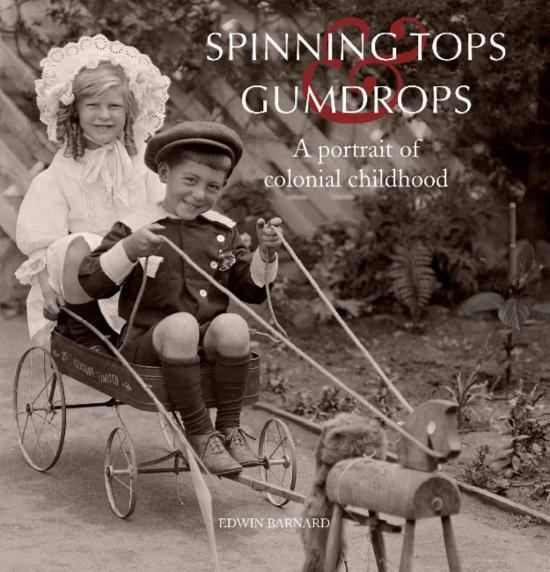

Spinning Tops and Gumdrops: A Portrait Of Colonial Childhood

Whenever Pittwater Online News have found and run photographs or articles that show the presence of local children in a historical context the images and text have promptly been shared around by residents from one end of the peninsula to the other and even further afield.

For all of you hungry for more insight into the childhood's of earlier generations of Australians you will be thrilled to know one of our local authors has put some time and effort into finding the spectrum of a colonial childhood and giving these youngsters a voice.

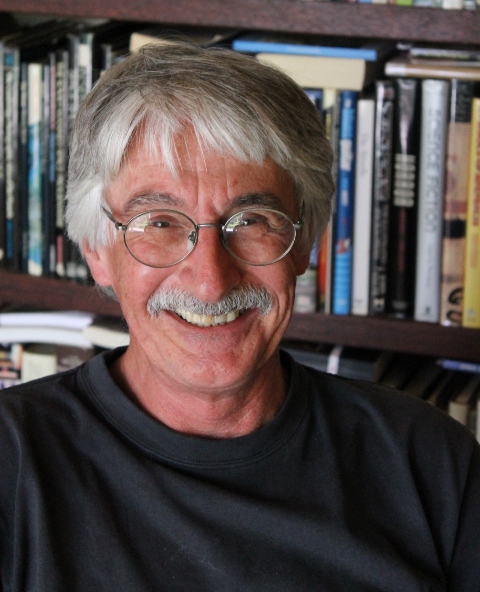

In 'Spinning Tops and Gumdrops: A Portrait Of Colonial Childhood Edwin Barnard tells the story of six generations of children, the offspring and descendants of convicts and settlers, who grew up in Australia between 1788 and around 1900. The Avalon author has accessed memoirs and reminiscences to compile an insight into the everyday lives of children for whom the smell of a horse, studying by candle or working in a tweed mill were what they knew.

In 'Spinning Tops and Gumdrops: A Portrait Of Colonial Childhood Edwin Barnard tells the story of six generations of children, the offspring and descendants of convicts and settlers, who grew up in Australia between 1788 and around 1900. The Avalon author has accessed memoirs and reminiscences to compile an insight into the everyday lives of children for whom the smell of a horse, studying by candle or working in a tweed mill were what they knew.

