September 24 - October 7, 2017: Issue 331

18th Century Relic Anchored In New Home

19 September 2017

An anchor dating back to when the French Navy explored our coastline will soon be back on display for all to see, NSW Heritage Minister Gabrielle Upton announced today.

The relic from the last voyage of navigator Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse is being returned to public display on the Sydney headland that bears his name.

The anchor’s return to La Perouse is part of a new leasing agreement between the NSW Government and Randwick City Council which will see the precinct, including the State Heritage Listed buildings and museum collection, managed by the Council.

The anchor, which is more than 230 years old, will now be moved from storage at Rouse Hill back to La Perouse where it will be restored before going on display.

“It will now be one of the main drawcards for the La Perouse Museum,” Ms Upton said.

“This is a remarkable piece of our history – it’s time for it to stop gathering dust in a Government storeroom,” Ms Upton said.

The anchor would have been either on board or being used to anchor the L’Astrolabe or Boussole ships in Botany Bay when the First Fleet was also there in 1788.

“It is one of an extremely rare group of objects in public ownership that survived from 1788, the very first days of European settlement in Australia,” Ms Upton said.

This is one of a few things that has survived from 1788 and it will put on display for everyone to see.

The NSW Government and Randwick City Council are working together to conserve the remains of the anchor.

La Perouse Monument and Museum, Kamay Botany Bay National Park, view to Frenchmans Bay - photo courtesy J. Bar

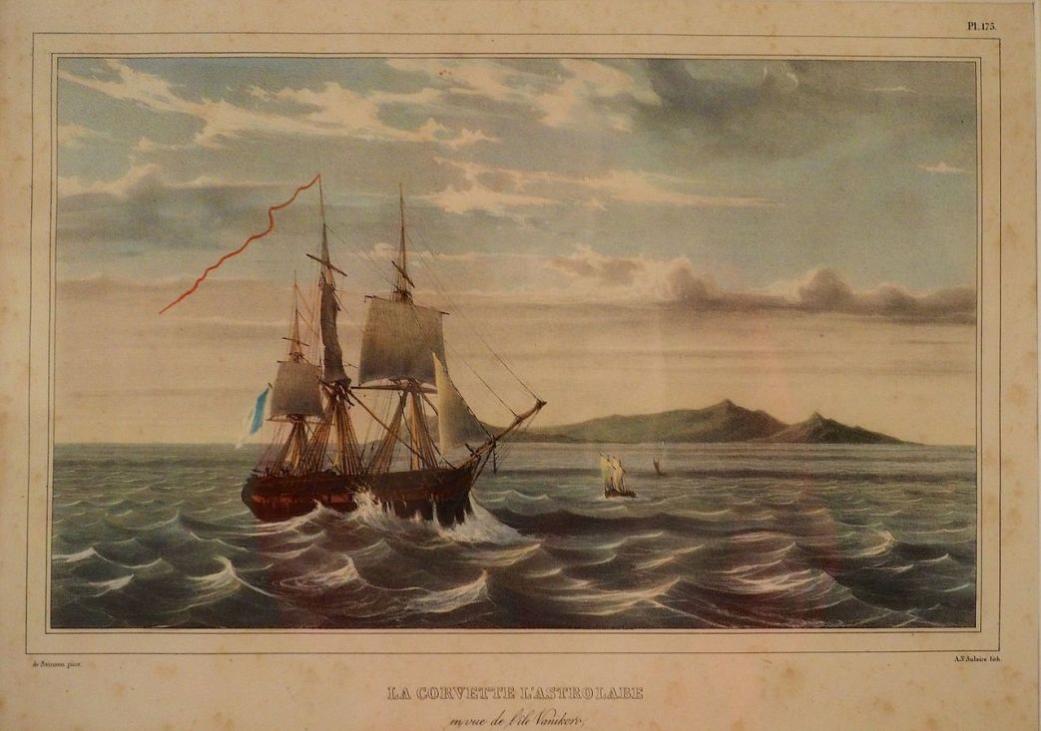

French Ship Astrolabe (1781)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Astrolabe was a converted flûte of the French Navy, famous for her travels with Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse.

