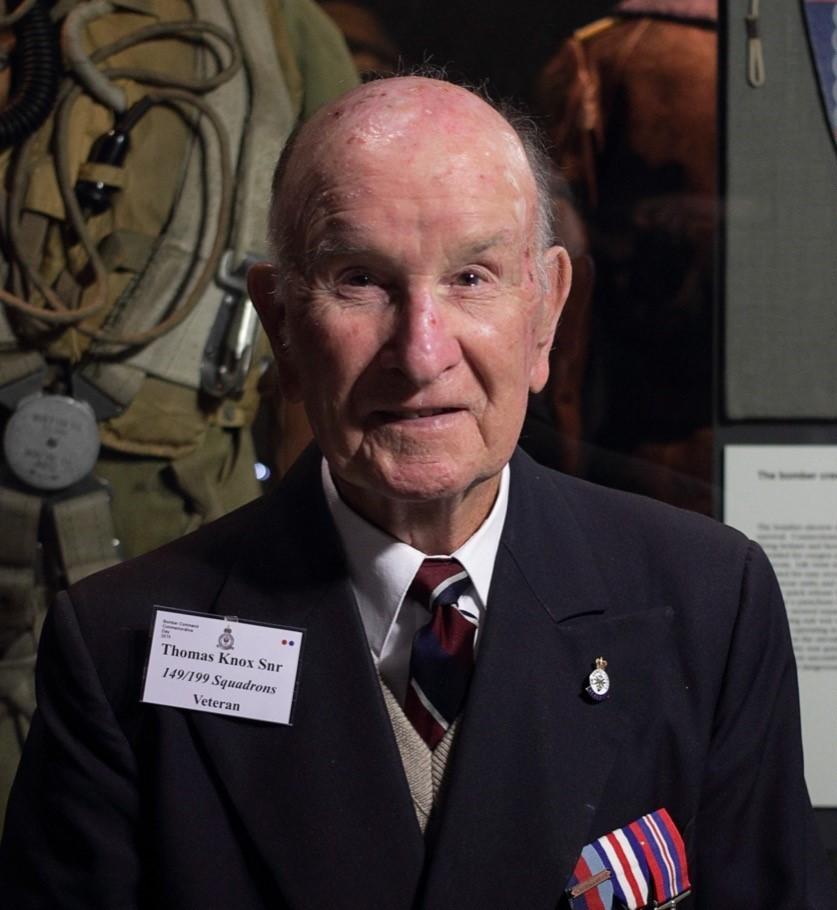

Tommy Knox

The 8th of May is VE Day, Victory in Europe Day, the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Nazi Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, May 8th 1945, marking the end of World War II in Europe and marked each year with services commemorating those who gave their lives. In 2020 it is 75 years since the guns fell silent at the end of the war in Europe. The years of carnage and destruction had come to an end and millions of people took to the streets to celebrate peace, mourn lost loved ones and to hope for the future.

They were not forgetting those still in conflict until August 15th, when it was announced that Japan had surrendered unconditionally, effectively ending World War II, and remembering that the 8th of May 2020 also marks, for Australians, the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Wewak in New Guinea, where 442 Australians were killed and 1,141 wounded in that last campaign of the 6th Division.

But after six years of darkness, our UK and USA cousins, with many Australians alongside them, could exhale for moments, dance in the newly returned light.

At 9.00pm on 8 May 1945, King George VI made a radio broadcast to his people; -

Today we give thanks to Almighty God for a great deliverance. Speaking from our Empire’s oldest capital city, war-battered but never for one moment daunted or dismayed – speaking from London, I ask you to join with me in that act of thanksgiving. Germany, the enemy who drove all Europe into war, has been finally overcome. In the Far East we have yet to deal with the Japanese, a determined and cruel foe. To this we shall turn with the utmost resolve and with all our resources. But at this hour, when the dreadful shadow of war has passed from our hearths and homes in these islands, we may at last make one pause for thanksgiving and then turn our thoughts to the tasks all over the world which peace in Europe brings with it.

