October 13 - 19, 2019: Issue 424

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment

By Angus Gordon and David PalmerSeptember 2019

Introduction

The campaign for preservation of the Warriewood Escarpment bushland, now called Ingleside Chase Reserve, stands as an outstanding example of how the community and local government can work together to achieve a positive environmental outcome and legacy for future generations. The willingness of the private land owners to negotiate a fair outcome also needs to be acknowledged.

This history recounts the events which occurred within the community campaign and how Pittwater Council responded and took the campaign to its successful completion. It is based on recollections and research by two of those intimately involved in different but complementary aspects of the campaign, Angus Gordon then General Manager of Pittwater Council, and David Palmer from the Pittwater community.

The history comprises a series of short chapters each containing recollections by one of the authors. Together they tell a comprehensive story of a remarkable stage in the larger history of Pittwater Council and its community.

(Cover photo: Pittwater Online News)

Background

By Angus Gordon

The Warriewood escarpment, situated on the upper Northern Beaches is part of the rising ground between the coastal plain and the Ingleside plateau. It is the green backdrop to the suburbs of Warriewood and Mona Vale and part of the view from a number of other nearby suburbs along the coast.

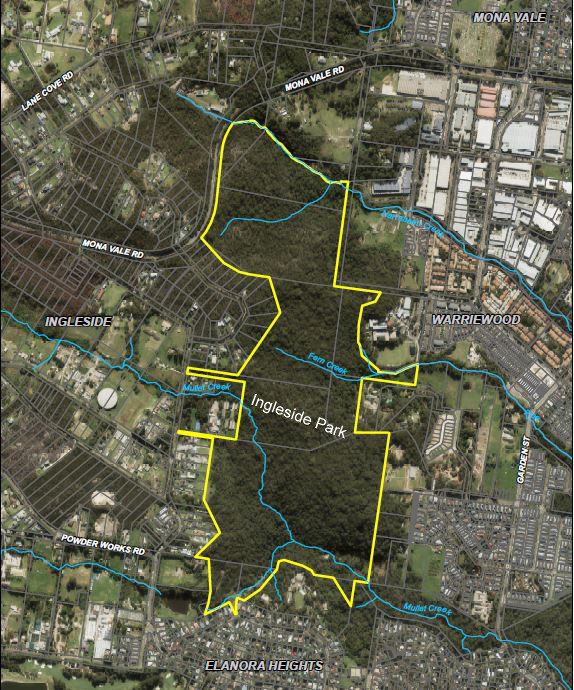

Boundary map of Ingleside Chase reserve 2019. Image: Northern Beaches Council

In the early 1990s the escarpment bushland was made up of a number of privately owned parcels either side of a central 11 ha area known as Ingleside Park. At the time the ownership of Ingleside Park was uncertain, but of the other parcels the two major land owners were Healesville Holdings, who owned about 28 hectares of land to the north of Ingleside Park and the Heydon family who owned a similar sized portion situated to the south of Ingleside Park. Smaller portions were owned by Mater Maria School and the Uniting Church. Regardless of this actual ownership pattern, many in the community were of the belief that the heavily wooded escarpment was public parkland and only a few, including David Palmer, President of the Ingleside Residents Association (IRA), knew that it was not.

In the early 1990s the NSW Department of Planning formally requested the newly formed Pittwater Council to prepare plans for a major land release of the Warriewood Valley/Ingleside area. Studies at the time indicated that the Ingleside region had a number of considerable impediments to overcome before it could be released for residential development. These included the need to significantly upgrade the water supply system, the provision of a sewerage system and the associated connection to, and upgrade of, the Warriewood Treatment Plant and the provision of a fit for purpose road system. There were also major environmental challenges such as management of the bushland including the endangered species of plants and animals, and management of the bushfire threat.

While to a lesser degree Warriewood Valley had similar strictures these were far more manageable. However, unlike Ingleside, Warriewood Valley also had a history of flooding. Interestingly, I, in my previous employment by NSW Public Works as a civil engineer specialising in coastal and flood management, had as part of an investigation into flooding and water quality in Narrabeen Lagoon in the 1970s, developed a preliminary concept for managing water issues in Warriewood Valley by a combination of restored and enlarged creeks with creek line corridors to cope with large rainfall events, along with detention structures and nutrient stripping pondage.

This was further developed in the 1980s, however it then became apparent that the successful management of flooding in Warriewood Valley was dependent on limiting further rainfall runoff from the Warriewood escarpment and South Ingleside areas. Without such limits, and given the relatively flat nature of the Valley floor, any future development in Warriewood Valley would be vulnerable to flooding regardless of any actions taken within the Valley.