She was built in 1781 at Le Havre as the flûte Autruche for the French Navy. In May 1785 she and her sistership Boussole (previously Portefaix) were renamed and rerated as frigates, and fitted for round-the-world scientific exploration. The two ships departed from Brest on 1 August 1785, Boussolecommanded by Lapérouse and Astrolabe under Paul Antoine Fleuriot de Langle.

The expedition vanished mysteriously in 1788 after leaving Botany Bay on 10 March 1788. Captain Peter Dillon in Research solved the mystery in 1827 when he found remnants of the ships Astrolable and Boussole at Vanikoro Island in the Solomon Islands. Local inhabitants reported that the ships had been wrecked in a storm.

Survivors from one ship had been massacred while survivors from the other ship had constructed their own small boat and sailed off the island, never to be heard from again.

The fate of Lapérouse, his ships and crew was a subject of mystery for some years. Louis XVI reportedly often inquired whether any news had come from the expedition, up to shortly before his execution. It is also notably the subject of a chapter from Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne.

Plate from 1833 book showing the french frigate L'Astrolabe near the island of Vanikoro.

Sainson, Louis Auguste de (Life time: 1801-1887) - Original publication: Plate from a book, possibly published 1833

Jean-François De Galaup, Comte De Lapérouse

23 August 1741 – 1788 (?)

23 August 1741 – 1788 (?)Jean-François de Galaup was born near Albi, France. Lapérouse was the name of a family property that he added to his name. He studied in a Jesuit college and entered the naval college in Brest when he was fifteen. In 1757 he was posted to Célèbre and participated in a supply expedition to the fort of Louisbourg in New France. Lapérouse also took part in a second supply expedition in 1758 to Louisbourg, but as this was in the early years of the Seven Years' War, the fort was under siege and the expedition was forced to make a circuitous route around Newfoundland to avoid British patrols.

In 1759, Lapérouse was wounded in the Battle of Quiberon Bay, where he was serving aboard Formidable. He was captured and briefly imprisoned before being paroled back to France; he was formally exchanged in December 1760. He participated in a 1762 attempt by the French to gain control of Newfoundland, escaping with the fleet when the British arrived in force to drive them out.

Following the Franco-American alliance, Lapérouse fought against the Royal Navy off the American coast, and victoriously led the frigate L'Astrée in the Naval battle of Louisbourg, 21 July 1781. He was promoted to the rank of commodore when he defeated the English frigate Ariel in the West Indies. He then escorted a convoy to the West Indies in December 1781, participated in the attack on St. Kitts in February 1782 and then fought in the defeat at the Battle of the Saintes against the squadron of Admiral Rodney. In August 1782 he made his name by capturing two English forts (Prince of Wales Fort and York Fort) on the coast of Hudson Bay, but allowed the survivors, including Governor Samuel Hearne of Prince of Wales Fort, to sail off to England in exchange for a promise to release French prisoners held in England. The next year, his family finally consented to his marriage to Louise-Eléonore Broudou, a young creole of modest origins whom he had met on Île de France (present-day Mauritius) eight years earlier.

Lapérouse was appointed in 1785 by Louis XVI and by the Secretary of State of the Navy, the Marquis de Castries, to lead an expedition around the world. Many countries were initiating voyages of scientific explorations.

Louis XVI and his court had been stimulated by a proposal from the Dutch-born merchant adventurer William Bolts, who had earlier tried unsuccessfully to interest Louis’s brother-in-law, the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II (brother of Queen Marie Antoinette), in a similar voyage. The French court adopted the concept (though not its author, Bolts), leading to the dispatch of the Lapérouse expedition. Charles Pierre Claret de Fleurieu, Director of Ports and Arsenals, stated in the draft memorandum on the expedition that he submitted to the Louis XVI: "the utility which may result from a voyage of discovery ... has made me receptive to the views put to me by Mr. Bolts relative to this enterprise". But Fleurieu explained to the King: "I am not proposing at all, however, the plan for this voyage as it was conceived by Mr. Bolts".

