September 25 - October 1, 2016: Issue 282

Kurt and Robin Ottowa

Robin Ottowa, Captain of the RMYC Multihulls Division, and his father Kurt will be ‘friendly rivals’, even sailing together in the Ocean Race leg of this year’s Lock Crowther Regatta.

Running over the October long weekend, September 30 to October 2nd, this is one of the fastest most exciting and friendliest regattas the Pittwater Estuary hosts each year through the Multihull Division.

Kurt’s fleet flyer is ORCA, 51, while Robin will be sailing his LUKIM YU, 101, a trimaran.

Robin to the left and Kurt is to the right

Both gentlemen are fearless in life and this has transposed to being fearless practical sailors. Both have a great work ethic and make opportunities for themselves. As a family they came to Australia seeking a new life and found opportunity approached with the right attitude does bring rewards, things that may not be measured so easily by those who have not travelled such roads.

Where were you born?

Kurt: In Sudetenland – which is a German area between Czechoslovakia and Poland. We were the reason why World War II started.

Did you grow up there?

Kurt: Yes, until the end of the war, 1945. I was 10 years old when this then became West Germany.

Do you have many memories of that war?

Kurt: Oh yes: bombing, dead people, you never forget those things. It’s a different life now, that’s all in the past.

West Germany – what was your family doing there?

Kurt: We became refugees. We settled in a place near Munich and that’s where I met my wife Krimhilde, I was only 17. We’ve been together for a long long time.

Did you attend university there?

Kurt: Oh no, there was no such thing because you had to get your head down and work hard so there was no time for that. I was a painter, Master Painter, that was our trade. My father came back from Siberia in 1950 and soon after that he started his business in a little place called Freising and from then on that’s all I ever knew; painting.

Your father was a P.O.W.?

Kurt: Yes, he was a prisoner of war and spent five years after the war ended in Siberia. He as captured in what is known today as Gdańsk but was then called Danzig. We didn’t hear from him for around three years and then he was found through the International Red Cross and we then knew he was stuck away in a camp in Siberia.

When did you come to Australia?

Kurt: We came in 1960. Robin was our youngest then and in fact was the youngest passenger on the boat at 8 months old.

Robin almost died on the journey out he became so ill, nobody knew what was wrong, he was throwing up blood, it was terrible. In those days we didn’t get any support we were shepherded into a boat which was built initially for 800 passengers and there were 2500 of us. It was bad.

On top of that we had a very long voyage because we had an Egyptian pilot on board who was drunk and he ran the boat aground in the Suez Canal. We had to wait in Eden for a new captain and then began the rest of the journey to Australia.

Finally, on Good Friday 1960, we arrived in Freemantle.

I found out later on this was the same boat Eddie Maguire’s parents came out on.

National Archives: OTTOWA Kurt born 24 March 1935; Krimhilde (nee Beer) born 12 November 1936; Oliver born 24 February 1956; Robin born 18 August 1959 - German - travelled per CASTEL FELICE on 13 March 1960

What were your first impressions of Australia?

Kurt: Freemantle? I thought ‘what have I done?!’ – there were no signs in English, everything was in Greek and Italian in those days. It was rundown, it was dirty, it was very basic then.

All that changed when we came further on to Melbourne. Melbourne was civilised.

How did you come to Sydney?

Kurt: I started with a company in Melbourne as a Painter. When I saw the so-called workforce I said to my friend who came out from Germany too ‘if we don’t make it here, we’ll never make it anywhere.’

I worked hard and within a year I was made a Foreman, then they wanted to make me a Supervisor but that didn’t work as the rest of the employees were against it. the company then took over a business in Adelaide and there was a hance for me to start a branch in Adelaide, which I took.

They then called me back and said ‘we have the big one coming up in Sydney. a company here in Sydney went bust and we took it over and this became the biggest painting organisation in the Southern Hemisphere. In the heyday we employed around 800 people throughout Australia.