In late 1996 discussions took place between Council and Planning as to the future of what was known as the Warriewood-Ingleside land release. Negotiations between myself and the Director General of Planning resulted in an agreed compromise which allowed for the release of 110 ha of land within Warriewood Valley, as a first stage. This excluded the “Buffer Zone” around the Warriewood Sewerage Treatment Plant (STP) and the escarpment region. The “Buffer Zone” around the Warriewood STP had been previously imposed to help risk-manage potential chemical spills at the plant as, at the time, chlorination was the final treatment process before the effluent was released at the cliff base outfall at Turimetta Headland. The 110 ha land release was formally announced in 1997 with Planning agreeing that Council could manage the “Release”.

The 1997 Warriewood Land Release helped focus attention on the concerns first raised by the Ingleside Residents Association (IRA) in 1994 regarding the future of the escarpment. One of the first issues identified was the question of ownership of the area known to a small number of people as Ingleside Park.

Research revealed that the central 11 Ha of the Warriewood escarpment was a dedication made back in the 1920s for the right to subdivide the “Blue Hatched Area” of the Ingleside plateau out from an original 1 square mile land grant to Joseph Kentigen Heydon in 1912 (the original land grant to another person had lapsed and Mr Heydon had informally taken up the grant in the 1890s but it was only formalised in 1912). The 1920s subdivision was prompted by a projected Gordon to Mona Vale railway proposed by the then Government. However, although the 11ha were set aside for “public purposes “at the time of the subdivision Warringah Council failed to take up the dedication, so the land was in limbo.

Iris Hardie, one of my staff who was looking into sorting out the Pittwater property records for me let me know that the dedication had not been finalised. So, we applied to Crown Lands to have the property dedication correctly completed. After several months of argument, and record searching, and an extraordinary effort by Ms Hardie, Crown Lands eventually agreed that Council should be recognised as the rightful owners, in “fee simple”, rather than seeing it as Crown Land, surrendered by default as a result of Warringah failing to complete the dedication.

The Community Campaigns

By David Palmer

The first attempt at development on Warriewood escarpment

I was president of The Ingleside Residents Association (IRA) when I started the campaign against development on the Warriewood Escarpment in 1994. I knew that on both sides of what I understood to be the 11 ha Ingleside Park reserve were parcels of privately owned bushland, which friends and I had walked through many times. I also knew that a few intrepid Ingleside residents used to ride horses from Ingleside to Warriewood through the escarpment land. We considered this land a de facto community asset, so were resolved to protect it when, in November 1994 our association was advised that a 28.7 ha portion of the escarpment which belonged to Healesville Holdings was under threat of development.

Healesville Holdings, a company associated with the Gowings retail family, had lodged an application to subdivide their land into 14 rural residential lots with one residual lot that could be subdivided later[1]. I contacted the Manly Daily and had an article published in which I pointed out the environmental significance of the site and a number of our concerns about the development application[2]. I remember spending hours in the Pittwater Council office at Vuko Place taking notes from the development application and other documents to help with our submissions, as this was in the days before documents were available on the internet.

Members of the Ingleside Residents Association and other concerned locals got busy putting together submissions and lobbying Pittwater councillors and Pittwater MP Jim Longley. The IRA, along with the Warriewood Valley Residents Association (WVRA) and other community groups argued that the best solution to the problem was a land swap of some type.

The WVRA had Henry Wardlaw, a retired senior executive of Department of Urban Affairs and Planning (DUAP), draw up a plan to swap the escarpment lands for some vacant government-owned lots in the “Blue Hatched Area” of Ingleside, an area mostly situated south of Mona Vale Road upon which building restrictions had been placed by Council because of difficulties in servicing the area. We referred to this as the “Wardlaw Plan”[3] and took it to Pittwater Councillors and anybody else who we thought would listen to us.

Phillip Walker, a member of the WVRA, and I decided to take the plan to the executives of Healesville Holdings, which we did at a meeting in their office above the Gowings retail store in George Street Sydney. We were received politely but at the time they showed little interest in the idea of a land swap.

The development proposal was refused by Pittwater Council in early 1995[4] due to environmental impact, lack of satisfactory arrangements for sewage disposal, traffic safety, and inadequate bushfire safety measures. Healesville Holdings appealed to the NSW Land and Environment Court, but the court ruled in 1997 that development approval be refused[5].

In 1996 Angus Gordon, a long term resident of the Pittwater area, was employed as General Manager of Pittwater Council. In the months leading up to his official start date (he was working on the Hong Kong ocean outfalls project at the time and had to complete his engagement before he could be released) he had brought himself up to date with Council matters so by the time he officially started work as General Manager on 1 May, he was familiar with the Healesville development application and understood the concern coming from the community groups.