Louis XVI giving Lapérouse his instructions on 29 June 1785, by Nicolas-André Monsiau (1817). (Château de Versailles)

The expedition's aims were to complete the Pacific discoveries of James Cook (whom Lapérouse greatly admired), correct and complete maps of the area, establish trade contacts, open new maritime routes and enrich French science and scientific collections. His ships were L'Astrolabe (under Fleuriot de Langle) and La Boussole, both 500 tons. They were storeships reclassified as frigates for the occasion. Their objectives were geographic, scientific, ethnological, economic (looking for opportunities for whaling or fur trading), and political (the eventual establishment of French bases or colonial cooperation with their Spanish allies in the Philippines). They were to explore both the north and south Pacific, including the coasts of the Far East and of Australia, and send back reports through existing European outposts in the Pacific.

Lapérouse was well liked by his men. Among his 114-man crew there were ten scientists: Joseph Lepaute Dagelet (1751–1788), an astronomer and mathematician; Robert de Lamanon, a geologist; La Martinière, a botanist; a physicist; three naturalists; and three illustrators, Gaspard Duché de Vancy and an uncle and nephew named Prévost. Another of the scientists was Jean-André Mongez. Even both chaplains were scientifically schooled.

One of the men who applied for the voyage was a 16-year-old Corsican named Napoléon Bonaparte. Bonaparte, a second lieutenant from Paris's military academy at the time, made the preliminary list but he was ultimately not chosen for the voyage list and remained behind in France. At the time, Bonaparte was interested in serving in the navy rather than army because of his proficiency in mathematics and artillery, both valued skills on warships.

Copying the work methods of Cook's scientists, the scientists on this voyage would base their calculations of longitude on precision watches and the distance between the moon and the sun followed by theodolite triangulations or bearings taken from the ship, the same as those taken by Cook to produce his maps of the Pacific islands. As regards geography, Lapérouse decisively showed the rigour and safety of the methods proven by Cook. From his voyage, the resolution of the problem of longitude was evident and mapping attained a scientific precision. Impeded (as Cook had been) by the continual mists enveloping the northwestern coast of America, he did not succeed any better in producing complete maps, though he managed to fill in some of the gaps.

He arrived off Botany Bay on 24 January 1788, just as Captain Arthur Phillip was attempting to move the colony from there to Sydney Cove in Port Jackson. The First Fleet was unable to leave until 26 January because of a tremendous gale, which also prevented Lapérouse's ships from entering Botany Bay.

The British received him courteously, and each captain, through their officers, offered the other assistance and needed supplies. Lapérouse spent six weeks in the colony and this was his last recorded landfall. The French established an observatory, held Catholic masses, made geological observations, and established a garden. Their chaplain from L'Astrolabe was buried there and is celebrated annually on the anniversary of his death. Although Phillip and Lapérouse did not meet, there were 11 visits recorded between the French and the English. Over the past 200 years, commanders from the French Navy have regularly paid their respects at the Lapérouse Monument. Lapérouse Day, Bastille Day and the foundation of the Lapérouse Monument by Hyacinthe de Bougainville are celebrated every year.

Yesterday Commodore De BOUGAINVILLE, and all the French Officers, proceeded by land to Botany-bay, where the noble Commodore laid the

first stone of a monumental inscription to the memory of the immortal LA PEROUSE, the north head of that bay being supposed to be the last spot of New Holland on which that great Man touched. FURTHER DOCUMENTARY INTELLIGENCE, RECEIVED WITHIN THE LAST WEEK. (1825, September 8). The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2184418

LA PEROUSE.

La Perouse, or De la Peyrouse, as old histories spell the name, the Telegraph and Custom-house station at Botany Bay, was the scene of an interesting ceremony yesterday morning, the occasion being the celebration of mass near the grave of Father Le Receveur and the monument erected in memory of M. De la Peyrouse. Those who are acquainted with the early history of New South Wales will remember that the french ships Astrolabe and Boussole, under the command of De la Peyrouse, sailed into Botany Bay as the Supply and the Sirius, with their fleet of transports, were leaving the bay for Port Jackson, with the intention of establishing the settlement at Sydney Cove, and that after the departure of the French vessels from Botany Bay, they were not again heard of until a few years ago, when sufficient evidence was discovered to prove that the vessels had been wrecked on a reef in the South Sea, and that all on board had perished. The fate of these French navigators, so long unknown, and the scanty particulars published respecting the expedition upon which they were dispatched from France, have attached a melancholy interest to the incident of their visit to Botany Bay, and have made them conspicuous, not only in the history of maritime enterprise, but in the history of Australia. Two monuments on the slope of a hill overlooking Botany Bay, and not far from the North Head, perpetuate their memory, and the name of the illustrious Frenchman, who commanded the expedition, has been immortalised by being adopted as that of the telegraph station and fishing village that have been established near the spot which, until his fate and that of his companions were discovered, was the last place from which anything concerning De la Peyrouse was heard. The monument erected to the memory of the commander of the expedition is a stone obelisk having an astrolabe (symbolical of De la Peyrouse's ship) on its top, and surrounded at the base by a neat iron railing, which encloses a few pine trees and shrubs. The base of the monument is inscribed in English and in French, the inscription in English being being:—

