Ross River Fever in Pittwater: what you can do to Beat those mosquitoes

Dr Cameron Webb from NSW Health Pathology, Principal Hospital Scientist in Medical Entomology, NSW Health Pathology, Clinical Lecturer with Marie Bashir Institute for Infectious Diseases and Biosecurity (MBI), University of Sydney and Senior Investigator with Centre for Infectious Diseases & Microbiology Public Health stated earlier this month that has been a rise in mosquitoes and cases.

"We've seen an explosion in mosquito populations," he said.

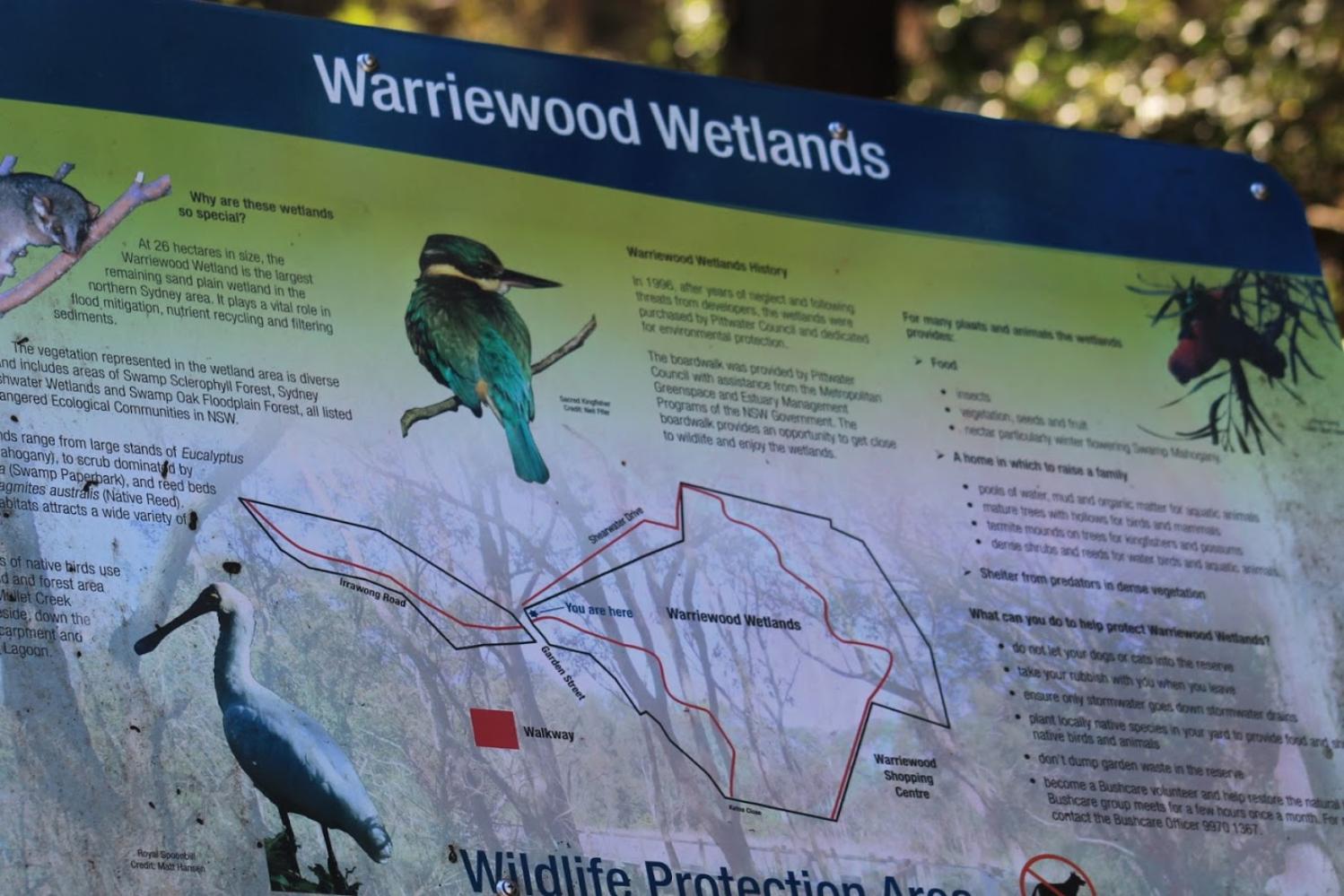

Mosquitoes carrying the disease have been found around Narrabeen and the Warriewood wetlands, around Georges River, Parramatta River and the Hawkesbury. There has also been a spike of cases recorded on the Mid-North Coast. In April 2020 434 cases of the virus were recorded in NSW – more than five times the amount documented in April 2019, making it the state's highest number of infections in almost 30 years.