Meanwhile, the Ingleside and Warriewood residents associations were aware that the Healesville Holdings land was now “in play” and that a revised development application was likely to be put to Council. They continued to campaign vigorously for a land swap, as reported in the Manly Daily[6]. Council was sympathetic, as in March 1997 Councillor Gary Sargent’s motion for a land swap, based on the “Wardlaw Plan” received “in principle” support from councillors[7]. However, as expected, Healesville Holdings once again applied for residential subdivision on the escarpment.

Healesville Holdings’ second attempt at development

In September 1999 Ingleside Residents Association were advised that Healesville Holdings had submitted another development application, this time for 12 residential lots on part of their land[8].

This application referred to the land as “Burrawang Ridge Estate”.

Realising that we needed more community support this time, I decided to approach Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) to form a co-ordinating committee and appeal to the wider Pittwater community. As a member of this organisation, I knew that being a Pittwater-wide environmental group they would add more capacity to the campaign. PNHA formed the Pittwater Escarpment Committee (PEC), a subcommittee of PNHA comprising members of the PNHA committee, representatives of other community organisations and concerned citizens.

At its first meeting on 15 December 1999, held at my house[9], Marita Macrae, president of PNHA was elected chairperson, David James vice-chair, myself secretary and Jeff Skebe treasurer. Other founding committee members were Phil Walker, Karen Nippard, David Mason, Shelagh Atkinson, Robyn Plumb and Jim Revitt, who proved to be a clever and tireless campaigner and an excellent liaison between our group and the Mayor and General Manager. Marita Macrae soon made clear what the Pittwater Escarpment Committee was about:

“The Pittwater community is facing its biggest environmental fight since Pittwater Council was set up almost a decade ago” she declared. “We will not sit back and watch the bulldozers rip.[10]”.

So the committee set to work on a much more ambitious campaign.

Angus Gordon, describes his experience of the campaign by PEC:

“There was strong community reaction [to the Burrawang Ridge development application]. The Pittwater Escarpment Committee was formed and headed up by Marita Macrae, David Palmer and Jim Revitt, three of Pittwater’s leading environmentalists. During the period of consideration of the application there was considerable community pressure for Council to reject the proposal.”[11]

The campaign went into high gear with distribution of leaflets throughout nearby suburbs, information stalls in the local shopping centres, lobbying of Pittwater Councillors, the NSW Department of Planning, John Brogden, our local state member at that time, and collecting signatures on a petition. Jim Revitt took charge of writing the newsletters rallying Pittwater residents to the cause. We formed teams of “walkers” and distributed them throughout the local suburbs.

A significant milestone in February 2000 was a community meeting at Mona Vale RSL Club, a nearby location with a good view of the escarpment. As reported in the Manly Daily, more than 300 people in attendance resolved unanimously that Pittwater Council should reject the Healesville Holdings development application12. The then Pittwater Mayor, Patricia Giles, was present and agreed to support the campaign. She made her support clear in her Mayoral Message column and called on Pittwater residents to “join the fight”.[13] General Manager Angus Gordon got his senior team (Steve Evans, Chris Hunt and Denis Baker) together to consider a way forward. So while the PEC was gathering public support, Council’s senior management team was working on developing an innovative solution.

The Pittwater Escarpment Committee’s public meeting at Pittwater RSL, 2 February 2000. Photo D Palmer

Following the community meeting at Pittwater RSL, Mayor Giles’ support remained solid all through the campaign. At the Council meeting a month after the community meeting she made the bold move of proposing an environmental levy on rates of 5% to assist in the acquisition of escarpment land [14]. This provoked some opposition, but the majority of the community supported it.

The conclusion to Jim Revitt’s address to the Pittwater Council meeting on 15 May underlined the significance of what Council and Pittwater Escarpment Committee were doing:

“This is not just about whether or not we have an environment levy to help save the escarpment. It’s about a partnership between the community, council and government to achieve something that will be admired forever. It is a test of the values and standards of every stakeholder.”[15]

Council certainly showed that they had passed the test as they resolved to meet with Local Government Minister, Harry Woods to discuss ways of securing the escarpment including the levy.

To demonstrate to the Minister the community support for the levy Pittwater Escarpment Committee set about campaigning within the Pittwater community. In addition to leaflet drops and other activities, information stalls in shopping centres along the peninsular were particularly successful in raising awareness of the threat to the escarpment, resulting in many letters to Harry Woods MP supporting the environmental levy and more signatures on the petition. (1863 signatures in total).

