April 30 - May 6, 2017: Issue 310

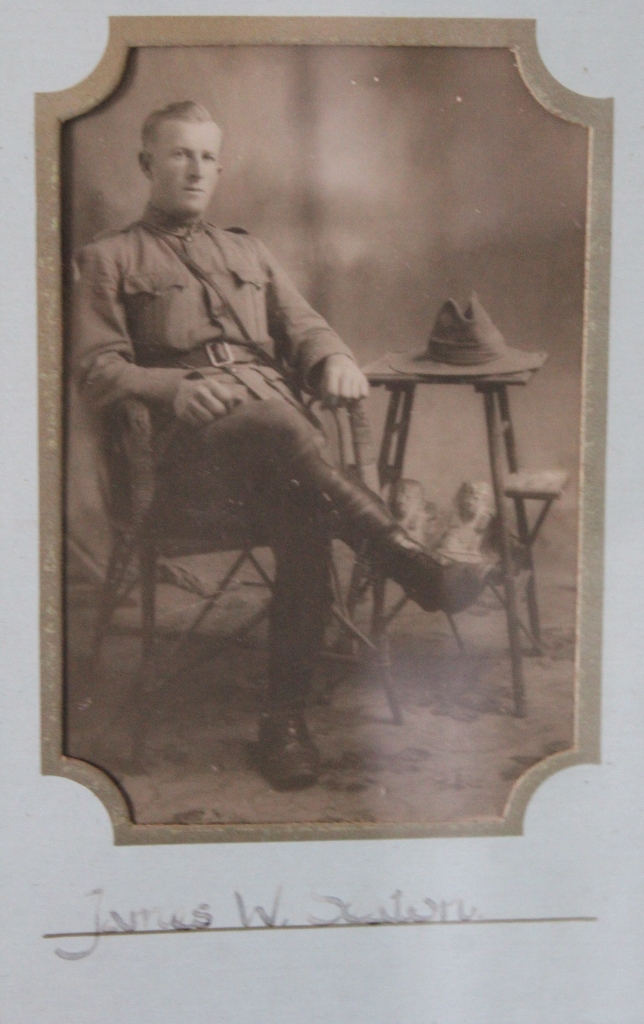

John Seaton MBE

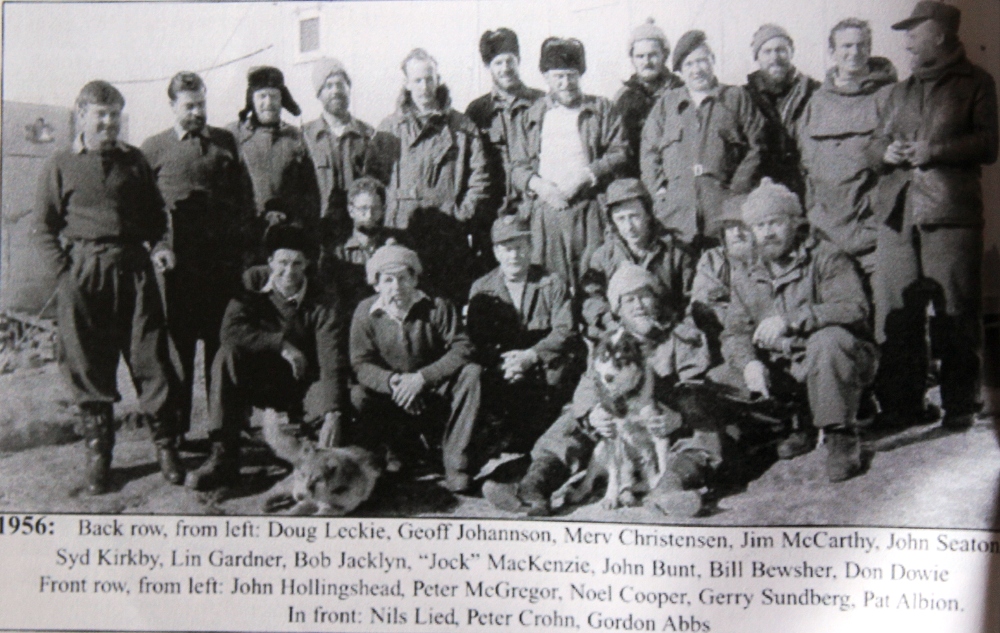

John Seaton MBE, Avalon Beach RSL Sub-Branch member, served in Korea in the Royal Australian Air Force. He set up air strips and routes in the Solomon Islands, establishing an airline, and had the honour of finding the biggest glacier in the world in Antarctica, prior to that, in 1955, subsequently named the Lambert Glacier after the director of national mapping in Canberra. There is also a Seaton Glacier named for the gentleman himself.

Born in Launceston, Tasmania on April 21st 1927, John's wife Barbara, when we asked her why he had done so many amazing things, reasoned he was one of those amazing adventurers born at a time and on the cusp of when finding unknown things, like glaciers, or doing things that needed to be done, like starting airlines for isolated places, could still be achieved by those with the right spirit.

Where and when were you born – where did you grow up?

I was born in Launceston, Tasmania on the 21st of April 1927.