Together we shall all face the future with stern resolve and prove that our reserves of will-power and vitality are inexhaustible.

Piccadilly Square pictured as supporters celebrate VE Day, May 08, 1945. Photo taken by Sgt. James A. Spence, during his service in World War II.

At dawn, alike here on Anzac Day 2020, buglers and trumpeters took to their streets up and down the UK to sound out the Last Post. This year the Last Post was piped over the internet, services conducted online and the sound of the March through the streets muffled by the need, in the UK, to protect that nations' citizens from a pandemic. The silence made the Remembrance and Tributes more powerful, marked in starker form how so many individuals strove alone and as one for one purpose.

The Royal British Legion, a British charity for veterans of the British Armed Forces, their families and dependants, organised VE Day 75, a three-day international celebration to take place from May 8th to May 10th 2020.

We will remember the members of the Armed Forces and Merchant Navy from many countries who gave their lives or returned home injured in body and mind, the hard-working women and men who operated the factories, mines, shipyards and farms, and ARP wardens, police officers, doctors, nurses, fireman, local defence volunteers and others who toiled day and night selflessly on the home front during difficult frightening and uncertain times.

They called on people across the UK to join in a moment of reflection and Remembrance at 11am on Friday May 8th, the 75th Anniversary of VE Day, and pause for a Two Minute Silence.

On Anzac Day 2020 Mona Vale hosted a very special parade as 95 year old World War II Royal Air Force Veteran Thomas Knox travelled on his motorised scooter along his home street at 11am so neighbours and relatives could wave and salute this Pittwater RSL Sub-Branch 'Living Treasure'. Tommy would have been among the VE Day celebrations in 1945. Two of his crew members were Australians Hugh Coventry and David Skewe, and they may have had an extra beer that day too.

This week we hear about Tommys' war service and why he came to Australia in 1950.

You were born February 9, 1925 in Scotland – whereabouts in Scotland?

Glasgow – I left Glasgow in 1950 when I came to Australia. I had a wonderful childhood growing up there. We lived on the perimeter of the city at a place called 'Carnwadric', surrounded by wheat fields and greenery and dairy farms, it was great.

You enlisted in the Royal Air Force in 1943 at 18 years of age?

Yes, I was in a Reserve occupation, I was an apprentice with the railways. The only thing that could get you out of a reserve occupation was to volunteer for Air Crew. The opportunity came when I was 17 and a quarter years to apply. So I went to the office in Edinburgh and did all the tests and was placed at the back of the pack. I got called up just after my 18th birthday. I trained as a flight engineer at 4 School of Technical training in South Wales.

1943 - Tommy Knox, Staff sergeant 170th Glasgow Company Boys Brigade 1st Pollockshaws.

What were you flying?

I only flew in Stirlings. The engineer’s job was very different in Stirlings to that of those flying in Lancasters and Halifaxes, and you had to specialise in one or the other and I specialised in Stirlings. This turned out to be very fortunate for me as we were taken off main targets while we were in the squadron; they were losing too many Stirlings, Stirlings couldn’t get the high altitude and the Lancasters would unintentionally drop bombs on top of us. So they put us on Special Duties, which was great.

Our first operation was on 31 March 1944, mining Frisian Islands, subsequent ops included bombing, more mining and low level moonlit trips to supply the French Resistance fighters.

What were you dropping to the French?

Cannisters with ammunition and arms – anything that they needed we were dropping.

It was very exciting. You used to go out by yourself, on moonlit nights, doing low flying, we would run in at about 200 feet and drop these supplies away in the middle of France somewhere. The navigators did a great job finding the fields where the resistance fighters were.

Did you always want to fly, to be in the planes?

Oh yes. That was the main reason to try and get into the Air Force, to fly.

You transferred then?