Gary Harris supervises letter writing and petition signing at the PEC street stall at Avalon in early 2000. Photo D Palmer

Marita Macrae, Jim Revitt and I accompanied Mayor Giles and General Manager Angus Gordon to the meeting with Minister Woods on 1 June 2000. I knew we had done a good job in getting people to write letters to the Minister when he asked his chief of staff what correspondence he had received on the issue. The reply was that they had received 48 letters supporting a levy and four opposing it.

A couple of weeks after the meeting with Minister Woods Mayor Giles led a mayoral walk through the escarpment, followed by members of PEC and about 150 enthusiastic members of the general community.

“Walking through there makes you realise we have something very special that must be saved” she said [16] To make the occasion even more memorable she read a poem that she had written to mark the occasion, containing this rousing verse:

“People of Pittwater, it’s our duty to heed this vital call,

It’s to be our decision – will the trees stand or fall?

The creeks that flow to the wetlands and on to Narrabeen Lakes

Will surely be affected by the Path that Pittwater takes”[17]

While out in the community PEC was gathering support for preservation of the escarpment lands, Angus Gordon and senior staff of Pittwater Council had come up with a plan to make preservation a reality, and were busy investigating an exchange of Council owned land in Ingleside for the Burrawang Ridge Estate.

Pittwater Council takes up the challenge

By Angus Gordon

The meeting with the Minister for Local Government set the stage for further discussions between the Minister’s office and myself. Although in later years successive NSW Governments became more amenable to environmental and infrastructure levies, at the time (2000) they were not favoured due to a universal political mantra supporting “rate pegging” and limiting Council charges and levies.

Discussions focussed on the environmental significance of the bushland, the desirability of a buffer zone between the existing Warriewood Valley development and any future Ingleside development and, in particular, the need to restrict runoff from the escarpment, that could potentially cause flooding of the Valley region. Runoff needed to be contained to no more than natural levels so as not to endanger the residential development that was well underway in the Warriewood Valley Land Release area. Council’s advocacy was enhanced by the demonstrated broad community support for the levy along with the Planning Department’s increasing recognition of Council’s position that Warriewood Escarpment bushland formed a natural buffer between Warriewood Valley and Ingleside.

All these factors provided me with the necessary arguments to convince the Minister’s office that a specific purpose directed environmental levy was a sensible way forward. The Minister subsequently approved the requested special purpose environmental levy and Council formally established a transparent process for monitoring and auditing the use of funds raised by the levy.

The Land Exchange with Healesville Holdings

Pittwater Council had inherited from Warringah Council a parcel of land, just under 16 ha, that had served as the Ingleside effluent disposal centre. It had been in use for many years for disposing of the sewerage collected by the “pan service” that dominated the Pittwater area before a reticulated sewer service was constructed by the Metropolitan Water and Sewerage Board (Sydney Water) in the 1970s.

The site had also been used by Warringah Council as a Council Depot; an activity continued by Pittwater Council. However it was surplus to needs for Pittwater. Remediation was relatively easy as the old pan service had been discontinued back in the 1970s and the site had benefited, if anything, from the long term composting, having been lying fallow for several decades. So only the areas where the bituminous painting of the pans took place, the depot’s underground fuel tanks and a small area where Warringah had allowed the disposal of restricted substances from a cosmetics factory, had to be dug up and the soil removed to an authorised tip elsewhere. So, once remediation had been completed, and externally audited, the site was an obvious candidate for putting forward to Healesville Holdings as a potential land swap.

The site was classified as community land zoned for recreation but, due to a number of impediments, mainly associated with its remote location, away from public transport, could not readily be used for either Council operations or recreational purposes.

What to do with the Ingleside depot land and how to deal with the Healesville Holdings land, two seemingly unrelated matters, came together one day at my weekly Senior Management Team meeting which, apart from myself involved the three Council Directors, being Steve Evans, Chris Hunt and Denis Baker. We were discussing a number of issues including the finalisation of the remediation with “sign off” from our auditors and the Environmental Protection Agency and then what to do with the property. The next item on the agenda was the strategy to be adopted in the next round of the on-going issue of the Healesville Holdings application, including the likely costs of a further, protracted legal battle in the Land and Environment Court. As we discussed the Healesville application we realised that there might be a possibility of solving both this and the previous matter. The rest of the meeting focused on developing a concept, involving the exchange (swap) of the two land holdings. We recognised this might be a complex process as it involved changes to both the zonings and classifications of the two parcels of land. The idea was put to Council in closed session because of it being commercial-in-confidence at this stage and Council endorsed the recommendation that I, as General Manager, explore the possibility with Healesville Holdings. I arranged a meeting with representatives of the Board of Healesville and they indicated a willingness to consider the matter[18].