"This Place Visited By Monsieur De la Peyrouse

In the Year MDCCLXXXVIII

Is the Last whence any Account

of Him

Has been Received

Erected in the Name of France by M.M. De Bougainville and

Du Campier, Commanding The Frigate Le Thetis

and the Corvette L'Esperance,

Lying in Port Jackson

in MDCCCXXV."

Lower down the hill is the grave of Le Receveur, naturalist of the Astrolabe, who died while the ships were in Botany Bay, of wounds received from the natives of one of the Navigators' Islands. "Malice unprovoked and treachery without a motive," as an old print puts it, on the the part of the natives, resulted in the massacre of M. L'Angle, captain of the Astrolabe and twelve others of a party who had gone ashore, and in the wounding of Father Le Receveur who lingered till his ship reached Botany Bay, and then expired. His grave was dug near a tree which for a long time sheltered the little mound of earth, and near which his shipmates elected to his memory a slight monument, with an appropriate inscription. This monument being soon afterwards destroyed by the natives. Governor Phillip had the inscription engraved on copper and affixed to the tree, this kindly attention to the remains of the deceased naturalist being all the more readily per-formed because De La Peyrouse had paid similar respect to the remains of a British naval officer who was buried at St Peter and Paul Kamtschatks. The tree upon which Governor Phillip caused the inscription to be placed has long since disappeared. Tradition says that it fell, and that a block taken from it was exhibited in the London Exhibition of 1851, and afterwards removed to the Louvre in Paris, where it now is. Two young trees have sprung from the stump of the old one, and they bend over a gravestone railed in with an iron railing. Old the stone looks, and brown and weatherworn - like the gravestones that used to crop up from the ground and show portions of quaint and half-defaced inscriptions in the George-street cemetery, where the Town Hall now stands. There is no date on the stone to indicate when it was placed there, but it probably dates as far back as the obelisk. A fanciful iron cross stands at the head, and a cross cut in the stone is at the foot, and between is an inscription running as follows: -

Hie Jacet

Le Receveur

Ex. F.F. Minoribus

Gallian Sacerdos

Physicus incircum navagatione mundi

Duced. De la Perouse

Obiit Die 17 Feb.

Anno 1788.

Quiet and secluded was the spot where the body of the priest was laid; commanding and appropriate was the site chosen for the monument to De la Peyrouse. Sheltered from the effects of storms which have since swept the trees in the locality and denuded them of leaves as though a hurricane had passed over them, there was nothing to disturb the quietness and solitude of the place after the hills had ceased to echo the sounds from the ships in the bay, but those things which a naturalist would love and one can imagine that the peacefulness surrounding the grave would remove much of the impression of its loneliness. The obelisk not only commands an extensive prospect of the Bay, but is immediately opposite the historical spot where Captain Cook first landed, and where also a monumental obelisk has been erected. For many years after the De la Peyrouse monument was placed in its present position it and the grave were with one exception -that exception being a well dug to water the French ships - the only evidences that white men had ever been in the locality; but now there are to be seen several substantially built houses, and a small fishing village. A Custom-house station is there, and the New Zealand cable coming ashore at this spot, there is a telegraph station also. The well dug by the sailors of the Astrolabe and Boussole is not far from the grave, and near the beach. It looks now nothing but a hole excavated at the foot of three or four curiously twisted tea trees but there is fresh water in it, and the water rises and falls with the tide. The religious service of yesterday was performed in a tent erected near the grave, and its object was to seek the aid of the French Government towards erecting a small Roman Catholic chapel on the spot so interesting to the French people. In that desire Father Holahan, one of the Franciscan brethren at Waverley, the order to which Father Le Receveur belonged, invited the captain and officers of the French ship Rhin, and the French Consul, to attend the service, and there were present yesterday: - M. Ballieu (French Consul), Madame Ballieu, Captain Mathieu (commander of the Rhin, and French Commissioner-General to the International Exhibition) M. Guth, M. Cauvin, and M. Verge (officers of the Rhin), M. Chauvin, and M.Bechet M.A. Veron, M. Jaubert, M. Harel, M. Lerede, M. Rey, Mr. Tarleton, Mr. T Butler, Mr. J. G. O'Connor, and others. Mass having been celebrated, Father Holahan delivered a short address to the congregation upon the history and virtues of the priest near whose grave they were assembled, the greatness of the French nation, and his desire to see a church raised on this spot through the munificence of the French Government. The service, which was a short one was entered into with earnestness by those present, and at its close many of the visitors re-paired to the residence of Mr M'Dermott, Custom-house officer, and partook of his hospitality.