Yes, I joined up with a Unit called the ‘Heavy Conversion Unit’ (1657 Conversion Unit) at Stradishall, Suffolk. – they had been flying Wellingtons. This is a twin engine bomber and they were converting onto the four engine bomber Stirling. And that’s where the Engineer joined the crew.

The crew consisted of two Australians, two Canadians, two English and me. We moved to 149 Squadron at Lakenheath, Suffolk on March 15th 1944 and stayed there until the squadron converted onto Lancasters and we were transferred onto 199 Squadron, which was still flying Stirlings.

1944 Squadron 199 - Tommy Knox photo

That’s where we finished our Service, there. We did our last op on November 11th 1944, having completed a tour of 40 trips. The crew split up.

You did Diversionary Raids over Germany – what is a 'diversionary raid'?

We would take on a Wireless Operator with a huge wireless setup with which to jam the Germans’ radar – so he would operate that. We’d fly to the target and he’d use his wireless setup so the Germans couldn’t pinpoint the bombers.

So we didn’t drop any bombs we just orbited sending out these signals the whole time, and then would head back to base camp.

Were you ever frightened?

Not really, just excited. I wasn’t brave or anything, it was just what we did, especially on the Special Duties runs where we were doing the low level flying, it was great fun. You don’t get any impression of speed when you’re up high but when you’re down low you feel like you’re going 500 miles an hour.

Tommy in 1944 - all dressed up with somewhere to go - RAF North Creake

You received the Legion of Honour medal, from France?

That was for our contribution to D-Day on the 6th of June – we were flying over France flying supplies to the Maqis (French Resistance Fighters) when the invasion was talking place. I got the medal on behalf of the crew because everyone else is dead, they’re all gone now. I’m the only one left. It’s not because I did anything special, because I didn’t, it was on behalf of the crew, who all played their part.

Tommy Knox - Receiving medal from the French Consulate in September 2015. Photo by Michael Mannington.

We were sent over on the 6th of June. We came in over France at low level to find the drop zone, I recall flying low over the paddock, and we were instructed to avoid any airfields because they were all occupied by the Germans. We had to look for three lights in a row and another light flashing a Morse letter - and that was the beginning of the “bombing” (supply canisters) run – that’s why we flew very low because they were actually map reading to find the paddock where we would drop the supplies.

After we had finished our 40 operations, the crew was split up.

You were then posted to 30 M.U. at Sealand, Cheshire as a Draughtsman?

To keep us occupied after flying I was sent to a Maintenance Unit as a Draughtsman. The war finished while I was there. While there I kept going up to look at the board and saw one day they were looking for people to be parachute jumping instructors. I thought ‘that would be good, I could get back to flying again’.

I put my name down for that and finished up as a jumping Instructor. PTIS course, I did my first jump from a balloon in February 1946 at Manchester and finished up training paratroopers in Palestine.

1946 parachute Westons on the Green before a balloon descent

You were sent to Palestine?

Yes, there were problems there and the British were trying to sort it out, but they gave us a lot of trouble. We were more or less confined to the camp – you couldn’t go anywhere by yourself, there had to be at least two of you together.

I demobilised on February 23rd 1947 in Palestine. I sailed back from Alexandria and was demobilised.

I went home to Glasgow and then decided to move to Australia – I’d been flying with Australians and it sounded good to me. The first job I got when I got back to Glasgow was shovelling snow away from front doors and so you can understand how attractive Australia would have seemed.

Who were the Australians you were flying with?

The Skipper Hugh Coventry, he was born in Melbourne, his father Syd and Uncle Gordon were famous in AFL, go the Magpies! and living in Clermont Queensland when he went home, and Dave Skewes who was the Wireless Operator was from Perth in Western Australia.

You came out to Australia in 1950, were you on the ten pound pom program?

Yes, I was a ten pound pom. I sailed to Brisbane to get as far away from the U.K. as I could.