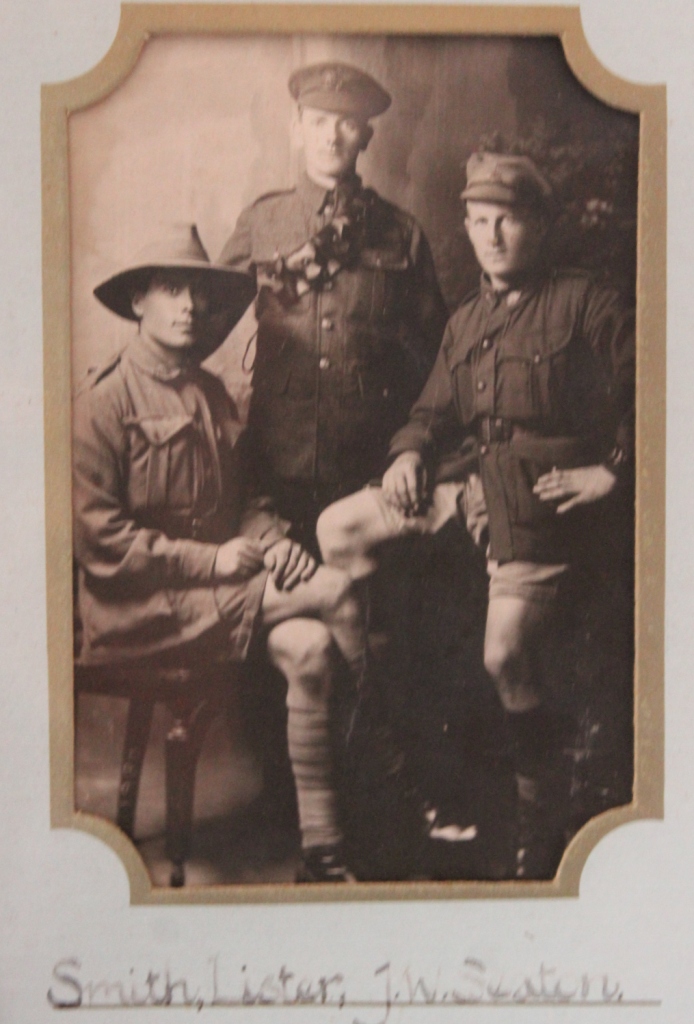

My father was one of three brothers. Alec, aged twenty one died very early in the piece – he was the eldest brother. Col and Dad went to the First World War – Colin was in the 12th Battalion and landed on Gallipoli and then went to France and ultimately he lost his leg through battle there.

Col died around sixty-five I suppose. Dad was in the Light Horse, the 1st Light Horse, and he saw action all the way up through Palestine, it was called in those days, and into Syria, through Beersheba – you’ve heard of Beersheba no doubt – the big charge and everything up there. He ended up in Damascus and came home at the end of the war from that area.

Did your Dad ever talk to you about his war experiences?

Did your Dad ever talk to you about his war experiences?Only a little bit, and only the funny things – he liked to talk about the funny things.

I remember he was with his mate one day, and they were both on horseback. He drank all the water that he had in his canteen before about eight or nine in the morning, but he was able to get half a bag of oranges, and he ate oranges all day. He said he was in such a state that night that it was very laughable.

Or he spoke about his times in Cairo. I remember he was a great photographer, had one of the first of the bellows type Kodak cameras, and he took that with him everywhere he went.

He had a little business running at one stage, he told me, where he’d take all the pictures out in the field – incidents that you’d see from day to day in the horse lines, or wherever they might be. He’d get them down to Cairo as soon as he could, get them developed and processed, and then he’d make a big sale in the next week or two when they came back.

He started a carrying business in Launceston when he came home, had four or five trucks at one stage, and he was in transport so I got to know vehicles pretty well, of course and learnt to drive pretty early in my life. Dad was in a position where he was able to send my two sisters and myself, to private schools.

He continued on in the carrying business, in the transport business until he was about sixty five. He sold the business and he retired to West Launceston, and he was a great gardener, and he gardened on for the rest of his life, and he died at the age of eighty seven I think it was.

He was a firm character, heavily involved in RSL [Returned and Services League] matters in Launceston, and did quite a lot. He was the secretary of the branch in Launceston, and involved in many other organisations too; Red Cross, was the president of the Launceston Football Club at one stage.

He almost became a councillor on the Launceston City Council at one stage but missed out by a few votes there.

What was your mum like?

Mum was one of those grand old ladies, very Victorian, very prim and proper, a very stately, good looking woman.. She was one of two, Esther Boyd, and her brother Jack was in the First World War. He was in France and he got right through, although wounded quite a few times. But he was one of the lucky ones, and he came back.

Mum married Dad in 1925. She brought us up pretty well I think. I had two sisters and she thought the world of them, and me. I was the middle one. She was involved heavily in the Red Cross in the Second World War, in fact she was almost eight hours a day at that from time to time. Everyone loved Mum.

Where did you go to school?

I started school in 1933 at Launceston Grammar School. I was there until 1945 and learnt to play footy, row, tennis, cricket – after I continued to row with the Launceston Rowing Club. Then I became a coach and also played a bit of amateur league football for Launceston. I was in the school cadets of course, for about four or five years, and they were through the war years mainly – I turned eighteen at the end of the Second World War. I used to enjoy the cadets at school, and I became the best shot in the cadet corps, and won what was called the McLeod Trophy. If I had been a couple of years older I think I would have joined the army during the war. I wasn't inclined towards the air force at the time.

At school we had half a dozen fellows doing extra work, maps and so on, that sort of thing through the training corps and they were heading towards the air force. I thought then, ‘I’ve got to do all that work just to become a pilot’. I could see that the war was running down and I'd miss out on that. So I forgot about that for a while, but I always had an interest in things military. In fact I love marshal music.

What was Launceston like then?

Launceston was a small tow, but very industrialised. In fact I was only talking to a friend of mine the other day and we were comparing notes on the things that we don’t do in Australia now, that we used to in the old days where we had woollen mills, where we used to scour wool, and we used to spin wool, and we used to make woollen products from the same product. Waverly woollen mills I remember made the best woollen blankets in Australia. We had foundries, the railway workshops, could make a whole train. They don’t do that sort of thing anymore, in fact during the war it became an armaments factory more so than a locomotive manufacturing facility, or rolling office facility. They were making shell cases and turning out various other components for weapons in the railway workshop.

There were only forty thousand people in the town when I remember it. Hobart was always the big town in Tasmania. Launceston was a small well put together little town, in fact we had ships coming in and out of Launceston in the early days, ten thousand tonners coming up to Launceston, which meant they’d dredge the river quite a lot.

What do you recall about World War II?

Dad was disturbed by it all because he’d been in the First World War. When the mobilization came most of the young fellas around town started to join up. Dad’s head driver, Col Davies, joined almost the next day, and he went down to Brighton camp in the south of Tasmania near Hobart. The next he was in the 9th Division and heading towards Egypt. He went through most of the action up there. All his other drivers ultimately ended up in the services, so he was always looking for new men, and the average age became higher, or they were not suitable for military service. I remember the air raid precautions, things like the Red Cross, and Mum working for the Red Cross. There was the Comforts Fund, it was called the Comforts Fund and everyone got involved in that.