It was just before Kennedy was killed in 1963. I remember it was a Saturday, we had lots of work in the office going on in Pyrmont, in Market and Kent Street. I turned the radio on in the car and I heard the latest news; ‘Just to repeat, Kennedy has been shot’.

We rented a place near Tom Ugly’s Bridge, near Hurstville, when we first came to Sydney. then the company got bigger and I became a manager and finished up as General Manager of the company.

We then went public, for a company, made some money out of it. Unfortunately there were then some people who entered the company who had no idea about the business and the company started to go down. I said then ‘now is the time for me to get out’ and that’s when I decided to jump.

I started my own little business then and Rob became part of this. We separated because he wanted to make a bigger business and I wanted to stay smaller. Robin stared his own business and I retired.

What was it like growing up in Hurstville?

Robin: We didn’t really grow up in Hurstville as we moved to Wheeler Heights soon after we came to Sydney, in 1966 and then to Cromer in 1969.

Kurt: yes, I wrote in the wet concrete the date.

Robin: Cromer was good because we had the bush there and the surf and us kids would ride dirt bikes there.

Kurt: he had a bike he turned the area upside down with – he went everywhere.

Robin: I still have them.

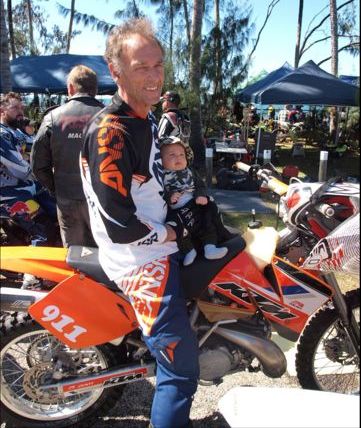

Robin, still bike racing a few weeks ago, the other photo is with his grandson

Kurt: I must say, that from the first day we arrived in Melbourne, life was great. We worked hard, often I was away for two or three months in the country painting Service Stations, but it was worth it.

In those days an ordinary Painter would earn about £20, well I never had a week under £40.

Robin: when we first got off the boat we went to this place called ‘Bonegilla’, which was a Migrant Camp on the Albury-Wodonga border.

This had been an old 1920’s Army Barracks that had been converted. I actually went back there last year as they’d turned it into a Migrant Museum, and it was pretty spartan. There were fibro rooms and a family would be in a 3 metre by 3 metre room with some bunks. They had a plaque on the wall which reads ‘they weren’t used to the fat in the mutton’ – all the Europeans got sick from the food.

Kurt: I lasted one day there. I then went over the fence and hitchhiked to Melbourne looking for a job. We were told ‘don’t you leave the camp, you’re not allowed to do that’.

I thought ‘bugger you’ (I’m getting on with it).

One thing I found out all the way through and that is, timing is everything in life. To walk onto that place where I got the job in Melbourne, to walk onto that place where I live to do a little touch-up, where it’s a yachties paradise – this has recurred for me. That’s why I say ‘timing is everything’.

How many children do you have Kurt?

There’s Oliver, he’s in China teaching English. Then Robin, who has been very successful in his building his company. We also have a daughter, Susan.

Where did you go to school Robin?

Robin: I attended Wheeler Heights Public School then went on to Aloysius in Milsons Point in 1973. I used to catch the old green double decker bus with the back opening from Collaroy Plateau and it would take around an hour and a half to get there. This was a good school, run by Jesuits. It was a big of a shock coming from a public school in the outer suburbs to one where they’re trying to teach you Latin. I was a bit ‘who wants to learn Latin?!’

It was all about getting your brain going really. In some ways I think they maintained this because there was a bit of medical snobbery to keep the plebs out, so they’d pronounce everything in Latin – instead of calling them by their normal names they call them by their Latin names and this seemed a bit of elitism to squeeze the average person out.

What did you do when you left school?