.jpg?timestamp=1588892593060)

SS Mooltan - Tommy departed London on the SS Mooltan June 9th 1950 - arrived in Brisbane July 29th,1950. Photo shows the Mooltan being assisted by the tug Carlock at Brisbane, photo courtesy John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

My Skipper Hugh was running a pub northwest of Brisbane at Clermont, I met his wife when I landed in Brisbane, she was down there doing some business for the pub. We flew up and I stayed in the pub for a couple of weeks and then went back to Brisbane to work. I was marking off steel for machinists for a firm doing metal windows. I then went on to Rheems and did maintenance there. That’s also where I met my wife, Ros Taylor.

Ros was a Sydney girl who was travelling through hitchhiking around Australia with a pal. After she left Brisbane she went back to Sydney. I missed her a lot so I followed her down – and that’s where I met my Waterloo so to speak. We were married at Walker Street North Sydney in 1952.

Wedding Day of Tommy and Ros

The happy Bride and Groom

What did you do for work after moving to Sydney?

I worked for the Shell Oil Company at Pyrmont where I was servicing their petrol pumps, the kerbside ones.

So you’re happy you came to Australia then?

Oh yes.

The solo Parade on ANZAC Day this year along your street in Mona Vale was very special – did you enjoy doing that?

I used to be able to do a proper March, but not anymore. Last year I did it in a wheelchair.

Tommy Knox Passing Twinami family in Mona Vale, Anzac Day 2020 - photo by Michael Mannington

At Trafalgar Park Cenotaph, Newport

Your granddaughters organised this year’s March – how many grandchildren do you have?

Thirteen – 10 girls and 3 boys, and 2 great grandchildren. I have helped to repopulate the place.

What’s the best part about living in Mona Vale for you?

Number one would be the family is all around me here, my three daughters and my son, they have been a tremendous help as I get older. They all visit me regularly to do various things and I’m very well looked after.

I also have very good neighbours who pay regular visits and do all sorts of things for me. My wife died about 11 or 12 years ago now and I’ve been well looked after ever since.

Tommy with his son Tom, photo by Michael Mannington, Anzac Day 2020

What is your ‘motto for life’ or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

The main thing and the simplest thing I would say is moderation in everything, that’s what my wife would say; don’t do too much, don’t eat too much – just moderation in everything.

Tell the truth, and if you make a promise, keep it.

Notes And References

A flight engineer wore a single-winged aircrew brevet (actually a flying badge - the use of the word “Brevet” actually describes a certificate in French) with a wreath containing the letter 'E' on his tunic, above his left breast pocket denoting his trade specialisation. During the initial operational service of four-engined bombers second pilots were carried until sufficient flight engineers had been trained.

The introduction of heavy bombers with four engines brought the necessity of engine management and a new trade entered service with these aircraft. A "Flight engineer" was chosen specifically for mechanical aptitude. The flight engineer sat beside the pilot and assisted him particularly at takeoff, during the flight monitoring the engines and vitally the fuel efficiency, pumping fuel between the tanks as required. It was not unusual for these airmen to be a little older than their colleagues and often had prior mechanical experience. The flight engineer was usually a sergeant; promotion was very slow indeed.

No. 199 Squadron RAF

No. 199 Squadron was formed at Rochford on 1 June 1917 with Royal Aircraft Factory BE.2e biplanes to teach pilots advanced bomber training. Renumbered as No. 99 (Depot Training) Squadron RFC the squadron moved to RFCS Harpswell, Lincolnshire in 1918, as a night bomber training unit, where it was disbanded on 13 June 1919.

The squadron reformed at RAF Blyton on 7 November 1942 equipped with the Vickers Wellington, after a few months the squadron moved to RAF Lakenheath and was re-equipped with the Short Stirling heavy-bomber. Between February 1943 and June 1943 the squadron was based at RAF Ingham in Lincolnshire training for maritime mine laying over The Wash. Following training the squadron returned to RAF Lakenheath for marine operations over the English Channel and North Sea.