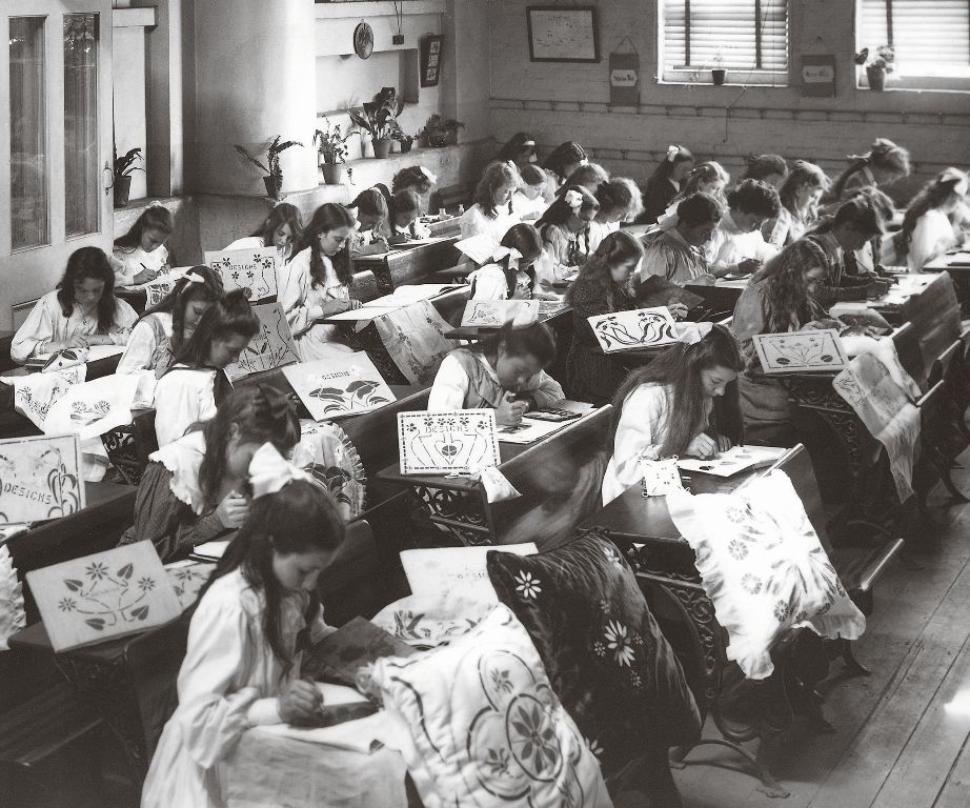

Through six chapters, illuminated with photographs, drawings and paintings, some of them from Mr. Barnard's own collection, this book delves into the world of the European emigrant and the life of the child who lived in a rural area or those who played in the streets.

Pittwater Online recently spoke to Edwin about his latest work.

Why 'Spinning Tops and Gumdrops' as the title - where is this from?

Since the cover image and subtitle make the subject matter clear enough, I thought the main title needed to be quirky enough to encourage browsers to at least pick the book up and flick through it. If you don't know what spinning tops and gumdrops are you might be tempted to look inside to find out (both are in the index). If, on the other hand, the names conjure up memories of your own childhood (or of stories told to you by parents or grandparents) you might fancy a trip down memory lane.

The six generations - how long did it take to find all these wonderful anecdotes?

All anecdotes used in the book came from memoirs and reminiscences. It took over a year to track them down, read them and gather together those passages that throw light on some aspect of daily life. I have tried in this book, as with my other books, to allow those who lived in colonial Australia—in this case, particularly the children of working people—to speak for themselves. This is less a history book than a colourful patchwork of personal stories, woven together with a collection of great images and enough background material to make sense of any unfamiliar details. The overall aim is to give readers a real feeling for the flavour of a nineteenth-century childhood, as well as a good read.