Not the least attraction of a visit to the village of La Perouse at the present time is the gorgeous display of spring flowers in the bush. They began to be seen soon after the Sir Joseph Banks Hotel, at Botany, is passed and all the way to the telegraph station are in the greatest profusion, including apparently all colours and all varieties. The roads, too, are in very good condition, either by way of Botany or by way of Randwick. The country along the shore of Botany Bay towards La Perouse, and for some distance back, presents all the aspects which make it desirable that it should be dedicated as a public reserve, and placed under the control of trustees, and the sooner this is done the better. LA PEROUSE. (1879, September 15). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 6. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13453568

Lapérouse took the opportunity to send his journals, some charts and also some letters back to Europe with a British naval ship from the First Fleet—Alexander. He also obtained wood and fresh water and, on 10 March, left for New Caledonia, Santa Cruz, the Solomons, the Louisiades, and the western and southern coasts of Australia.

Lapérouse wrote that he expected to be back in France by June 1789. The documents that he dispatched with Alexander from the in-progress expedition were brought to Paris, where they were published in 1797 under the title Voyage de La Pérouse. However, neither he nor any of his men were seen again.

Rescue mission of d'Entrecasteaux

On 25 September 1791, Rear Admiral Bruni d'Entrecasteaux departed Brest in search of Lapérouse. His expedition followed Lapérouse's proposed path through the islands northwest of Australia while at the same time making scientific and geographic discoveries. The expedition consisted of two ships, La Recherche and L'Espérance.

In May 1793, he arrived at the island of Vanikoro, which is part of the Santa Cruz group of islands (now part of the Solomon Islands). D'Entrecasteaux thought he saw smoke signals from several elevated areas on the island, but was unable to investigate due to the dangerous reefs surrounding the island and had to leave. He died two months later. The botanist Jacques Labillardière, attached to the expedition, eventually returned to France and published his account, Relation du voyage à la recherche de La Pérouse, in 1800.

During the French Revolution, Franco-British relations deteriorated and unfounded rumours spread in France blaming the British for the tragedy which had occurred in the vicinity of the new colony. Before the mystery was solved, the French government had published the records of the voyage as far as Kamchatka: Voyage de La Pérouse autour du monde, 1–4 (Paris, 1797). These volumes are still used for cartographic and scientific information about the Pacific. Three English translations were published in 1798–99.

Extracts from the latest English Papers.

PEROUSE.---After the lapse of years, some glimmering information has reached Europe with respect to the fate of the French navigator, Perouse. He failed on a voyage of discovery with two frigates and, after performing part of his voyage, touched at Botany Bay ; but from the period of his sailing from New South Wales, no account was ever received from him. A vessel was sent from France in search of him, but in vain. At length an American ship, which had traversed the South Sea brought to the Mauritius in Feb. last some information, which gives strength to the conjecture that have been formed of the unfortunate Navigator's having been massacred with all his crew. The following article is extracted from the Moniteur of Sunday last, into which it was copied from a Journal printed in the Isle of France :--