In July 1943 the squadron commenced mine laying duties using the Stirling and from February 1944 performed supply drops for the Special Operations Executive. In May 1944 the squadron was moved to No. 100 (Radio Countermeasures) Group with tasking to perform radar jamming operations during the D-Day landings. The squadron aircraft also joined the heavy bomber raids over Germany but was equipped with advanced radar jamming equipment to disrupt the German air defences. In 1945 the Stirlings were exchanged for the Handley Page Halifax until the squadron was disbanded on 29 July 1945 at RAF North Creake.

Aircraft operated

Dates Aircraft Variant

1917–1919 Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 BE.2e

1942–1943 Vickers Wellington III and X

1943–1945 Short Stirling III

1945 Handley Page Halifax III

1951–1957 Avro Lincoln B2

1952–1953 de Havilland Mosquito NF36

1954–1958 English Electric Canberra B2

1957–1958 Vickers Valiant B1

No. 149 Squadron RAF

Formed on 3 March 1918 at RAF Ford, near Yapton, West Sussex, as No. 149 (NB) Squadron RFC,[9] the squadron soon moved to France for night bombing missions above occupied France and Belgium, flying Royal Aircraft Factory F.E.2s. After the war the squadron for three months took part in the occupation force in Germany, being stationed at Bickendorf, moving to Ireland in March 1919 where the squadron was disbanded on 1 August 1919.

The squadron was reformed from 'B' Flight of No. 99 Squadron RAF on 12 April 1937 under No. 3 Group RAF at RAF Mildenhall, Suffolk where it remained until April 1942. Initially equipped with Heyford biplane bombers, the squadron converted to Vickers Wellingtons in January 1939. On 4 September 1939 L4259 was flown on "Ops Brunsbüttel 4/500 GP", the day after the declaration of war against Germany by Great Britain. (Source: Pilot's Logbook).

After being re-equipped with the Short Stirling in November 1941, the squadron took part in the first 1,000 bomber raid. The squadron also formed No. 149 Squadron Conversion flight on 21 January 1942 to train new Stirling crews and on 7 October this was formed into 1657 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU) together with 7, 101 and 218 Squadron Conversion Flights. In August 1944, the Stirlings gave way to Avro Lancasters, which served the squadron until 1949. At the end of the war no. 149 squadron participated in Operation Manna, to drop food to the starved Dutch population still under German occupation, and Operation Exodus, to return former prisoners of war back to the UK.

The Short Stirling was a British four-engined heavy bomber of the Second World War. It has the distinction of being the first four-engined bomber to be introduced into service with the Royal Air Force (RAF).

The Stirling was designed during the late 1930s by Short Brothers to conform with the requirements laid out in Air Ministry Specification B.12/36. Prior to this, the RAF had been primarily interested in developing increasingly capable twin-engined bombers but had been persuaded to investigate a prospective four-engined bomber as a result of promising foreign developments in the field. Out of the submissions made to the specification, Supermarine proposed the Type 317 which was viewed as the favourite, while Short's submission, named the S.29, was selected as an alternative. When the preferred Type 317 had to be abandoned, the S.29, which later received the name Stirling, proceeded to production.

Instrument panel and controls of Stirling Mk I - photograph CH 17086 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums.

During early 1941, the Stirling entered squadron service. During its use as a bomber, pilots praised the type for its ability to out-turn enemy night fighters and its favourable handling characteristics, while the altitude ceiling was often a subject of criticism. The Stirling had a relatively brief operational career as a bomber before being relegated to second line duties from late 1943. This was due to the increasing availability of the more capable Handley Page Halifax and Avro Lancaster, which took over the strategic bombing of Germany. Decisions by the Air Ministry on certain performance requirements, such as to restrict the wingspan of the aircraft to 100 feet, had played a role in limiting the Stirling's performance; these restrictive demands had not been placed upon the Halifax and Lancaster bombers.