Both parties met and agreed to seek to explore a potential “deal” by separately undertaking assessments of the values of the properties and the legal, environmental, and infrastructure construction “risks” involved. To facilitate on-going “without prejudice” meetings to discuss and resolve issues a liaison arrangement was established between a member of the Healesville Holdings Board and myself, as Council GM. I ensured the Council was regularly updated in confidential briefings. At this point in time the meetings had to be confidential because of the nature of the discussions however it was agreed that certain interested community leaders, who understood the importance of being discrete, should be kept in formed, as far as possible, regarding the general direction of the potential “deal”.

The Council’s Ingleside property was a fully cleared site that, at the time, was undergoing remediation to the standard required for residential development. The site had a slight slope to the north that helped provide expansive views of the National park to the north while at the same time making building construction a reasonable easy matter and aiding drainage. Because of its previous use as a council depot the site already had good road access, power and telephone connection so the costs of providing infrastructure were limited to those involved in actual servicing of any individual allotments and could therefore be readily calculated with certainty.

There was however one potentially significant problem. The land zoning for the site, as contained in the Local Environmental Plan (LEP) that applied at the time, required minimum lot size for residential development of 2 ha and, as the site was slightly under 16ha, it potentially meant that the yield would only be 7 lots, not the 8 we had hoped for to make a land swap more attractive. Again Iris Hardie “weighed in” by drawing my attention to a “paper” road reserve along the eastern boundary of the site. This unmade, undeclared road reserve was the property of Crown Lands so I approached Crown Lands to see if they would sell the road reserve to Council so we would be above the 16 ha limit and therefore could achieve an 8 lot subdivision.

Over the ensuing months Crown Lands showed no interest in any proposition even though the “paper” road reserve was technically useless due to developments that had taken place since its creation and therefore a purchase agreement should be a simple process. The only excuse Crown Lands offered was that they were too busy on projects they felt had higher priority. I briefed the Director General of the Department of Local Government on the overall project and requested his intervention with Crown lands. Subsequently he advised me of his frustration in trying to get action on the matter so I approached the Director General of Planning who was already familiar with what Council was trying to achieve in regard to the Escarpment.

As with Council and Local Government the Department of Planning received no satisfaction from trying to get Crown Lands’ cooperation. So, as a somewhat surprising move the Department of Planning volunteered the advice to me that they were prepared to support a 8 lot subdivision of the site on the basis that it was only slightly less than the 16ha required by the LEP and that given the proposed subdivision was to be part of a land swap that secured the northern region of the Escarpment a small variation in the LEP requirements was in the “public interest”. Council was therefore in a good position to provide a reasonably robust assessment of the yield and hence the value of the Ingleside Depot site and the likely costs for subdivision and the provision of services. Through the “without prejudice” liaison meetings this information was “placed on the table” and agreement was reached as to the validity of the information.

Over the months while Council was “sorting out” its side of any deal Healesville holdings were working on the potential yield and costs to develop their area of the Escarpment. Unlike Council, Healesville Holdings found that the potential yield on their land was far more uncertain. Although Healesville Holdings had indicated they were seeking a 12 lot subdivision they, “without prejudice” indicated the actual number would probably only be established through a potentially expensive and uncertain court process that could take a considerable period of time and may result in a lower yield than they were wishing for.

While no agreement on likely lot yield was attempted at the liaison meetings both parties were unofficially of the view it could be 9 or 10. However, before this became an issue, in good faith, Healesville advised that because of the rugged terrain, the heavily wooded slopes and its relative remoteness from services their costs of servicing any proposed subdivision was likely to be substantial. For example it was recognised by both parties that because of the terrain some of the lots would have to be serviced by “aerial” roads; roads built on concrete piles. And then there were the uncertainties in costs and approvals, introduced by environmental issues due to the land clearing for construction of access and services to the lots, and for provision of adequate cleared areas for dwellings given that they needed to satisfy bushfire requirements.

Given the uncertainties regarding legal, environmental and construction costs, along with likely allotment yield and the potential delays these uncertainties represented, and hence the time value of money, Healesville were prepared to consider their parcel of land, although of larger size, most likely had a similar developed value to that of the Ingleside Depot. However they were understandably wishing for certainty that an 8 lot subdivision would be approved and so made their agreement subject to Council formally, and transparently, through the standard public process, achieving approval of the subdivision prior to the “deal” being finalised.

There are two classifications of council held land under the Local Government Act. One is “operational land” and the other is “community land”. Operational land, the classification that applied to the Ingleside Depot at the time, can be sold by council following a relatively simple process. However community land cannot and requires a somewhat complicated, public, and problematic process to be reclassified as operational land before it can be considered for sale.

Understandably Healesville wanted to be certain that if the land swap took place their land would be re-classified as “community land” and rezoned specifically for environmental purposes so that a future Council could not readily simply subdivide the land and “reap the rewards”.