" Captain Ingenold, commander of the American ship Charlotte, arrived from China, says, that he learnt in his voyage to the South-Sea, at the Sandwich Islands, and on the North-west coast, that before the Revolution of France, without being able to determine precisely the year, a vessel from Brest had, in the month of April, anchored in the Bay of Comshervar, a bay which is 54 deg. 13 min. North, opposite Eaglefield-bay, in the island called Queen Charlotte's Island. That this vessel, having a great quantity of sick, was attacked by the Islanders, who got on board the moment the crew were employed in reefing in the sails ; that they massacred the Captain, who was on the deck, and the whole crew, with the exception of a young man whose fate is unknown. It is added, that the Islanders destroyed the vessel after having unloaded it. It is presumed that this vessel was M. La Perouse's or her companion."

Extracts from the latest English Papers. (1803, May 22). The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842), p. 2. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article625590

Count De la Perouse.

We last week mentioned having received some interesting information, which appeared to throw some light on the fate of the unfortunate French Admiral, Count De la PEROUSE, and pledged ourselves to give a detail of the circumstances this week. The following statement we have been favoured with, and, as we can place dependence in the veracity of our Correspondent, we lay it before the Public as we received it :-

"On the 8th of January, 1810, I was sent on shore with several other men, from the ship Sydney Cove, Captain CHARLES M'LARREN, at the South Cape of New Zealand, in order to procure seal skins. After leaving the vessel, I made towards the shore, and was some distance from it, when it began to blow a gale of wind directly offshore. This forced me to go into a Bay near the Cape, contrary to my wish, as I had passed it before, and saw that it was iron bound, having no beach. —I proceeded to the N. W. end of this bay, to pro-cure the best shelter I could, and found, to my great surprise, an inlet. At the end of the inlet, there was a pebbly beach, where we hauled up our boat for the night. The next morning, one of my men told me he had found a mast near the beach ; I went to look at it, and found it to be a ship's top-mast, of a very large size. It was very sound, but to all appearance, had lain in the water a long time. It was full of turpentine, which of course had preserved it. As I was compelled by contrary winds to remain three days in this inlet, I had time narrowly to examine this mast ; I measured it, and found its length to be 64 feet from the heel to the upper part of the cheeks ; the head had been broken off close to the cheeks. There were two lig-numvitæ sheaves near the heel, which I took out. Each of these sheaves were 16 inches in diameter—had an iron pin, two round brass plates a quarter of an inch thick, and four small iron bolts or rivets, which went through the sheaves, and the two brass plates to secure them. I have been some years in the British Navy, and am well assured that this bushing was not English. On taking off the plates from the sheaves, I found inside each of the plates, No. 32, which was, without doubt, the numher of the vessel which the mast be- longed to. Every ship in the British Navy is numbered, and I doubt not it is the case in other countries. When the ship came for me and my men, I informed Captain M'Lar-ren about the mast. He looked at the work, and gave it as his opinion, that the bushing was French ; he observed, that he did not know of any vessel that was ever lost on that coast that required a top-mast of that size, except the Endeavour, which was towed into Dusky Bay, and every thing belonging to her got on shore. I am inclined to be-lieve, that this top-mast belonged to the vessel in which Admiral De la Perouse sailed, which was never heard of since a month after she left Botany Bay, at the time Governor PHILIP was about forming a Settlement at that place. It is well known, that he shaped his course for New Zealand ; and it is very likely he might have been lost on a very dangerous double reef, called the " Traps," which is about 20 miles out to sea, nearly opposite to where I found this mast. The traps were not charted when De la Perouse was on discovery. The Sydney Cove was nearly lost on them one night ; and, I understand, Mr. KELLY, our Harbour Master, had also nearly fallen a vic-tim on them. I had almost forgotten to say, that, at Captain M'Larren's request, I gave him the sheaves and the mast to carry them to Europe ; but, as the ship he sailed in was confiscated at Rio de Janeiro, it is probable they may have been lost. Captain M'Larren, however, is still sailing out of Rio, and it is very likely he has some memorandum, which will corroborate this statement of mine--the greater part of which I have taken from my log." " W. Nicholls."