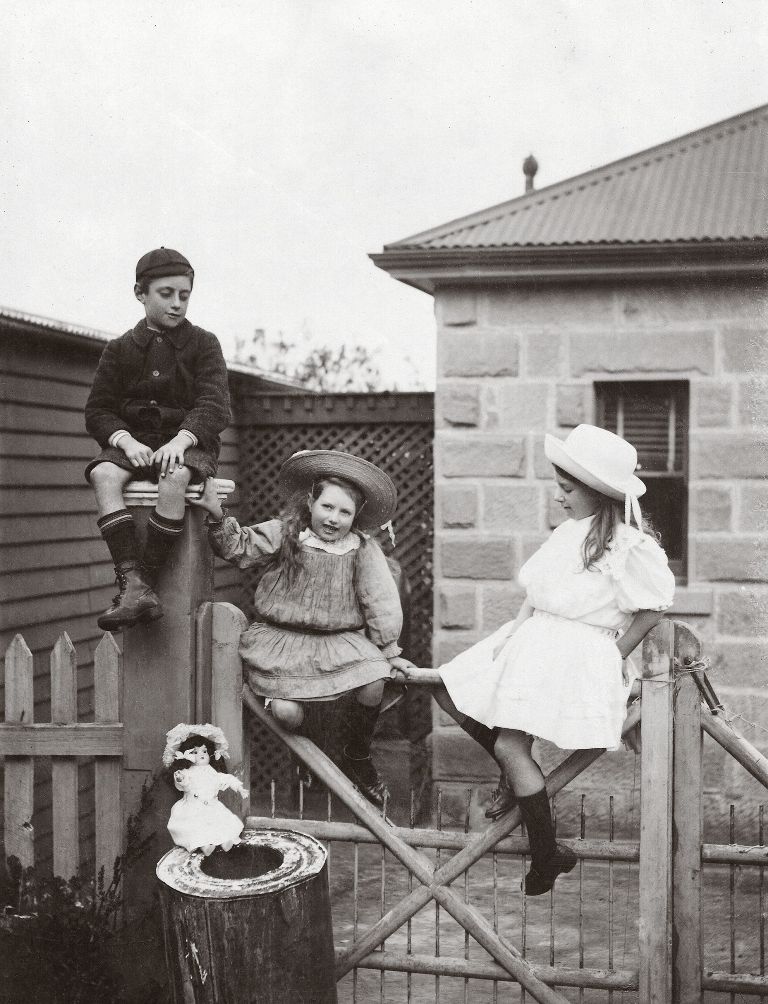

From Page 63 - Children on fence, Hobart, 1890's; author's collection.

The Chapter A Country Childhood speaks of recourse to books hard earned - or newspapers read for the pictures; how important were these for a child?

It's hard to imagine today, in a world awash with images, what it must have been like to live in an age when pictures were something of a rarity. In the 1850s the only illustrations available to most children were those to be found in books, and few working-class households could muster more than a couple of tattered volumes for the family bookshelf. Among those volumes was almost certainly a family Bible, and quite possibly a copy of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. Engravings of the parting of the Red Sea, the Deluge, the Plagues of Egypt, Giant Grim, the Slough of Despond and Vanity Fair could leave an indelible mark on an impressionable young mind. Indiana Jones and Darth Vader might have trouble competing. It was probably not until the arrival of the illustrated papers in the 1870s that poor households had any pictures to stick up on the wall.

In 'Our Playground was the Street' - was there really the 'street urchin here alike Dickens famous portrayals?

Every colonial capital had its complement of 'street Arabs', members of a tribe that would have been familiar to Charles Dickens. A few were homeless urchins living off their wits, but most came from poor but respectable households. When families with ten or more children were compelled to live in a couple of rooms there was nowhere to play but out on the street. Gangs of rowdy children certainly cluttered up suburban pavements every day, annoying passersby with their games of hopscotch and marbles, but they generally had homes to go to. Those who were sleeping rough—among them the Sobraon boys, whose portraits are a feature of the book—were liable to be picked up by police and packed off to an industrial school to learn a trade.

What one or two examples to you points out what is different between a colonial childhood and the childhood of a 21st Century child?

Apart from the clothes, I'm not sure anyone transported back to a Sydney street in the 1880s would notice a great deal of difference in the way children behaved among themselves. Children are and were just children. What has changed, however, is parental expectations. Children were part of the family, and as such were expected to contribute. There were the usual domestic chores, of course: babies and toddlers to be looked after, cleaning and tidying to be done, eggs to be fetched, cows to be milked and horses to be rounded up and harnessed. But more than that, children were expected to find a paying job as soon as their labour could be put to good use. For some boys and girls that meant taking their place on the factory floor or behind the plough when they were only nine or ten years old. The paltry wage they earned, often paid directly to their parents, helped to put food on the dinner table every day.

From Page 61; Boys playing soldiers, J. F. Barnard, c1900; State Library of Victoria, accession no.H2002.125/30.

In the chapter titled 'We All Had To Do Something', meaning everyone must do some form of work - did your research point to this ending childhood or did a sense of play persist?

I don't think children ceased to be children after they started work, although the opportunities for play was greatly reduced. The 50 or so children employed at Vicars Tweed Mill in Sydney in 1876—half the workforce—started at six in the morning and finished at six at night. But they did have 45 minutes off for breakfast and an hour for dinner at midday, and many played together then, or lounged around outside the factory gates smoking and yarning. It was most surprising to discover that some even attended night school after work, although there must have been many like poor little 11-year-old Kate McInlay who confessed that she had trouble staying awake.

Spinning Tops & Gumdrops: A Portrait of Colonial Childhood

By Edwin Barnard

Published by the National Library of Australia, March 2018. Available here: $44.99

'Spinning Tops and Gumdrops' takes us back to childhood in colonial Australia.

'Spinning Tops and Gumdrops' takes us back to childhood in colonial Australia.