Dr Cameron Webb, on his Beat the Bites: Mosquito Research and Management website states Ross River virus is the most commonly reported mosquito-borne disease in Australia. The virus is spread by the bite of a mosquito and about 40 different mosquito species have been implicated in its transmission.

"In Sydney we know we have a high concentration of mosquitoes which is a symptom of the poor health of the wetlands. Rehabilitation of those wetlands can reduce the quantity of mosquitoes produced.

"But as we also open up coastal areas to urban development, people are living closer to wetlands than they were before. Also, people moving to areas like this from the city for example, are not fully understanding the health risks of mosquitoes or taking the appropriate measures to avoid being bitten."

''Coastal wetlands around Sydney are impacted in many ways. Mangrove forests and saltmarshes are degraded through direct and indirect human activity. There is recent research indicating that sea level rise is impacting mangroves along the Parramatta River in Sydney. This requires active management to ensure substantial degradation and die back occurs, as has been seen elsewhere in Australia.

Some of our research even suggests that degraded mangroves are more productive when it comes to mosquitoes. Effective rehabilitation of these habitats may actually reduce the mosquitoes flying out of these environments and impacting the community nearby. Similarly, urban planning should consider the risk posed by mosquitoes in wetlands adjacent to new and expanding residential developments. This includes major wetland rehabilitation projects.''

It is important to remember that mosquitoes are a natural part of wetland ecosystems. While often their pest impacts may indicate the poor health of the wetlands, at other times abundant mosquito populations are a natural occurrence that fluctuate in their intensity from year to year.

It is also important to remember that there are many mosquito species associated with wetlands, especially freshwater habitats, that pose no substantial threat to humans. There are hundreds of mosquitoes in Australia, and less than a dozen really pose a substantial pest or public health threat. Many mosquitoes may play an important ecological role in wetland ecosystems. This may include representing a locally important food source for insectivorous wildlife or pollinating plants.

The disease caused by Ross River virus is not fatal but it can be severely debilitating. Thousands of Australian’s are now infected each year.

Researchers have some idea of the quantity of infections as Ross River virus disease is classified as a notifiable disease. While the official statistics indicate there are around 5,000 cases of illness across the country (there are between 500 and 1,500 cases per year in NSW), there are likely to be many more people that experience a much milder illness and so never get blood tests to confirm infection. These people won’t appear in official statistics.

What makes Ross River virus a fascinating pathogen to study is also what makes it extremely difficult to predict outbreaks. Transmission cycles require more than just mosquitoes. Mosquitoes don’t emerge from local wetlands infected with the virus, they need to bite an animal first and become infected themselves before then being able to pass on the pathogen to people.

It is generally thought that kangaroos and wallabies are the most important animals driving outbreak risk. However, scientists such as Dr. Webb are starting to better understand how the diversity of local wildlife may enhance, or reduce, likely transmission risk.

The recent warnings have been triggered by the results of mosquito trapping and testing around Sydney. NSW Health coordinates an arbovirus and mosquito monitoring program across the state and this includes surveillance locations within metropolitan Sydney.

Mosquitoes are collected using traps baited with carbon dioxide. They trick the mosquitoes into thinking the trap is an animal. By catching mosquitoes, they can better understand how the pest and public health risks vary across the city and the conditions that make mosquitoes increase (or decrease) in numbers.

Ross River Fever mostly occurs around the metropolitan region’s northern and southern river systems and generally associated with estuarine or brackish-water wetlands. In these areas, there are often abundant mosquitoes and wildlife. Along the Parramatta River, there are often abundant mosquito populations but given the heavily urbanised landscape, there aren’t many kangaroos and wallabies.

The nuisance impacts of mosquitoes, such as Aedes vigilax, Australia's saltmarsh mosquito, dispersing from the estuarine wetlands can create challenges for local authorities. These challenges include targeted wetland conservation and rehabilitation strategies along with ecologically sustainable mosquito control programs.

The saltmarsh mosquito, Aedes vigilax, transmits Ross River virus in many coastal regions of Australia. Photo: Mr Stephen Doggett (Medical Entomology, Pathology West - ICPMR Westmead)

The detection of Ross River virus is not that unusual. Detection of Ross River virus (as well as other mosquito-borne viruses such as Stratford virus) along the Georges River in southern Sydney is an almost annual occurrence. The local health authorities routinely issue warnings and in recent years have successfully used social media to spread their messages.