From the foregoing, it appears more than likely, that the mast discovered was part of the wreck of the La Boussole, in which De la Perouse sailed ; especially, when we consider his being about to proceed to the coast where the mast was found, when the last tidings were heard of him. The question appears now to rest wholly upon the number 32, which, if the number of La Boussole, proves the identity of the mast beyond a doubt—at all events, it leaves room for much conjecture, which can only be confirmed or refuted by proving what vessel, No. 32, be-longs to which has been lost in these seas.Count la Perouse. (1826, December 8). Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser (Hobart, Tas. : 1825 - 1827), p. 3. Retrieved fromhttp://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2449023

Discovery of the expedition

1826 expedition

It was not until 1826 that an Irish sea captain, Peter Dillon, found enough evidence to piece together the events of the tragedy. In Tikopia (one of the islands of Santa Cruz), he bought some swords that he had reason to believe had belonged to Lapérouse or his officers. He made enquiries, and found that they came from nearby Vanikoro, where two big ships had broken up years earlier. Dillon managed to obtain a ship in Bengal, and sailed for the coral atoll of Vanikoro where he found cannonballs, anchors and other evidence of the remains of ships in water between coral reefs.

He brought several of these artifacts back to Europe, as did Dumont d'Urville in 1828. De Lesseps, the only member of the original expedition still alive at the time, identified them as all belonging to L'Astrolabe. From the information Vanikoro inhabitants gave Dillon, a rough reconstruction could be made of the disaster that struck Lapérouse. Dillon's reconstruction was later confirmed by the discovery, and subsequent examination in 1964, of what was believed to be the shipwreck of La Boussole.

Captain Manby, recently arrived at Paris, has brought a report, supported by presumptive evidence, that the spot where La Perouse perished 40 years ago, with his brave crew, is now ascertained. An English whaler discovered a long and low island, surrounded by innumerable breakers, situated between New Caledonia and New Guinea, at nearly an equal distance from each of these islands. The inhabitants came on board the whaler, and one of the chiefs had a cross of St. Louis hanging as an ornament from one of his ears. Others of the natives had swords, on which the word " Paris" was engraved, and some were observed to have medals of Louis XVI. When they were asked how they got these things, one of the chiefs, aged about 50, said that when he was young a large ship was wrecked in a violent gale on a coral reef, and that all on board perished, and that the sea cast some boxes on shore, which contained the cross of St. Louis and other things. During his voyage round the world, Captain Manby had seen several medals of the same kind, which La Perouse had distributed among the natives of California; and as La Perouse, on his departure from Botany Bay, intimated that he intended to steer for the northern part of New Holland, and to explore that great archipelago, there is reason to fear that the dangers already mentioned caused the destruction of that great navigator and his gallant crew. The cross of St. Louis is now on its way to Europe, and will he delivered to Captain Manby.--Paris Paper. BRITISH & OTHER EXTRACTS. (1826, March 22). The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2185498

2005 expedition

In May 2005, the shipwreck examined in 1964 was formally identified as that of La Boussole. The 2005 expedition had embarked aboard Jacques Cartier, a vessel of the French Navy. The ship supported a multi-discipline scientific team assembled to investigate the "Mystery of Lapérouse".[46] The mission was called "Opération Vanikoro – Sur les traces des épaves de Lapérouse 2005".

2008 expedition

A further similar mission was mounted in 2008. The 2008 expedition showed the commitment of France, in conjunction with the New Caledonian Association Salomon, to seek further answers about Lapérouse's mysterious fate. It received the patronage of the President of the French Republic as well as the support and co-operation of the French Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Higher Education and Research, and the Ministry of Culture and Communication.

Preparation for this, the eighth expedition sent to Vanikoro, took 24 months. It brought together more technological resources than previously and involved two ships, 52 crew members and almost 30 scientists and researchers. On 16 September 2008, two French Navy boats set out for Vanikoro from Nouméa (New Caledonia), and arrived on 15 October, thus recreating a section of the final voyage of discovery undertaken more than 200 years earlier by Lapérouse.

Bastille Day 2013 Laperouse Monument, Sydney photo by Lynda Newnam Previously published: on a website I manage www.laperousemuseum.org

References

1. TROVE

2. Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse. (2017, September 1). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jean-Fran%C3%A7ois_de_Galaup,_comte_de_Lap%C3%A9rouse&oldid=798388809