.jpg?timestamp=1588887643567)

Three Short Stirling bombers taking off over Great Britain, 1942-43- Office of War Information. photo Courtesy of the Library of Congress (USA).

During its later service, the Stirling was used for mining German ports; new and converted aircraft also flew as glider tugs and supply aircraft during the Allied invasion of Europe during 1944–1945. In the aftermath of the Second World War, the type was rapidly withdrawn from RAF service, having been replaced in the transport role by the Avro York, a derivative of the Lancaster that had previously displaced it from the bomber role. A handful of ex-military Stirlings were rebuilt for the civil market.

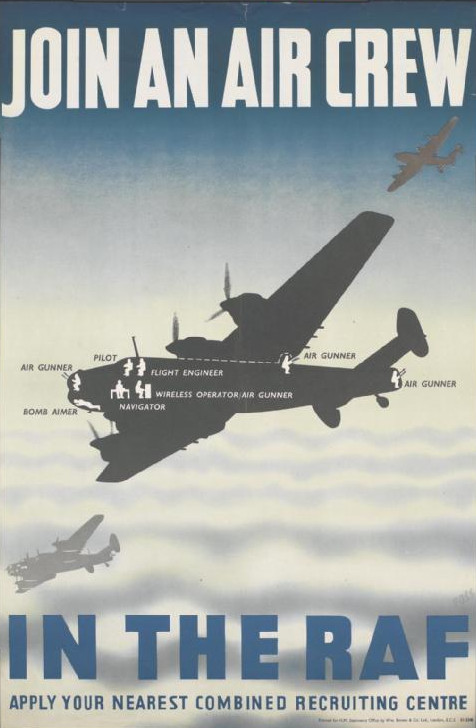

RAF recruitment poster featuring the Handley Page Halifax. Foss, Jonathan (artist), William Brown and Co Ltd, London EC3 (printer), Her Majesty's Stationery Office (publisher/sponsor), Royal Air Force (publisher/sponsor) - from the collections of the Imperial War Museums.

______________________________________

Ten Pound Poms was a colloquial term used in Australia and New Zealand to describe British citizens who migrated to Australia and New Zealand after the Second World War. The Government of Australia initiated the Assisted Passage Migration Scheme in 1945, and the Government of New Zealand initiated a similar scheme in July 1947. The migrants were called Ten Pound Poms due to the payment of £10 in processing fees to migrate to Australia. The Commonwealth arranged for assisted passage to Australia on chartered ships and aircraft. The word Pom was derived from "pomegranate" an Australian rhyming slang for "immigrant".

Assisted migrants were generally obliged to remain in Australia for two years after arrival, or alternatively refund the cost of their assisted passage. If they chose to travel back to Britain, the cost of the journey was at least £120 (in 1945 pounds, equivalent to £5,217 in 2019), a large sum in those days and one that most could not afford.

Post-war rationing in the U.K. made the sunshine and potential for access to more food, and good food, of Australia very attractive. There were many who emigrated that later made significant contributions to our nation. Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, migrated in 1960 under the scheme, although his father had already lived in Australia after arriving at the beginning of the Second World War on a Blue Funnel Liner, and his mother was an Australian expatriate living in Britain at the time of his birth. The Bee Gees (Gibb brothers) spent their first few years in Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Manchester, England, then moved in the late 1950s to Redcliffe in Queensland, where they began their musical careers. The five original members of the Easybeats migrated independently and formed their band after arriving in Sydney. Lead singer Stevie Wright migrated from Leeds, England. Harry Vanda migrated from the Hague, Netherlands, and George Young migrated from Glasgow, Scotland, to become the twin guitars and later the songwriting team that took the Easybeats to the world with "Friday on My Mind". George's younger brothers Malcolm Young and Angus Young formed the twin guitars of AC/DC, with another immigrated Scotsman Bon Scott. Grace McNeil (née Greenwood) and Christopher John Jackman, a Cambridge-trained accountant, migrated to Australia in 1967 where their son, Hugh Jackman, was born in Sydney.