While there have been confirmed local clusters of locally acquired Ross River virus in the suburbs along the Georges River, there have been no confirmed cases of Ross River virus disease in the suburbs along the Parramatta River. Along the Georges River, there is clearly a higher risk of infection given the more significant wildlife populations, especially the wallabies common throughout Georges River National Park. By comparison, along the Parramatta River there are fewer bushland areas and virtually no wallabies. Even in the wetland areas around Sydney Olympic Park, there is abundant bird life, meaning mosquitoes are probably more likely to be biting the animals than people. A study looking at the blood feeding preferences of mosquitoes in the local area found that animals were more likely to be bitten, mosquitoes actually only fed on humans about 10% of the time.

There are a few reasons why more disease isn’t reported. Health authorities are active in promoting personal protection measures, sharing recommendations on insect repellent use and providing regular reminders of the health risks associated with local mosquitoes. These actions raise awareness and encourage behaviour change that reduces mosquito bites and subsequent disease.

"There is a role to play for both local councils and the health department about making sure good, clear messages are shared in the community to avoid mosquito bites. And this is done in most parts very well done by state health authorities," Dr Webb said.

"Like any public health message, we need to ensure the community gets the best advice to make those changes and to avoid being bitten. That can be from choosing the right sorts of repellents to reducing the opportunities for mosquitoes to breed in your own back yard."

Local councils across New South Wales trap mosquitoes and send to NSW Health Pathology for weekly testing from the start of Spring through until the middle of Autumn.

On April 30th, 2020 the Northern Beaches Council issued a statement to the effect that Ross River virus and Barmah Forest virus were detected in mosquitoes collected at Deep Creek in late March. Ross River virus was also detected in mosquitoes collected in the Warriewood Wetlands in early April.

A study published in May 2019 by Dr Cameron Webb, Dispersal of the Mosquito Aedes vigilax (Diptera: Culicidae) From Urban Estuarine Wetlands in Sydney, Australia, demonstrates that Australia’s saltmarsh mosquito (Aedes vigilax) flies many kilometres from urban estuarine wetlands, so it's better to be safer than sorry, wherever you live.

It is important that if you’re spending a lot of time outdoors in these areas, especially close to wetlands and bush land areas at dawn and dusk when mosquitoes are most active, that you take action to reduce the risk of being bitten. Cover up with long sleeved shirts and long pants and apply an insect repellent. Choose a repellent that contains either DEET (diethlytoluamide), picaridin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus. Apply it to all exposed skin to ensure there is a thin even coat – a dab “here and there” doesn’t provide adequate protection.

You can also reduce the incidences of mosquitoes breeding by removing any shallow dishes of water or, if you have these out to feed wildlife and birds, regularly change the water so the stagnant water climate for them to breed is removed (more tips here). Outbreaks can occur when local conditions of rainfall, tides and temperature promote mosquito breeding, so if we have rain followed by a warm day, check any receptacles in your garden and make sure they are emptied of water.

It is also a good idea to ensure you're not being bitten while asleep - repair any flyscreens that are damaged, or install them where absent. There are also a range of plants you can incorporate into your garden that repel mosquitoes and attract mosquito eating insects, such as dragonflies, or birds, possums, frogs and bats that will also reduce their numbers by eating them.

Similarly, if you're out and about in our wetland areas not chasing off or disturbing the wildlife that lives there, such as turtles or ducks, with ducklings just a few days old known to eat mosquitoes, will help.

Chestnut Teal, Anas castanea, Warriewood wetlands - photo by A J Guesdon

Also, keep in mind that just because cooler weather has arrived, the health risks associated with mosquitoes remain. That means keeping in mind that mosquitoes may be out and about just as football, rugby and netball seasons finally start so take along some mosquito repellent to training nights. The risk will abate as weather cools further still, but remaining vigilant will lessen your risk of being bitten by an infected mosquito.

Symptoms of Ross River Fever include a rash, fever, aching joints and fatigue. Symptoms usually develop about 7-10 days after being bitten by an infected mosquito. The majority of people recover completely in a few weeks, others may experience symptoms such as joint pain and tiredness for many months. For more visit this NSW Health Ross River Fever fact sheet and Explainer: what is Ross River virus? - by Dr Cameron Webb

For more Dr Cameron Webb articles and research projects visit his Beat the Bites: Mosquito Research and Management website or visit The Conversation for more of his articles.