Robin: I finished my Sixth Form and went to work for Westpac in Foreign Exchange. This was a good job, I was a Foreign Teller within three months, which usually took two years to gain. They were then going to put me into the International Division, where you did Exchange Contracts and looked after all the Foreign Currencies but I wanted a loan for a car and they wouldn’t give it to me, so I left.

Kurt: there was also an added incentive. My wife and I were preparing the wages, we had three or four painters at that time, and ob came around looked at it and said ‘oh, you’re paying them fortnightly now.’

I said, ‘no, weekly.’ – that was it.

Robin: I used to do Painting during the school holidays, so had experience to go into that, but the real reason I left is because they wouldn’t give me the loan for the car. I saw the other guys there who were really unhappy and stayed because in those days they used to have really cheap loans, they were 2%. All these guys kept whinging they were really unhappy and when I said ‘well leave’ they replied they’d then have to pay full price for their mortgage. The ‘job for life’ scenario had captured them for life.

As well it was very regimental in those days so the amount of years you’d stayed is what position you got, it wasn’t based on ability. It’s changed quite a lot now.

I quite enjoyed the bank apart from the regimentation where you had to respect someone just because they were senior and even if they weren’t too good at what they were doing.

So you went in with your dad?

Robin: Yes, I did this with dad for around 20 years until dad got a little bit sick and I got married and wanted to expand the business. I began Summit coatings and have my wife Conny working in the office and we have Sarah, another secretary and I have a Pricer that runs around, and I also run around and we employ around 30 guys now.

Do you enjoy working for yourself?

Robin: The good thing I like about it is when it’s doing well it’s great, you can look after your boys, and all our boys are really good at their work. It’s a bit of a family, everyone works well together and gets on.

The bottom line is though if you’re turning over 4 million dollars worth of work a year you are going to have a certain amount of problems. Once in a while, because it’s such a big organisation, you have to deal with something that’s not as you want to be and ensure that standard you want is maintained. It’s a numbers game when you’re doing that amount of work and you want to know the highest standard possible is what always happens, that’s where you get your own satisfaction from.

When you have that amount of workforce you have to pull in a certain amount of work each week and ensure you are replacing it to create that workflow, so that can be a challenge. You have to keep peddling.

When it works it’s perfect, when it doesn’t, such as four years ago when we had a bit of a recession and people weren’t spending money, it’s tough – you’re actually losing money every week. When the economy is flat for one reason or another you’re not getting jobs and have to carry on anyway somehow.

How long have you been sailing Kurt?

I started late in life. I’m 82 now, so I’ve been sailing for 40 years now.

How did you begin sailing?

Kurt: Now that’s a story. When I first came to Sydney and we started the company here we were mainly looking after oil companies: Service Stations, Oil Depots painting and maintenance. I was told by our Melbourne boss that most of the State Managers of BP, Ampol and Caltex were all members of the Royal Prince Alfred Yacht Club or the Royal Motor Yacht Club – he said ‘you have you join these cubs’ he said.

I said, ‘alright, I’ll join’.

In those days, for me, being on the water would have meant having 150 horsepower behind me to propel me forward. I had an office in Rydalmere then and in Victoria Road was where they had all the boats for sale on display at the various boatyard outlets. I would often stop and look at them and think ‘these are something’.

As it turned out though, most of the guys I met through the oil companies were sailors, not powerboat people, and they would take me sailing.

For instance, Sir William Walkley, I was lucky to become very friendly with him. We actually did a job on his place where I had a little accident and he ended up laughing his head off over it and nicknamed me ‘the little German bastard’. He would ring up and say ‘Kurt, what are you doing tonight? I’ve got people coming and I want you to come too.’

I would answer, “I’ll be there Sir William.’ And he’d say, “don’t call me Sir William, call me Bill!’

Through him I met people such as Arthur Ash, the first indigenous tennis player and many other very wonderful people. He had a boat and would take myself and my wife and other people out. The guy from BP was a known sailor too and a member at the RPAYC, he too took me on board.