The results of the “without prejudice” meetings with Healesville were formally taken to Council and a resulting in-principle land swap arrangement was agreed between Healesville Holdings and the Council. The cost to Council was the remediation of the site plus the development application cost of achieving an 8 lot subdivision of what was to be formally zoned non-urban. This was funded through an environmental levy. We were of course very careful to ensure the site was fully remediated and carefully, independently, checked before given a “clean bill of health”. It would be for Healesville to meet the actual costs of subdivision.

However, in seeking to undertake this rather “tricky” and complicated transaction (land swap, rezoning and reclassification of both parcels and a one-on-one dealing with Healesville Holdings) and the fact that much of the negotiations had taken place in a commercial-in-confidence environment I was concerned of possible probity issues. As part of my activities when working with the NSW Public Works I had been involved in a number of complicated transactions and had experience in seeking advice from the NSW Independent Commission against Corruption (ICAC) on such matters.

After fully explaining the purpose of the proposal to the ICAC and providing all the confidential paperwork, and Council Minutes of Confidential Meetings to the ICAC they agreed that the “deal” was reasonable and in the public interest and so they supported the proposed actions and the process I had outlined. However they added the rider that that they did so provided we offered the same deal to the Heydon family who still owned the over 30 ha parcel at the southern end of the escarpment.

The land swap deal with Healesville Holdings required a number of matters to be resolved “simultaneously” in order that both parties could be assured that the full agreement would be completed to the satisfaction of both parties. That is, the rezonings and reclassifications, along with the subdivision and exchange of titles had to all occur with certainty, effectively at the same time, an apparent impossibility given the complexities of each of the processes.

Again in my time with Public Works I had been involved in similar dealings and was therefore familiar with a process sometimes referred to as a “Put and Call” contract, a somewhat complex contract to construct. It is an agreed and signed formal contract, which put simply, details all the processes that have to be completed before the contract is finalised and includes an agreement that once the process is formally commenced both parties undertake to fulfil their agreed obligations and that until such time as that happens the “deal” is not finalised, nor can either of the parties pull out part way through without being exposed to penalty.

But we still had a major issue to overcome.

The Heydon Family land

Given we had no further land to swap and certainly didn’t have the funds to purchase the Heydon land I approached John Heydon (who lived in Perth) to see whether we could reach some agreement, or at least if he would, on behalf of his family, raise no objection to the deal with Healesville.

It is remarkable how a common interest can help bring people into a respecting and trusting relationship. Serendipitously John was a keen sailor at the South of Perth Yacht Club. He was also involved with the running of the Club. I had been involved in sailing for many decades, at the Royal Prince Alfred Yacht Club at Newport and was likewise involved in the running of the Club, and so we had a lot in common as a basis for striking up the type of relationship necessary for a cooperative exploration of a way forward.

I flew to Perth (at my own expense, later reimbursed by Council after the deal was secured) to meet face to face with John and his family. They were very pleasant and cooperative but understandably saw the land as part of their children’s legacy and so wanted a fair deal. They were not interested in undertaking development of their land and simply wanted Council to purchase it. At the meeting we explored an in-principle price for the property based on the value both Council and Healesville Holdings had previously agreed was the value of the proposed land swap for the similar sized parcel at the northern end of the escarpment, with similar constraints.

While this was potentially a very favourable outcome, unfortunately I had to advise the Heydons that at the time we didn’t have the funds to consider a deal, even with the environmental levy. However I undertook to explore options further and the Heydons agreed to wait.

I then approached the Director General of the Department of Planning on the basis that the Department operated a grant funding program for the purchase of land for community purposes that was sourced from subdivision levies paid to Planning by councils.

Pittwater, and before it Warringah had contributed to this fund for many years but were as yet to call for a grant from the fund. I pointed out to the Director General the fact that Council had effectively already acquired half the escarpment and therefore requested that Planning provide matching grant funds for land acquisition. That is, Planning provide the necessary funds for the purchase from the Heydons.

The deal was almost across the line except the Department still wanted Council to put up half the purchase price of the Heydon property. I had previously tried to reduce the price by pointing out to the Heydons that there was some land just over the western crest that was in the property boundaries but could be subdivided as it was over the crest of the escarpment. However with the Heydons now living in WA they felt that a subdivision undertaken by themselves was somewhat difficult and perhaps problematic.

So, given this land was within the area to be purchased I again approached the Planning on the basis that this land could represent Council’s half. The Department agreed that if Council would subdivide those blocks out, and rezone them the Department would provide the full purchase price and then sell the subdivided blocks to recover what was notionally the Council’s share. It would then transfer the remaining 30 Ha to Council in “fee simple”. Off to the ICAC again to check they were comfortable with both deals, which they were. And so the deals could proceed to bring the Ingleside escarpment under the ownership of Pittwater Council, in fee simple as Community Land for environmental purposes.