Upon arrival, migrants were placed in basic migration hostels and the expected job opportunities were not always readily available. It was a follow-on to the unofficial Big Brother Movement and attracted over one million migrants from the British Isles between 1945 and 1972, representing the last substantial scheme for preferential migration from the British Isles to Australia.

Sydney Andrew Coventry (13 June 1899 – 10 November 1976) was an Australian rules footballer. Originally from Diamond Creek, Victoria, Coventry journeyed across the Bass Strait after the First World War to work in the mines at Queenstown, Tasmania, taking with him a reputation as a fine footballer.

Coventry first played for a Queenstown based team in 1919, but was appointed Captain of the Miners team from Gormanston for the 1920 season. The team played in the Queenstown based ‘Lyell Miners Football Association’ which included 9 teams. Gormanston was a small miners town at the top of Mount Lyell. The footballers in the region are noted as some of the hardiest in Australia given the weather and playing conditions, which include the famous Gravel Oval at Queenstown.

While still in Queenstown Coventry was approached by St Kilda who wanted him to play for them in 1921. Syd duly agreed, but when he returned to Melbourne he was persuaded by his younger brother Gordon Coventry, who had just finished his first season with Collingwood, to reconsider. Apart from the issue of family loyalty, there was the small matter of the excessive distance between Diamond Creek and St Kilda to think of.

%20and%20his%20brother%20Gordon%20were%20footy%20stars%20of%20the%201920s%20and%2030s..jpeg?timestamp=1588888654642)

Syd Coventry (left) and his brother Gordon were footy stars of the 1920s and 30s.

The upshot of it all was that Syd Coventry elected to throw in his lot with Collingwood, whereupon St Kilda, not surprisingly, screamed "foul!" The VFL Permits Committee was called in to adjudicate, and Coventry was faced with the choice of playing with St Kilda, or sitting out of football for twelve months so that he could join the Woods. He opted for the latter course of action, and in 1922 he started out on an illustrious thirteen season, 227 game league career with Collingwood.

Despite standing only 180 cm in height, Syd Coventry played mainly as a ruckman, where his aggression, vigour and dynamism more than compensated for any deficiency in stature. A born leader, he captained the Magpies from 1927 until he moved to Footscray as coach at the end of the 1934 season. He thus enjoyed the unique privilege of captaining four successive VFL premiership teams.

Often at his best when the going was rough, one of Syd Coventry's finest performances came on a waterlogged MCG in the 1927 grand final, when Collingwood and Richmond between them could manage only 3 goals for the match. The 1927 season also saw him win both the Brownlow Medal and Collingwood's best and fairest award. He repeated the second achievement five years later.

Coventry till this day remains the only Premiership Captain to win a Brownlow in the same year. For good measure, he was named the best player in that year's Grand Final. As a Captain, Syd led Collingwood Football Club in 144 games. In that period Collingwood won 111 games, drew twice and lost 31 times. A winning ratio 77 percent, an VFL/AFL record. A virtual ever-present in VFL representative teams for most of his career, Coventry made a total of 27 interstate appearances. His eventual departure from Victoria Park to coach Footscray came with the blessing of the Collingwood committee, but only on the proviso that he did not continue as a player.

Two of his for sons, Hugh in 1941, and Sydney, in 1954, had brief careers with Collingwood.