The first chap to take me out was the then State Manager of Olympic Beaurepaires, Jim Birdsler. On one sail he was talking to my wife Hilde and said ‘Kurt, take the helm!’ and I did so and he said ‘oh, you sailed in Germany then?’. When I explained that I’d never been sailing he said I ought to get myself a sailing boat, ‘you have got a bit of talent there.’

I thought he was having me on but from there that idea developed.

We bought our first boat, Dulcinea, named after the Don Quixote character.

This was a very comfortable boat but ask my son…it didn’t sail…

Robin: No, we couldn’t sail.

It was a twin keel big flat deck thing. I remember when we picked it up from Castlecrag, it was a disaster. We went out on the other side of the Spit Bridge, we’d never sailed before, it was just me and dad, got out there in the middle and it was blowing a good nor’easter, and we were on our ears. He’s screaming, I’m making coffee, and we actually turned back…

Kurt: That was the first attempt. The second attempt was not much better. I got worried, again the boat was going (describes tilting adversely with his hands)…

Robin: …It was madness…

Kurt: …and then I saw a small dinghy there with some Italians, they had about that much freeboard (shows two feet), and they were fishing! I thought, ‘if they are safe we are safe’.

We brought it back to Pittwater, we were fine.

Robin:(drolly)…yeah, but it took 8 hours….

Kurt: but that’s how I learnt how to sail. Although I was practically forced by the company ‘you are running the show here, you have got to get close to people, that’s the way to do it – go sailing’.

But really, from that day on, that was it…

You fell in love with it?

Kurt: (shrugs) yes, that was it. I still love it.

Sailing fully occupies you – there’s always something to do on the boat, always something to improve. It’s an all-embracing hobby.

Do you think you’ve grown as a person through sailing?

Kurt: No, I think it’s the opposite. You get impatient and you start screaming.

Robin: you do get to learn a lot and this settles your sailing down a bit.

Kurt: No, you do all those things to cover up your own shortcomings as a sailor.

Robin: The more they scream, the worse they are as sailors.

Kurt: A good sailor is very calm. A good Skipper is just ‘do that’, ‘do this’…’that was wrong, do it again’… very calm the whole time.

Robin: A good sailor anticipates what their crew may do and what the conditions will be. They brief the crew; ‘ok, we’re coming up to the mark, we’re going to drop the jib and turn this way’…

Kurt: but if you haven’t got that you cover yourself with screaming at them that they’re getting it wrong.

So you’re a calm sailor Kurt?

Robin: no, he screams. You can hear him form one side of Pittwater to the other. People can hear him coming.

Kurt: Yes, I cut loose.

Are you the calm sailor then Robin?

Robin: well, he screams so much I decided that I’m not going to scream, ever.

(Kurt laughs.)

Robin: I’ve got a good crew as well, it just works like clockwork and works fine.

You have another boat now don’t you Kurt?

Robin: yes, he sold his old one and said ‘I don’t know whether I’ll get another boat’. I said, ‘well, you can still sail, you better buy another boat because you’re not going to be happy sitting out there watching everybody else go past your window on Saturdays and pine for sailing.’

So I got him a really quick one which is a pain in the a*se because he beats me. I gave him this little crap sail I found because I felt sorry for him and then he beats me with it. I’m spending thousands on gear and I found one on the side of the road for him and he beats me with it!

Yesterday I was about a kilometre in front of him and he still beat me.

Kurt: Yes, that’s a good sail. He found it on one of those council cleanups, said ‘can you use this?’…’yeah, maybe’.

We’re developing a new concept out of this now.

Robin: I’m not giving him anything in the future. Nothing.

Right: Celebrating the German heritage

So you have Lukim Yu?

Robin: yes, which is pigeon English for ‘See you later!’. I didn’t name it this – it was named it up in Queensland. I got this trimaran 10 years ago now.