Irrawong Waterfall on Mullet Creek, in what was formerly part of the Heydon Estate. Photo: Dragonfly Environmental - Pittwater Online News

Community Groups continue the campaign

By David Palmer

While Angus Gordon was dealing with the challenge of acquiring the Heydon family land, Pittwater Escarpment Committee gathered community support for the proposed land exchange between the Healesville Holdings land and Council’s Ingleside Depot land. Members of the group sent out newsletters and held stalls in local centres where the need for a land exchange was explained to community members. Signatures on a petition were collected and letters supporting the proposal were encouraged. The group also conducted a survey of local residents which showed overwhelming support. The receipt by Council of 100 letters plus a petition with 153 signatures in favour and only four letters against was reported to Council on 20 November 2000 and assisted their decision to enter into a Heads of Agreement for a land exchange with Healesville Holdings.

As previously stated, for the land exchange to proceed the Council owned land at Ingleside had to be reclassified to operational land and the Healesville Holdings land needed to be rezoned to Environmental Protection.

A public hearing on the reclassification was held in May 2002 where it was recognised that the acquisition of the Healesville Holdings land had overwhelming community support. The hearing approved the land exchange and cleared the way for this parcel of land to be brought into public ownership. On 3 June Pittwater Council formally gave its approval, so the public campaign for preservation of the Healesville Holdings land on the Warriewood Escarpment was over[19].

Pittwater Escarpment Committee’s attention now turned to the other large parcel of privately owned bushland on the escarpment, the land owned by the Heydon Family. Given the ICAC advice to Council, a solution for this parcel land was necessary before the Burrawang Ridge Estate transaction could be finalised.

As recounted above the Heydon Family were prepared to agree to the Healesville Holdings land swap provided that an agreement could be reached on the purchase of their land. A report to the Pittwater Council meeting of 20 November, 2000 outlined the requirement by the Heydon family that: “the heads of agreement [with Healesville Holdings] be amended to include a clause that the agreement with Healesville Holdings is conditional upon a satisfactory outcome being negotiated with Heydon Investments PL in relation to their land holding.”[20]

In 2001 the Department of Urban Affairs and Planning (DUAP) agreed to purchase the 28 ha Heydon Estate. Mayor Giles called it “the biggest thing that has happened in Pittwater" and said that “Mr Gordon had worked his heart out on this matter”[21].

Celebrating the agreement to acquire the Heydon family land at Irrawong Reserve, December 2001

Left to Right: Angus Gordon, Julie Gordon, Libby Palmer, Henry Wardlaw, David James, David Palmer, Ian Giles, Jim Revitt, Patricia Giles, unknown, Marita Macrae, Gary Harris, Lynne Czinner, John Macrae. Photo: D James

However, the process did not go without incident as in order to make the transaction revenue neutral DUAP proposed that along with the blocks of land it owned on Ingleside Road, it would sell a portion of the Heydon Estate bushland land for residential subdivision. But community opposition to selling escarpment bushland housing grew, leading to formation of a new community group.

Calling themselves Save our Escarpment, the group was led by Elanora residents Richard Howe and Dick Clarke. Pittwater Escarpment Committee joined in the campaign that resulted in Pittwater Council calling a public meeting in May 2004. More than 200 people attended the meeting and made clear their opposition to the proposal to rezone and sell part of the Heydon Estate.

Pittwater Council responded by further negotiating with DUAP and finally in 2004 assisting the purchase of the Heydon Estate with funds from its special environmental levy. The overall deal was finalised in 2006. As the Manly Daily reported, it was “Another green victory for Pittwater.”[22] This required Pittwater Escarpment Committee member David James to honour a promise he had made with Angus Gordon: that if the land exchange was successful he would do naked cartwheels down Bolwarra Road. The promise was honoured late one night, witnessed by Phil Walker and Jan Jones.

But the work was not over yet. While the purchase of the Heydon land involved a relatively simple and straightforward contract the purchase of the Healesville Holdings land was about as complicated as it can get. And at the same time there were other parcels of land on the escarpment that needed to be brought into public ownership.

Plaque at Irrawong Waterfall commemorating the incorporation of the Heydon land into Ingleside Chase Reserve on 30 May 2006. Photo: D Palmer.

Other additions

As negotiations were progressing on acquisition of the Healesville Holdings land and the Heydon family land, Angus Gordon, Chris Hunt and other senior staff of Pittwater Council were also working on the addition of some smaller landholdings on the escarpment.