So there was lots of activity in that respect, even in a place like Tasmania, which is pretty much out of the action, but there was a lot of support coming out of Tasmania. There were two or three army camps down there, the flying training base at Launceston, at Western Junction. There was a naval facility in Hobart, a pretty minor one, but I remember going to Hobart one day in the middle of the war to see the Queen Mary arrive there. It was all a big secret but all of Tasmania knew that the Queen Mary was in Hobart, and it was there with troops on board. It was forced down there because of a bit of submarine activity up the east coast of Australia and in other parts, and I think it just decided to lay low there for a little while. There were streams of people heading to Hobart to see the Queen Mary.

Tasmania, possibly more than in other parts of Australia, was very, very British in those days. In fact, some of the songs that we used to learn in school and were taught to sing in the early days, were very pro-British, pro-Empire sort of thing – “The Land of Hope and Glory” stuff, you know, that was there. Most children could sing a British oriented song, more so than “Waltzing Matilda” perhaps. It tended to push that line more so than the Australian line, or the Australian composed songs, or music.

Tasmania was in many respects a ‘land of the gentry’, and it remained that way until probably the Second World War. I wouldn’t say they were landed gentry, but they were very similar to that – they had very, very fine houses on their properties. There was a lot of that, a lot of old families that kept doing their best for Tasmania generation after generation.

One of my Dad’s drivers was in the Mediterranean on a destroyer early on in the piece, and he used to write letters to us from time to time. I thought, ‘Oh, this seems pretty good, I’d like to be involved in that sort of thing.’

The other part was the fear though, I was always a little bit fearful of the outcome of the war, like a lot of people were. Mum and Dad used to talk about it, but particularly when the Japanese bombed Darwin, and we had the attacks on Sydney Harbour. It all became more fearful, and working out what we’d do, whether the whole of Australia other than Tasmania might be occupied by the Japanese, and we’d all be down there as an island fortress. There was always that fear of what could happen, hoping that it wouldn’t. But particularly after the Malayan campaign and the British were pushed out and the guns were pointing in the wrong direction. Things were pretty grim in those days.

We were in the cadet corps and we all thought it would be good if we got straight out of this and into the army now. But we were all lads of fifteen and sixteen, it was just a bit too early; you had to get your parent’s consent to join up.

I got involved in the air raid section of it in Launceston, the Civil Defence, and was a messenger rider on my bicycle. I had a blue armband. They had practice air raids, and everyone had a slit trench in the back of their yard in those days, but they’d quickly fill up with water – I remember that well.

On a particular day they’d have a practice air raid in Launceston, and sirens would go. The place would black out and we’d have headquarters in every suburb, there’d be an air raid warden, we all had a steel helmet – pretty heavy for a bloke about fourteen or fifteen. We would have to ride probably five k’s from this particular headquarters in the suburb, to the central headquarters in Launceston to deliver a message by hand. We didn’t have all the radio communication and all that sort of thing, but we had all that sort of activity going. You had to learn how to put out an incendiary bomb – everybody had a sand bucket and a shovel - all this sort of stuff.

When did you first take an interest in aircraft and aeroplanes?

It was around the early ‘30s. I remember going out to the Western Junction, which was Launceston airport, and this was a flying school in those days. Odd aircraft would fly across from Melbourne to Launceston – there was no runway, it was just grass. This became an elementary flying school in the Second World War, but earlier in the piece, just before the Second World War I remember Dad taking me out to the Western Junction and I had a flight in a Fox Moth with Charles Martin. He was an ex-First World War pilot, and I had a joy flight around the airport and back again; it was only twenty minutes.

I also used to make lots of model aircraft, and in association with a good friend of mine, we’d make soaring gliders and eight foot wingspan and things like that. So even though I didn’t get the opportunity to join the RAAF [Royal Australian Air Force] in the Second World War, but I was always very keen.

What did you do on leaving school?

I was on the trucks with my father for a while. In 1948/’49 I was stricken with pneumonia and pleurisy and hospitalised for several weeks; I went sailing immediately after a regatta, the last regatta of the year in Launceston, and I was out in this boat this weekend, and it was very cold I remember. On the Monday I didn’t feel very well and ultimately I was diagnosed with pleurisy and pneumonia. In those days they didn’t have antibiotics so dealing with things like this weren’t so easy.

It was decided that I should go to a warmer climate, which was up in Queensland. I went north with a friend of mine, Bob McHearn. That was in the middle of the old coal strike in ’49, and we were having power strikes, and there was no beer and there was no this, and there was no that.

In 1949 we ended up in Brisbane. I looked in the Courier Mail one morning and there was this advertisement by the Shell Company, they wanted two people – one for Moresby and one for Rabaul to do fuel management duties in the installations in those two towns. It involved aircraft refuelling and how to control fuel stocks in depots and all that sort of thing.

I had to do about a months training at Bowen Hills with Shell, and then went onto the plane and up to Rabaul. It took three days to get to Rabaul in those days, it wasn't one of those direct services to anything like that. You had to fly through Brisbane and Townsville and Moresby and Lae, and ultimately into Rabaul on DC3 [bomber] type aircraft.

I took a contract for two years up in the islands. Rabaul just after the Second World War was interesting, you could see the devastation in the town and the amount of material that was there after the Japanese were forced out of the place, or forced to surrender. Rabaul had been bombed to blazers by the Allies despite being a fortified town. It had air raid shelters two foot thick all around the main street, going down underground, tunnels dug into the hillsides to conceal military supplies. Lots of ships in the harbour sunk, and around the beaches. Landing barges were everywhere, broken aircraft, rusty galvanised iron – there was a lot of that. Not much was left standing after the war in Rabaul. The only two places that I can remember were still there, was the Burnsville old building, which was just a concrete shell, and the Commonwealth Bank. There wasn't much left of it either, other than the strong room

When did you join the Royal Australian air Force?