Kurt: he had it up in the paddock at Terrey Hills for three months fixing it up.

Robin: When I first brought it down it need around three months work on it, it needed new systems. We just opened it all up and changed it. I knew as soon as I put it in the water it would be a pain in the a*se to do anything with it, it just wasn’t functional.

Kurt: He changed everything on it.

So you did all that yourself?

Robin: Yes.

So you have learned a lot more than you knew when you started through sailing?

Kurt: Sailing is common sense.

Robin: It’s being practical.

Kurt: You have to look at it and think ‘what’s the easiest and safest way of doing things?’. If you work on the basis you will be fine.

Robin: Before you drill a hole you think about it, think about it overnight. You see a lot of boats with holes drilled all through them and know it doesn’t work, it’s horrible to see that.

What’s the longest sail you’ve been on?

Robin: I did a Brisbane to Gladstone about five years ago on a 42 foot catamaran. That was pretty wild, a really big swell – at three o’clock in the morning you’re jumping out of your bed.

I’ve done lots of sails up to Lake Macquarie in 50 knots too.

I’ve turned over two boats here too (in Pittwater).

Dad hasn’t turned one over yet.

Kurt: No, never. That’s the bottom line with a multihull, whether a catamaran or trimaran; they’re great boats but they do go over. With a multihull boat if you get a knockdown you come back up again. With keelboats you can get a knockdown and then they take water and sink. With a multihull, a catamaran or trimaran, they can go completely 180º and you are still safe; you can get on the other side, on the trampoline, and you’re safe.

When things go wrong

Is that why you both chose Multihulls?

Kurt: No, it’s the excitement, it’s the speed. When we do 10 or 12 knots you look around and think, ‘what the bloody hell is wrong today; why are we going so slow?’ whereas this may seem fast on a monohull.

We’re doing 20 knots +.

Robin: We were doing over 20 knots on Saturday going down and 12 knots up against the breeze. They don’t lean, they’re always flat, so it’s like skiff sailing, they’re like a sports car.

Kurt: it’s fantastic – you have got to be alert.

Robin: When we take a mono guy on our boat we have to warn them about the speed because when we get going they can actually fall over with the inertia as they accelerate so quickly – it’s a different kind of sailing.

Will there be some rivalry at this year’s Lock Crowther Regatta between you two?

Robin: Always. There is every Saturday.

Who is the best sailor then?

Robin: Dad is, he’s older. He panics when trying to get in front of me, and can do a few dumb things then. He gets flustered and starts waving around.

Saturday is a good instance – we got in front of him and then he tacked out there for some reason.

Kurt: on the windward run, near Longnose?

Robin: yeah

Kurt: I didn’t want to get into the shadow of Longnose.

Robin: but then you went all the way into Towler’s.

Kurt: Yes, we overlaid it.

Who is on your crews?

Kurt: The partner of my daughter. He’s been sailing about three months and is really trying hard.

Robin: on my crew I have an English girl, Estelle, who had never been a sailor before, and she is awesome.

What’s it like being part of the RMYC Multihull Division?

Kurt: It’s great. All of the RMYC Divisions are very friendly, and it’s a great club to be a part of.

Robin: there’s friendly rivalry but everyone is aware that because we’re going so fast we’re very very conscious of avoiding others out on the estuary, or wherever we’re sailing. The bottom line is the whole Division has as its base ‘avoid collision at all costs’ – we’re aware that people don’t realise that we may look like we’re at the end of the estuary one minute but two minutes later we’ll be on top of them, so we sail accordingly – safety first.

What is your favourite place in Pittwater and why?

Kurt: I have no favourite place, the whole of Pittwater is wonderful. Pittwater can be nasty in certain winds, when there’s a westerly, you have to know what the hell you’re doing. When that westerly is on you have got to be really alert; without warning the wind will come over the top, you can’t even read it on the water, it’s just boom down on top of you and hits you with full force. I wouldn’t like to live anywhere else though but here.