A NEW COVENTRY

The name of Coventry seems destined to remain with Collingwood for a long time. On Saturday, Hugh Coventry, son of Syd., the former captain, and nephew of Gordon, greatest forward the game has known, scored four goals. At first he was stationed on the half-forward flank, but did not show up. Transferred to a forward pocket, he immediately got among the goals. His style of kicking is strongly reminiscent of his uncle. A NEW COVENTRY (1941, July 26). Weekly Times (Melbourne, Vic. : 1869 - 1954), p. 39. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article224830700

"AUSSIE RULES" IN ENGLAND

Bruce Andrew Kicks 13 Goals

The Herald Special Service

LONDON, Tuesday. — In the second inter-unit Australian rules football match played In England this season, RAAF H.Q. defeated No. 10 RAAF Flying Boat Squadron by 20 gonis 7 behinds (127 points), to 6 goals 2 behinds (38 points). Captains were Flt.-Lieut. Bruce Andrew, former Colllngwood footballer, who kicked 13 goals for Headquarters; and Flt.-Sgt. W Mackie, from Essendon, who skippered No. 10 Squadron. Outstanding players in the match were Flt.-Sgt. Hugh Coventry (Collingwood). LAC N. Tempest (Yarraville), Sgt. E. W. Ashcroft (Coburg) Sgt H Huxtable (South Australia) and Sgt. A. Eaton (Tasmnnin). Organisers of RAAF football In Britain are now planning a "Victoria v. Rest of Australia" match, to re-Introduce Australian rules to Londoners, who have not seen it since the 1916 game during the last war. Three Rugby footballers from Sydney have been chosen for combined RNZAF-RAAF-RAF side to meet Scotland In a Rugby match at Edinburgh on New Year's Day. They are Flt.-Lieut. J. B. Nichols and Flying-Officers Peter Glanville and Douglas Hughes. "AUSSIE RULES" IN ENGLAND (1943, December 15). The Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 - 1954), p. 8. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article245794030

FOOTBALLER GAINS HIGH AWARD

DFC to Flight-Lieut Hugh Coventry

By PERCY TAYLOR

Flight-Lieut Hugh Coventry, who was just settling down lo good football at Collingwood when he enlisted, and who has been overseas for some time, has been awarded the DFC.

His father, Syd, one of the best players of his day-he was a Brownlow Medal winner and club and Victorian captain-has just been informed of the honour. FOOTBALLER GAINS HIGH AWARD (1945, March 31). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), p. 12. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1105108

Gordon Richard Coventry (25 September 1901 – 7 November 1968) was an Australian rules footballer who played for Collingwood Football Club in the Victorian Football League (VFL). Accorded "Legend" status in the Australian Football Hall of Fame, Coventry was the first player to kick 100 goals in a season and over 1000 goals overall, with his career total of 1299 goals serving as a league record for over 60 seasons.

Originally from Diamond Creek, Victoria, Coventry played his early football for the Diamond Creek Football Club in the Heidelberg District Football League (HDFL). He debuted for Collingwood in 1920, and was joined by his brother, Syd Coventry, at the club two years later. Playing almost exclusively at full-forward, Coventry first led Collingwood's goalkicking in 1922, and would go on to lead the club's goalkicking for 16 consecutive seasons, until his retirement in 1937. He also led the VFL's goalkicking on six occasions: each year from 1926 to 1930, and then again in his final season. In 1929, Coventry kicked 124 goals for the season, becoming the first player in the league to kick over 100 goals in a season, a feat which he would replicate in 1930, 1933, and 1934. Considered the leading forward in the competition in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Coventry played a key part in Collingwood's four consecutive premierships from 1927 to 1930, each captained by his brother. He also went on to win the Copeland Trophy as Collingwood's best and fairest player in 1933. At his retirement at the end of the 1937 season, Coventry held the records for the most career games played and the most career goals kicked, finishing with 1299 goals from 306 games, and thus also becoming the first player to play 300 games. An inaugural inductee into the Australian Football Hall of Fame, and a member of Collingwood's Team of the Century, his career goalkicking record was not broken until 1999, when it was surpassed by Tony Lockett. He is often considered by fans and journalists to be amongst the greatest forward-line players of all time.

Tommy Knox on Parade in Mona Vale, Anzac Day 2020 - photo by Michael Mannington