I applied to join the air force when the Korean War started in mid 1950 while still in Rabaul. We had quite a number of ex-servicemen in the town who fought in the Second World War who volunteered immediately. They joined what was known in those days as K Force [Korea Force]. They were one of the first battalions that went up to Korea in the Australian Army, to reinforce the blokes in the occupation out of Kure.

I wrote a letter, indicating I would be back in Australia in about six months time, I think it was, and they replied, “We’ve got your application here but you’ll have to renew the whole thing when you get back.” because you still had to be interviewed.

I came back on leave at end of 1950, to Tasmania, and was having a ball learning to fly.

Were your family concerned when you told them you were signing up?

Mum could have been but she didn’t show it. All the time I was in I think she had concern, and she used to voice this to her friends at times I think, but I never knew about it then. It’s only in later years that I learnt that she was a bit concerned about it, particularly when I was in Korea. I am John Seaton and there’s another John Seaton that was going to Hutchins School in Hobart, we used to play football against each other from time to time. He joined the army, went to Korea and was killed. This appeared in the Launceston papers one day, that John Seaton was killed in Korea. It wasn't a headline thing but it was there, it was published, and until that was sorted out it was quite a worry for her. Geoff Stephens, a young bloke from Launceston, joined the air force before the Korea War and he was killed in Korea. Mum and Dad used to enjoy going out with his parents prior to that.

I signed up at Archerfield in January 1952. From then on I did a full year of flying training, the whole of 1952 at Archerfield at what’s called the elementary training school. It was mainly academics at Archerfield and about twenty hours of flying on Tiger Moths, and after three months when that finished we were sent down to Uranquinty, near Wagga, into the advance flying stage onto more Tiger Moths and Wirraways – a heavier type aircraft.

At the end of ’52 we proceeded to what’s called the operational training section at Williamtown, where you start to fly Mustangs, Vampires, that type of aircraft. You have to make certain grades all the way through, otherwise you will fall by the wayside and you're out.

SAW THEIR SONS RECEIVE 'WINGS'

TASMANIAN mothers and their sons at R.A.A.F. station, Point Cook, after this week's graduation parade of 30 trainees, who passed out as sergeant pilots and received their "wings" from the Chief of the Air Staff (Air Marshal Sir Donald Hardman). From left: Mrs. Banfield, of Latrobe, Mrs. J. W. Seaton, of Launceston, Sgt./Pilot G. A. Banfield and Sgt./Pilot John A. Seaton.

SAW THEIR SONS RECEIVE 'WINGS' (1952, December 11). Examiner (Launceston, Tas. : 1900 - 1954), p. 1. Retrieved fromhttp://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article52925416

I graduated out of Point Cook and was posted up to Iwakuni in Japan. The 77 Squadron was based on Iwakuni as far as maintenance and those things were concerned, and if ever an aircraft had to be changed, as far as testing maintenance was concerned it was flown back to Iwakuni, but you were based over at Kimpo or wherever you had to go in South Korea, whichever airfields you based on. In the early days in the Mustangs, you didn’t know exactly where you were going to be the next night really. The next night you could be at an airfield further down the peninsula when you could easily have been based at Kimpo or Pohang or Pusan, or something like that. It all depended on the circumstance because things were very fluid in those early days. The frontline was moving up and down pretty quickly, and things changed quite a lot.

I graduated out of Point Cook and was posted up to Iwakuni in Japan. The 77 Squadron was based on Iwakuni as far as maintenance and those things were concerned, and if ever an aircraft had to be changed, as far as testing maintenance was concerned it was flown back to Iwakuni, but you were based over at Kimpo or wherever you had to go in South Korea, whichever airfields you based on. In the early days in the Mustangs, you didn’t know exactly where you were going to be the next night really. The next night you could be at an airfield further down the peninsula when you could easily have been based at Kimpo or Pohang or Pusan, or something like that. It all depended on the circumstance because things were very fluid in those early days. The frontline was moving up and down pretty quickly, and things changed quite a lot. Iwakuni was not too far from Hiroshima. You were taken in a bus, if you had to go over to Kure to the army establishment just on the other side of the base where we were, at any time. The train ran right through Hiroshima. Nobody worried about radiation or anything like that in those days, it was only in later years that people got a little bit more worried about it, but it was there for the eye to see and completely devastated.

We used to treat the Japanese with respect, it was their country again, even though it was occupied. They were hard working people, and a lot of people in the base were Japanese employed by the air force, the Americans and Australians. I think all those that were there at the time were youngsters and what had happened wasn't their fault. There were a few engineers, Japanese air frame fitters and other technicians that had been in the Japanese air force in the early days of the war, and they were re-employed again by the Australian Air force, the RAAF, in hangar work. They were only allowed to work on some of the menial tasks like aircraft cleaning and polishing. I think that they were still in the mind that they could do something to an aircraft which wouldn’t assist us in our flying capabilities.

What was the squadron base in Iwakuni like?

It was a big place, an old Japanese installation of many hangars, big hangars which were pretty rusty and they were a bit worse for wear over the years. It was also the headquarters for some of the Kamikaze pilots when they did their training apparently. The Australian Air force had control of the whole place, and then the Americans came and they took over Iwakuni and the RAAF became lodgers. That was ok because we still had plenty of space. The quarters were good. The Japanese Air force used to live reasonably well and they built very good accommodations for their men. Rather big buildings with separate and double rooms, common bathrooms with plenty of hot water and very clean and well run. There were good gardens around the area, big buildings and nice dining rooms, and it was very comfortable.

I did the last six months of the Korean War, so I had a pretty comfortable war, you might say in that respect.

I flew forty nine missions over Korea, as opposed to Jack Murray who did three hundred and thirty three missions, which is quite a lot in two or three tours to do that. Everything’s ok in air force flying and operational flying until you get hit – it’s alright until that point you might say. Life in Japan was pretty nice and easy in those days.

Could you outline what was involved in a mission?