Robin: A lot of people don’t like sailing on Pittwater because the wind shifts can be challenging, you get a lot of bullets with the high hills, and some people have nicknamed it ‘Sh*twater’. Some people prefer the big open water where they can do a 5 kilometre kite run, but sailing here makes you a better sailor. You can tell who are the Pittwater sailors, they’re always on trim, whereas if they’re from the harbour they’ll sit back on the rails. Bottom line is, the world’s best sailors, people like Spithill, they grew up sailing here. There have been heaps of world champion sailors come out of Pittwater – too many to list or name.

What is your ‘motto for life’ or a favourite phrase that you try to live by?

Kurt: Enjoy life as much as you can. When I was a lot younger all the people said ‘enjoy your life because life is short’. I didn’t know what the hell they were talking about because in those days, and that time, a week was an eternity.

But now I can see one year after the next and that it goes and goes and goes.

The most important thing is that you stay fit, you stay as healthy as you can be, and enjoy your life.

Robin: That would be the same for me too. Also, be gentle on yourself.

Kurt: You see, he recently became a grandfather and I recently became a great grandfather.

Robin: which is a great reminder how your kids and your family are the most important thing in your life. You don’t want to be the richest man in the graveyard, do you – if we thought that we wouldn’t have boats!

Notes

Post World War II Migrant Ships: Castel Felice

The Castel Felice ventured to Australia as an immigrant ship on a total of 101 voyages between 1952 and 1970, carrying over 100,000 immigrants to Australia and New Zealand. She was commanded by an Italian crew and carried passengers from many different countries including Italy, Germany and Britain. Many passengers remember the rough seas and shabby state of the aged ship with apprehension and delight.

Facts at a Glance

Dimensions: 493 x 64 ft (150.3 x 19.6 m)

Registered Tonnage: 12,478 tons gross

Service Speed: 16 knots

Propulsion: Reduction geared steam turbines / twin screws

Shipping Line: Sitmar Line (Società Italiana Transporti Marittima)

History of the Ship

Originally named the Kenya, the immigrant ship Castel Felice began her life carrying passengers and cargo between India and Africa for the British-India Steam Navigation Co.

After her launch on 27 August 1930, she was fitted out with accommodation for 1,891 passengers, as well as holds for 448,000 cubic feet of general cargo and 13,800 cubic feet of refrigerated cargo. Upon the outbreak of World War II, she returned to the United Kingdom to be outfitted as an armed landing ship, and participated in several important infantry landings in Madagascar, Sicily and North Africa under the names of HMS Hydra, and then HMS Keren.

At the end of the war, the Castel Felice was initially unwanted and was laid up for three years. Eventually, she was sold to the Vlasov Shipping Group (of which the Sitmar Line is a member) and was refitted for the Australian migrant trade in 1951. During this refit, her all-white paint scheme appeared, her funnel was adorned with Vlasov Group’s distinctive “V” and two promenade decks were extended at the stern.

Immigrant Ship to Australia

Before departing from Genoa on 6 October 1952 for her first journey to Australia, she was christened Castel Felice. She arrived in Melbourne on 7 November.

Between 1952 and 1955, the Castel Felice made only three voyages to Australia (but many to the Americas) before again being refurbished. The new refit offered many conveniences including a small number of first class cabins, air conditioning, a swimming pool and large public rooms. But for the tourist class, things were still cramped. Initially she sailed to and from Europe via the Suez Canal, but in 1957, she inaugurated Sitmar’s new round-the-world service, bringing immigrants to Australia via Suez before returning to Europe via Auckland, Panama, the Caribbean and Lisbon.

Passenger Experiences of the Journey

By the time the Castel Felice entered the Australian migrant trade at the age of 22, she was already an old ship. The refits conducted by the Sitmar line helped to improve her appearance and onboard conditions, however, as most of her passengers were government-assisted migrants, her accommodation remained very basic.