The delight of children at play is universal, but the pleasure these children experience as depicted through the book's photographs is through their 'imagination, skill and daring' rather than through possessions.

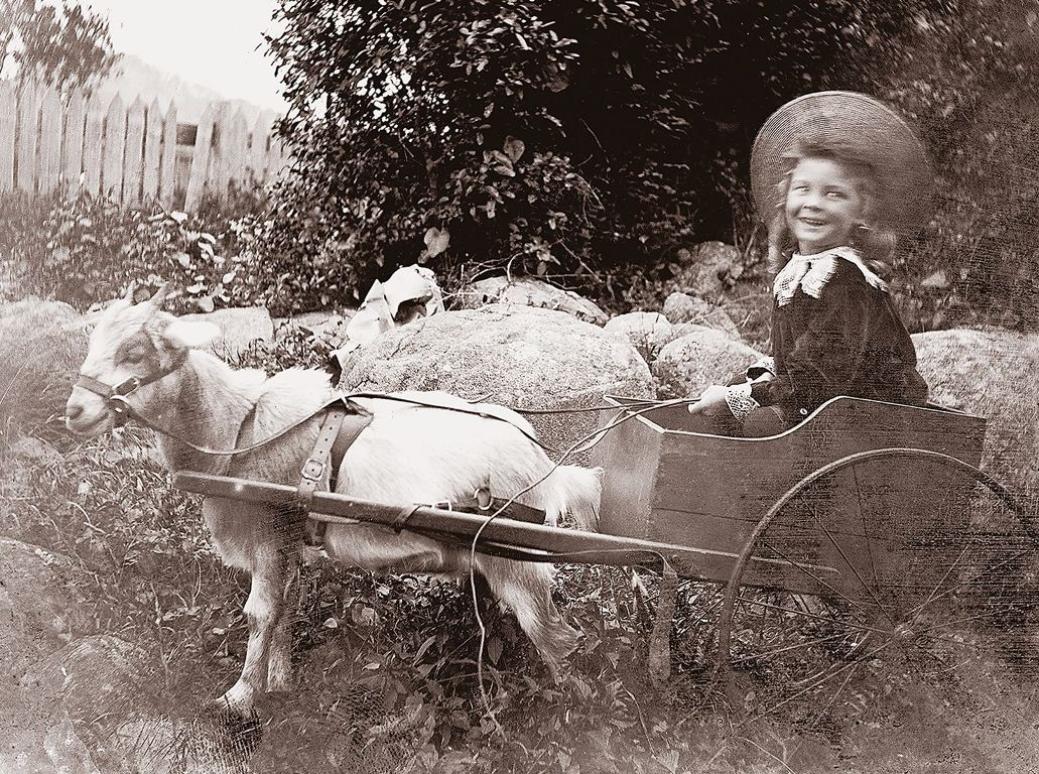

Children play quoits and jacks, hide and seek, cricket with a kerosene tin for a wicket, dress ups and charades. They climb trees, run races, and build rafts to sail on the local waterhole. The photographs show children happily absorbed in the play of their own making.

Being a child in colonial Australia was also tough. It was a time when school yard disagreements were sorted out with fists and 'the loss of a little claret'. A time when children could view public hangings and premature death was frequent, especially taking the very young and vulnerable though dysentery, whooping cough or diphtheria.

The lasting impression left by the contemporary accounts, photographs, etchings and paintings of colonial children in 'Spinning Tops and Gumdrops' is their possession of qualities of resilience, self-sufficiency and acceptance of their lot. Perhaps it was through lack of choice, or of knowing no other. Nevertheless, these were qualities that put them in good stead for the challenges many faced in their adulthood.

Interestingly, these are qualities on which contemporary society still places a high value, but which today seem a little more elusive.

a few local children:

A Barranjoey Lighthouse child - from EB Studios (Sydney, N.S.W.). 1917, Panorama of Palm Beach, New South Wales, 14 , PIC P865/6/1 LOC Nitrate store, (zoomable at http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-162567120 ) and sections from – courtesy National Library of Australia -

Visit The Barrenjoey School 1872 to 1894

Small schoolboy loitering at Mona Vale shop Above and Below: Panorama of Mona Vale, New South Wales, ca. 1930 [picture] / EB Studios National Library of Australia PIC P865/125 circa 1917-1921 and section from made larger to show detail.