You would go down to the flight hut and be there at a specific time, not late, and get your gear on. Sit down, and one of the first briefings would probably be from one of the American weather fellows who would tell you what the weather conditions were like in North Korea on that day. They had very good contacts up there so these were pretty accurate; they’d tell you about contrails in the sky, persistent contrails could be expected, and the cloud cover – any other information that might be interesting for if we were going to do rocket striking. Then there would be our own intelligence fella, he would tell you a bit about the target, distribute some photos and he might say that there was a new flak battery just been established here, and you'd mark that in on your map, because these things used to move around a little bit. With their zero photography and stuff that they had, they could pick this up pretty quickly. The Americans thought it was pretty high tech – it’s better now of course. After that the bloke that was going to lead it has a few words to say, we’ll do this or we’ll do that. Everything is pretty much as it was in the training manual there, once you get to the target, everything is very similar, you get to that intercept point and then you roll in.

John is on left

After the intelligence briefing, at a particular time, you always had a time to take off, because there were so many missions coming backwards and forwards, that you were in a slot to leave at a particular time at the end of the runway. So you had to get to the runway as a squadron of sixteen, to take off at say ten thirty or something. You always had the same plane – I was mostly in number 734, you couldn’t always do that due to serviceability and things like that. So sometimes you’d have a different aircraft, but most times I flew the same aircraft.

You get out to the plane at the appropriate time and you start up, check your radios, make sure they’re all working. He leads out and away you go, sixteen aircraft taxi around the perimeter track, and in fours you line up. Two there and two there. The signal is given and away you go, there’s all these screaming jets and hot bitumen and stones and things right around the plane. You could have eight or sixteen rockets on. So the first four go and then the next four line up – actually there were times I remember when we had the whole sixteen on the runway at one time. But in hot weather it could cook the bitumen up too much, with all those aeroplanes and the jet blaster if I remember the procedure. Anyway it wasn't long before you were in the air and you all form up in battle formation.

You climb to altitude, which on the way was twenty five thousand feet, and that’s where you start to rubberneck and look for things, and flak and other aircraft that is not friendly. Then he gets to that intercept point and in you go. That’s about the way things go. If you were there in the mid-winter, you'd be in your immersion suits - a rubber suit that clasps very tightly down here, and you’ve got boots that seal up against water, and neck ties around here. The only part of you that would get wet would be your hands and your face. So if you're unfortunate enough to be there in the middle of winter you wear an immersion suit. Most of the time I would be in a normal cotton flying suit and a hard hat, or early on the cloth helmet or the leather helmet.

We would fly around twice a day, sometimes only once.

SEOUL, SOUTH KOREA. 1953-09-05. FORMER POW SERGEANT DON PINKSTONE, BEING MET AT CAMP BRITANNIA BY HIS BEST FRIEND SERGEANT JOHN SEATON OF NO. 77 SQUADRON RAAF. PINKSTONE HAD BEEN SHOT DOWN OVER NORTH KOREA ON 15TH JUNE 1953 WHILE FLYING WITH NO. 77 SQUADRON. Image No.: JK0866, courtesy Australian War Museum

SEOUL, SOUTH KOREA. 1953-09-02. PILOTS AT PRESENT SERVING WITH NO. 77 SQUADRON, RAAF WERE ON HAND AT CAMP BRITANNIA TO MEET TWO OF THE RAAF PILOTS WHO HAD RECENTLY BEEN RELEASED FROM PRISONER OF WAR CAMPS IN NORTH KOREA. LEFT TO RIGHT SERGEANT JOHN SEATON; SERGEANT PETER COY; PILOT OFFICER BRUCE THOMSON (POW); SERGEANT ATHOL FRASER AND PILOT OFFICER VANCE DRUMMOND (POW). Image No.: JK0859, courtesy Austalian War Museum

What do you think about war or conflicts now, so many decades on?

That they’re no good – no war is any good. Dad was wounded in the first world war, Col lost his leg because he was wounded at Gallipoli and then they posted him into France where he got trench feet. They took him over to England and sent him home just before the war ended and he ended up having his right leg amputated.

It was sad to see what the war I was in had done to Korea – there were only about five buildings left standing in Seoul. There were little children running around by the thousands with no parents.

However, there was a communist threat at that time, and it was a valid one I think, but perhaps not so much in recent years.

To progress on I can’t understand why they had the First and Second World wars when I hear what’s happening even today. A lot of people are getting hurt while they keep talking about all these ‘maybes’. Putting that in perspective though, the human race has had one conflict after another since time immemorial, some of it based on greed when you consider historical conflicts going back to Alexander the Great, or defending rights, when you consider WWII or Korea.

What was the most horrific experience for you of the Korean War?

I was lucky in that I didn’t get shot up but we did lose four fellows that I knew and 41 pilots all up over the three years of the Korean War, which is a pretty high toll. These were mainly lost from ground attacks up and low level flying anti aircraft.

You were in Korea for three months after the Armistice was signed – what did you do then?

We continued to train and operated most days of the week when we could and it was always a lot of upper air training to be done, and out on the range; gunnery and rocketry, using up old stock of ammunition and things like that. It was business as usual, other than actual combat. You do this to keep your competency and standards up.

What did you do when you came back to Australia?

I had Leave, went to Launceston and then came back over to Melbourne. I’d signed on for six years and they had decided I’d make a good flying instructor. I was posted up to 75 Squadron at Williamtown.

What was the reaction of those at home towards someone who had served in Korea?

In those days it was a bit like after Vietnam. A lot of people didn’t know where Korea was and they didn’t know a great deal about the Korean War. A few people who had been in the services before and people in the RSLs [Returned and Services League] knew a little bit about it. I joined the RSL as soon as a came back and I was accepted with open arms, but there was an attitude in the RSL in those days from the older blokes, “Oh, he’s just been to Korea” sort of business, “That’s only a police action.”

What you also need to take into account is that we all went away in dribs and drabs, and we all came back in dribs and drabs. We never came back as a full squadron and marched down the street or anything like that. There was no grand Welcome Home.

I did some time at home, bought a car and came across to the mainland, was driving around Victoria. While I was over there I got the posting for Sale, where I had to go to the No.11 Flying Instructors Course, Central Flying School and learn how to be a flying instructor, and that the start of two years of instructing, including the time at the Central Flying School.