Wolfgang Kahran migrated from Germany in 1960:

'As far as we were concerned, the Castel Felice was already in the scrap yard. The crew tried their best, but the ship was unsteady. We were eight men in a double cabin – four tiered bunks! There were no luxuries for us.'

Axel Scholz migrated from Germany in 1958:

'Aboard, the fact the family was not to be together was a shock. My father and I were segregated to a lower deck. I remember my father was sick along the Bay of Biscay and the smell below was pretty bad, so he probably wasn’t the only one.'

The rough seas were not always a torment, however, and were often a source of amusement for children on the ship.

Barbara Scholz migrated from Germany in 1958:

'Sometimes at mealtimes the sea was so rough that the dishes moved on the table from side to side, this was a cause of great delight for my brother and me.'

Her Final Voyage

After such a long and colourful life, the Castel Felice was retired at the end of 1970 as the Sitmar Line’s assisted immigration contract had come to an end. The Castel Felice, too, came to her end – bound for the shipbreakers in Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

Castel Felice 1970

Post war migration: Bonegilla

Australia was experiencing a desperate shortage of labour at the end of World War II. Substantial population growth was considered essential to the nation's future - it was required for economic development and to defend the country against possible invasion. In 1947 Arthur Calwell, Australia's first Minister for Immigration signed an agreement with the International Refugee Organisation (IRO) to allow Displaced Persons from war torn Europe to come to Australia. This marked the beginning of the mass emigration of non-English speaking Europeans and represents one of the largest demographic changes in our history.

Between 1947 and 1953, over 170,000 Displaced Persons came to Australia, mainly dispossessed or homeless Poles, Yugoslavs, Latvians, Ukrainians, Hungarians, Lithuanians, Czechoslovaks, Estonians, Russians, Germans and Romanians. They were culturally diverse, and Minister Calwell called the arrivals 'New Australians'. The press dubbed them 'Calwell's Beautiful Balts,' irrespective of their nationality.

The largest migrant reception and training centre, Bonegilla Migrant Camp received and processed more than half of the 170,000 Displaced Persons. Established on the site of a former army camp, Bonegilla's major functions were to process and house migrants, find work for new arrivals and most importantly, provide language and civics training. The focus of the camp was to train migrants in Australian values so that they could become model citizens.

Bonegilla was the longest operating migrant centre in Australia, finally closing its doors in 1971 - by which time over 300,000 people had passed through. It is estimated that today there are over 1.5 million descendents of Bonegilla migrants.

Bonegilla today

Block 19 is located 10 kilometres northeast of Wodonga at Bonegilla. An interpretation centre, The Beginning Place, is open to the public daily from 9.30am to 4.30pm. The Bonegilla Collection is located in the Albury City Library Museum.

"Dulcinea del Toboso" is a fictional character who is unseen in Miguel de Cervantes' novel Don Quixote.

Don Quixote describes her appearance in the following terms: "... her name is Dulcinea, her country El Toboso, a village of La Mancha, her rank must be at least that of a princess, since she is my queen and lady, and her beauty superhuman, since all the impossible and fanciful attributes of beauty which the poets apply to their ladies are verified in her; for her hairs are gold, her forehead Elysian fields, her eyebrows rainbows, her eyes suns, her cheeks roses, her lips coral, her teeth pearls, her neck alabaster, her bosom marble, her hands ivory, her fairness snow, and what modesty conceals from sight such, I think and imagine, as rational reflection can only extol, not compare." [Volume 1/Chapter XIII]

In the Spanish of the time, Dulcinea means something akin to an overly elegant "sweetness". In this way, Dulcinea is an entirely fictional person for whom Quixote relentlessly fights. To this day, a reference to someone as one's "Dulcinea" implies hopeless devotion and love for her, and particularly unrequited love.

Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dulcinea_del_Toboso

.jpg?timestamp=1474509460458)