Then I went down to Antarctica. I spent twelve months there on secondment to what was known as the Department of External Territories in those days. We stayed the whole year – it was the first time anyone had taken two aircraft and a hanger and wintered right through the Antarctic experience.

We were very lucky we were able to keep both our aircraft intact. Used up all our fuel, we did about seven hundred hours of flying between two pilots.

Sabre Conversion Course, Sept. 1957 - John is first on left

I came back from that and I went back to Williamtown in 1957 and I met Barbara, she’s a Newcastle girl.

How did you meet Barbara?

I’d been in Antarctica and was posted back to 75 Squadron at Newcastle. One day I was in the back bar room of the Great Northern Hotel.

Barbara: I used to work every fourth Saturday at the Radiography department in the hospital, which is just up the road, and would meet the friends I’d met at Williamtown at the hotel. This was before I’d met this one. We’d meet there and then go and have Chinese for lunch. I stuck my head through the door and this one was the only person in the place. He said ‘May I help you’, to which I replied, ‘No thank you, I’m looking for…’;Oh’ he said, won’t you sit down…’ and the pick up began.

John: We got engaged on the 19th of December, only eight months later. I then joined Qantas.

When did you get married?

Barbara: John was awarded the Polar Medal and Qantas, who had posted him to New Guinea, gave him a few days off for the Investiture at Parliament House in Canberra. He ran me up and said “could you be ready to be married in three days?’

Barbara: John was awarded the Polar Medal and Qantas, who had posted him to New Guinea, gave him a few days off for the Investiture at Parliament House in Canberra. He ran me up and said “could you be ready to be married in three days?’John: Our first daughter Peta was born at Port Moresby when I was flying for them. Peta did her PhD in archaeology and was a Member of the State Government for six years.

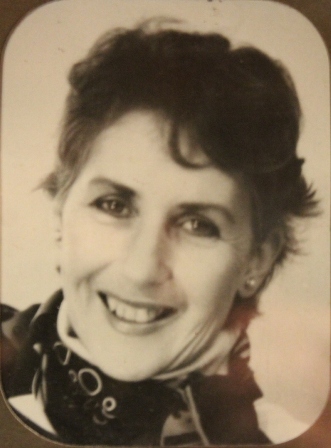

Right: Mrs. Barbara Seaton

I was with Qantas for about six years but it wasn't quite my cup of tea, and I got back into commercial aviation, and ultimately I became general manager and chief pilot of Solomon Island Airways Limited, based on Honiara in the Solomon Islands.

We formed an airline called Solomon Islands Airways Limited, SolAir and it was pretty hard work in the early days. We had to open up lots of airstrips, get better aircraft and get the maintenance schedule working well. This too was still littered with refuse from WWII, there were empty shell cases everywhere, it was still a mess.

Ultimately we ended up with 21 airfields and it became a very fine little airline and in profit. We were there for 8 years. I was flying some of the old wartime Catalina’s up there – amazing long range planes – flew them up on the Fly river too, in New Guinea, for Qantas.

You had to know your tides when stationed in New Guinea. We had a mooring up there. You had to know your tides as when the river’s full it’s time to land and then it starts to run out again. Qantas then got three Otters, which we’d fly out of Moresby. An Otter was more or less a large Beaver, a ten or eleven passenger single engine aircraft still. It was quite pleasant flying up there around the coast and the delta and up and down the rivers, I enjoyed that. They were amphibians too.

I used to like flying up to the three large, freshwater lakes Paniai, Tigi, and Tage. They are located in the Paniai Regency in the central highlands of West New Guinea – a beautiful place.

All the time I was up in the Solomons I enjoyed it immensely. I was awarded the MBE [Member of the British Empire] while I was up there, for services to the Solomon Islands, and the people of the Solomons. I went to an investiture at Buckingham Palace for that, which was very interesting.

What did you wear Barbara?

Well, I had to go to England to buy the gear because all I had was tropical stuff. Fortunately we were there early enough to do that. I had a very plain tailored black dress with roses on it and a very stylish black hat with a pink felt band, the same colour as the roses and a grey overcoat with a fur collar. I bought the handbag and gloves in Scotland and it was a good outfit, suitable. It was November 1975, so it was cool, bit not old.

Sounds spiffy – what was perspective of the experience John?

Well, we’d already met the Queen when the Britannia came to the Solomons on the Royal Tour of 1974 after the Queen had attended the closing ceremony of the New Zealand Commonwealth Games. We had a very lovely dinner aboard the ship, Lord Mountbatten was there, a fine man.

What did the Queen say to you when she gave it to you?

She asked me where I was from, because she had forgotten that she’d met me before. I said I was from the Solomon Islands. “Oh, Honiara, yes I remember being there last year and it rained all the time.” She thanked me very much for my services to the Solomon Islands and pinned the aforementioned medal on my chest.

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry; rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations, and public service outside the Civil Service. It was established on 4 June 1917 by King George V, and comprises five classes, in civil and military divisions, the most senior two of which make the recipient either a knight if male, or dame if female.

The five classes of appointment to the Order are, in descending order of precedence:

Knight Grand Cross or Dame Grand Cross of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (GBE)[a]

Knight Commander or Dame Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (KBE or DBE)

Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE)

Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (OBE)

Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE)

What did you do after the Solomons?

After the Solomons I stayed in Sydney most of the time. I kept going back to the Solomons for a time, to relieve and do flying training for the fellas up there, and endorsements and ferry and that sort of thing aircraft out of Australia to the Solomons.

When did you move to Avalon?

In 1976. I semi-retired out of flying then and did a bit of part time flying on floats out of Palm Beach with Vic Walton for two and a half years. I really enjoyed that, loved it, even though I was only flying part-time.

I even did one right around Australia for a television program called Pelican’s Progress, which was done by Bob Raymond. We had three aircraft and were looking at all the coastlines. It was Reg Morrison a great photographer – you’ve probably heard of Reg – who did that. Ultimately I didn’t fly much more after that because my eyes were really bad then, and I had to give it away.

I spent most of my time involved in a bit of charity work and a little bit of involvement with air force association work. Until now, I’m aged seventy seven and I’ve got a life that’s pretty comfortable still, and I reside here with my wife, and the family are all grown up. I’m a grandfather of five, and here we are talking to you fellas.

What are the three most outstanding parts, for you, of what has been an amazing career?

Well, being involved in the Korean War is certainly something and certainly had some thrilling experiences.

Being part of that Antarctic mission is clearly a stand out too, that was another full year there.

I suppose when you tally all the Solomon Islands stuff up, that would be quite an expedition compared to all the other stuff.

Did you have any inkling of what you had achieved through the Antarctica Mission?

Well, we were among the early birds with having aircraft down there really. You can go right back to Admiral Byrd, the American, and they had taken aircraft down there but had all sorts of problems because they couldn’t hangar them so their aeroplanes would be blown away and wrecked. They did it rough in those early days.

We took a hangar down, which took us about two months to build, but all the other expeditions had helped us with the information in order for us to be able to do that. being able to do this meant we could hangar two aircraft and fly through most of the year apart from a few weeks when it was just too dark in the middle of the year.

We were the first to take aircraft down and survive through the Winter and right to the end of our time there.

In that time we did do a lot of work, mainly exploratory stuff. We had a set of trimetric cameras in the aircraft and you would fly back and forth in the aircraft at 7 or 8 thousand feet. I remember doing a 14 hour day once, in two lumps of seven. All our film was good and they made lots of new maps.

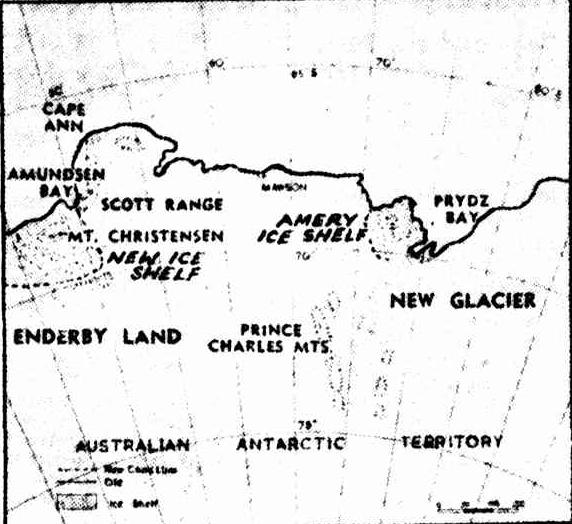

In amongst all that we had an idea that there was an extension to the Amery Ice Shelf , that it had to be glacier fed or that the whole of the continent was subsiding and this throws ice out that stretches all the way round.

I was the bloke who had the opportunity in this magnificent day, when we just had to go on because the day was so great. We found this magnificent glacier, now called The Lambert Glacier.

I could see right over the curvature of the earth it was such a good day; there was no whiteout, which is a common thing down there. But it was such a good day that we could get all these pictures of the glaciers feeding down into the main stream.

This was pretty exciting as it had never been seen by human eyes before.

School maps can't keep up with Antarctic

School maps suffered another blow yesterday when Mr. P. G. Law, director of the Antarctica division of the External Affairs Department, announced a new change in the Antarctic coastline.

"What was thought land was really an ice shelf," he said.

'"Lots of school maps of Antarctica are about 20 years behind the times, anyway, what with constant new discoveries."

Mr. Law announced two new discoveries by the Australian exploring team of 20 stationed at Mawson.

On October 11, Squadron Leader Douglas Leckie, 37, found the ice shelf at En-derby and recharted 100 miles of coastline.

What was thought to be a mountain in the area (Mt. Christensen) was really an island.

On October 12, Pilot Officer John Seaton, 26, discovered a huge glacier 30 miles wide and more than 150 miles long running: into Prydz Bay.

Both pilots are R.A.A.F. men attached to the expedition. They are war veterans, and do their exploring in a Beaver monoplane.

Lucky escape

Pilot-Officer Seaton had a narrow escape 16 days after his discovery of the glacier when his elevator controls jammed on an Auster during a routine flight. He made a forced landing about 150 miles west of Mawson on the brink of an ice cliff, after a violent struggle to prevent the air-craft plunging into the sea. He corrected the fault and flew safely back to the station.

Mr. Law said the next big plan for the expedition was a trek from Mawson to the Prince Charles Mountains for geological and mapping reconnaissance.

A new map of Antarctic territory with dotted lines showing the new coastline. Black line shows the old coastline. School maps can't keep up with Antartic (1956, November 8). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), p. 8. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71764635

World's Greatest Glacier

DISCOVERED BY R.A.A.F. PILOTS

The RAAF's Antarctic Flight returned recently from a winter on the Continent with a list of discoveries that included the world's largest glacier and entire mountain ranges. Flying their single-engined De Haviland Beaver right through the long Antarctic winter, the RAAF men filled in great empty spaces on the world's maps. Each year the ship which takes the relief party of the Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition also carries a fresh Beaver aircraft and a new RAAF party of pilots and groundstaff. This party relieves the group which has been wintering on the Antarctic Continent. On December 28, 1955, the 1956 group sailed from Melbourne in the "Kista Dan" with a Beaver and a little Auster. The RAAF officer in charge of the RAAF Antarctic Flight was Squadron Leader Douglas Leckie, who had won the Air Force Cross for his work with the ANARE, 1954. The second pilot was Pilot Officer John Seaton, who had been instructing at Uranquinty, New South Wales; when he volunteered. (The RAAF does not assign men to the Antarctic, but calls for volunteers.) The little Auster had been useful in 1954; but it had taught the RAAF that there was considerable danger in having only a light "aero club" type of air-craft for a task which required a rugged and specialised type. The Canadians have designed and produced an aircraft speci-ally for work in the Arctic, which has proved to be just right for the Antarctic. The tough and rugged Beaver has a range of 1000 miles and can carry 850 lb. of payload.

On January 5, 1956, S/Ldr. Leckie took the expedition leader, Mr. Philip G. Law, on a reconnaissance of the eastern limit of Wilkes Land on the edge of the French Adelie Land. They found a passage through the pack ice and the "Kista Dan" began her six weeks' reconnaissance of the Antarctic coast. The Beaver was used to secure photo-maps and to land scientists for geomagnetic and gravity observations, survey fixes and other scientific work. After the ship reached Mawson, the Australian base on the mainland, there was no more flying until the sea froze. Before this, the Beaver had been operating with floats. Now she was given wheels and skis, to operate from ice. The first, big job was to protect the aircraft from the 100-miles-an-hour Antarctic gales. For two months the RAAF men laboured to erect a portable hangar. They were directed in the task by the extremely versa-tile doctor with the expedition. Dr. D. Dowie, who had engineering experience. The doctor was also a pilot, so he had the task of standing by with the Auster when the two RAAF pilots were off in the Beaver. If the Beaver had been forced down, or had been unable to take-off deep in the Antarctic — as nearly happened several times — Dr. Dowie would have made the rescue flight.

In March, S/Ldr. Leckie and P/O Seaton flew members of the ANARE staff on short flights to show them the Antarctic terrain. The Beaver was mean-while thoroughly overhauled and test-flown, and by April 19 it was ready. On April 20, 1956 productive flying began with the Beaver. S/Ldr. Leckie flew, south-west over a group of mountain ranges which had never been mapped, and the next day P/O Seaton flew down the Prince Charles Ranges to new territory. These flights proved that mountain ranges unknown to the geographers extended deep into the Continent. The RAAF's work for a year was decided. In April and May the Beaver flew over Enderby, Kemp and MacRobertson Lands and took camping parties of scientists to King Edward VIII Gulf, Scores -by and Stefansson Bay. At some of these locations the aircraft-landed with 44-gallon drums of aviation fuel in preparation for the long-range flights. By the end of May there were four hours daylight a day, but flying continued until May 25. The aircraft was then given a 200-hours inspection and the aerial cameras were overhauled —long tasks which kept the RAAF men busy for weeks. In July the Beaver began scintillometer work over the ice- free areas between Mawson and King Edward VIII Gulf, and the Auster flew in the geologist to areas of interest.

On one Beaver flight, with P/O Seaton at the controls, the tail wheel passed over a tide crack in the ice on landing in a re-mote area. The bulkhead had to be repaired— this was actually a lucky accident. Later heavy landings on rough ice would have broken the previous bulkhead without the strengthening which the RAAF men gave in the repairs.

By late August there was enough daylight for long dawn-dusk flights. P/O Seaton cleared up an interesting mix-up of bays in the Amundsen Bay area and reported many unmapped mountain peaks, a new glacier, and many islands. Already the RAAF men were remaking the maps of Antarctica. Amundsen Bay gave the RAAF pilots exploration work right through October and scientists were flown in for work on the ground. The last big flight of the sea-son was the most interesting, P/O Seaton being the lucky pilot. S/Ldr. Leckie had already noticed a glacier in the Prince Charles Ranges at latitude 72 deg. south and longtitude 70 deg. east. He suspected it was a mighty one. The Beaver took off on the morning of November 28 with its crew of RAAF men and scientists feeling that they were making history. The immediate reason for the flight was actually to try to locate the extreme end of the great Prince Charles Range whose mountain peaks towered to some 10,000 feet stretched beyond the previous flight limits. The peaks tower as high above the ice-mass of the Continent, many thousands of feet thick, as Mount Kosciusko does above the Australian sea-level. This was a dangerous flight, as the Auster could not have reached the Beaver had it been forced down, and anyway the terrain was too rough for safe emergency landing. P/O Seaton returned that evening with reports of a glacier 200 miles long — at least — and 20-30 miles wide, while the mountains skirting it were 6000 feet on the east and 8000 feet on the west. This tremendous river of ice is without doubt the world's greatest. The RAAF men who wintered last year are now back in Australia and enjoying leave. Their replacements are now hard at work on the Antarctic continent, led by Flight-Lieutenant Peter Clemence, who gained his first sight of the region with the relief ship early in 1956. One aspect of the whole affair, which appears humorous to the RAAF in general, is that the most experienced Antarctic pilot in the RAAF, S/Ldr. Leckie, learned to fly in Malaya. World's Greatest Glacier (1957, May 29).The Biz(Fairfield, NSW : 1928 - 1972), p. 19. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article189939953

Isn’t there another one that has been named the Seaton Glacier after you?

(laughs)

Yes, there is, it’s not as big as the Lambert Glacier though.

Which is our favourite aircraft out of all those you have flown?

The P51, that was built by the Americans and then we ended up building them with Hawker de Havilland down in Melbourne – it was just the best fighter at the end of the Second World War. Just about every pilot you ask will say the P51, the Mustang is their favourite plane, that they wouldn’t mind flying it again. They were fast, were able to overcome anything the Germans sent up. These were the planes that escorted the big bombers on those thousands of bomber raids during the Second World War – the could fly as far as Berlin and stay on station for half an hour before it returned to Britain. Prior to that they couldn’t, the escorts would have to turn around with a hundred miles to go. They were a superb flight plane.

Flying with Vic was pleasant because it was taking me back to the saltwater, I’ve always loved my boats, have had yachts, and also he being at Palm Beach meant I didn’t have far to go to fly. I remember flying out to Young and Forbes – and it looks unusual to see an amphibian out in the middle of Australia.

It's a pretty amazing life you have led though John - with a number of firsts - where did that all come from?

John laughs

Barbara: He's a very unusual man and there are a number of people who ave done similar things. But the man we're speaking of is turning 90 this year and a lot of men of this nature are born out of their time - they were meant to have been born when countries were being discovered; they were adventurers and there are not many of such men now, but he belongs in those ranks.

Is he a little like the eponymous Tasmanian Errol Flynn type? - many Tasmanians who leave Tasmania are then up for anything for all their lives.

Barbara: A little like that perhaps. You also find that with people who leave Papua New Guinea, they too are ready to conquer the worlds they find themselves in.

John: I think I've done alright - I'm happy, looking back now, with what has been achieved.

Barbara and John Seaton - 2017