In 2003, after extensive consultation and negotiations a three hectare parcel was purchased from Mater Maria School with the money coming from Council’s environment levy. As part of the purchase agreement Mater Maria School wished to retain access to a small area of bushland behind the school which they had traditionally used as an “outdoor bush chapel”. This was agreed so the purchase took place.

At the same time a more complex agreement was being worked out to obtain land at the Elanora end of the escarpment from the Uniting Church. Early in discussions Angus Gordon became aware that one of the leaders of the Uniting Church’s negotiation team was his Godfather and although he had lost contact with him several decades before he felt that in the interests of strict probity he should remove himself from any further involvement in the matter. Chris Hunt was therefore tasked with what proved to be rather difficult and drawn out negotiations. However Chris successfully delivered the required result so that Council and the Uniting Church finally agreed to a mix of swaps and a $1.7 million purchase of some of the land. This took many years to accomplish and was finally approved by Council in 2010 [23]. As Angus Gordon had retired in May 2005 he was not GM of Pittwater Council when the deal was finalised, however he remained an interested resident of the Pittwater Council area.

So, with the last piece of the jigsaw puzzle in place, a continuous strip of the Warriewood escarpment stretching from Narrabeen Creek, Warriewood to Elanora was preserved.

Including Ingleside Park, the total bushland reserve had grown to over 70 ha and is now recognised as one of the most important habitat areas in the greater Sydney region.[24]

And a little bit more

Even though Pittwater Escarpment Committee has ceased operations, PNHA still keeps looking for any opportunity to add to the escarpment reserve.

This mindset paid off in 2012 when a rezoning application for 120 - 122 Mona Vale Rd Warriewood went before the Sydney East Joint Regional Planning Panel. PNHA campaigned successfully for about a hectare of bushland and riparian zone to be excised from the property and held for addition to the escarpment reserve.

Closing words

By Angus Gordon and David Palmer

Today the bushland on the Ingleside Warriewood escarpment, now known as Ingleside Chase Reserve, provides a valuable natural asset to the Northern Beaches Community. It forms a natural backdrop to many beachside suburbs, provides for walkers, bird watchers and those just wanting respite in a quiet place away from the hustle of suburban life.

Photo: D Palmer

But most importantly for many it is a reserve for plants and animals native to the Northern Beaches, which are under pressure from increased urbanisation.

The success of the initiative to preserve the unique environment of the Warriewood escarpment in public ownership through the creation of Ingleside Chase Reserve is a testament to the combined efforts of the Pittwater community and the Council. It was the result of the cooperation, respect and trust that developed, and was maintained over an extended period, between key members of the community, the Councillors, Council’s senior staff and the NSW Departments of Planning and Local Government. The goodwill, trust and cooperation of the previous private owners, in particular the Heydon family, Healesville Holdings, Marta Maria School and the Uniting Church were instrumental in achieving the result.

David Palmer:

“It was an honour to work with the many dedicated volunteers from the Pittwater Community who gave their time to campaigning over many years for the preservation of this important natural asset.

Since that time Pittwater Natural Heritage Association has kept the volunteer connection with Ingleside Chase Reserve alive through activities such as surveys of birds and other fauna and work on bush regeneration projects. The association has also successfully campaigned for improved connectivity to Garigal and Ku-ring-gai Chase National Parks to enable the escarpment bushland to continue as a viable fauna and flora habitat.

Through these activities PNHA has developed a close association with Ingleside Chase Reserve which I hope will continue for a long time into the future.”

Angus Gordon:

“In short, apart from the fantastic efforts of community representatives including, but not limited to David Palmer, Marita Macrae and Jim Rivett, and the Councillors and staff we actually owe the Heydon family, and Healesville Holdings a debt of gratitude as, although both needed to get a reasonable return for both families and shareholders, their cooperation, trust, and good will, and patience were fundamental to the success of securing the escarpment. Both were very reasonable and respectful and were pleased to assist in achieving the outcome. We also owe a very specific debt of thanks to Sue Holliday, the then Director General of Planning who from the very first time she was appraised of what we were trying to achieve shared the vision and went “above and beyond” what might be considered her “call of duty” in order to assist in achieving the outcome.”

About The Authors

Angus Gordon OAM was General Manager of Pittwater Council from 1996 to 2005 and was appointed in 2018 as a Director of the Pittwater Environmental Foundation.

David Palmer was president of Ingleside Residents Association, secretary of Pittwater Escarpment Committee and is the current secretary of Pittwater Natural Heritage Association.

Left to right: Angus Gordon OAM and David Palmer

References

- Letter to Ingleside Residents Association from Pittwater Council, 10 November 1994

- Manly Daily 16 December 1994

- The “Wardlaw Plan” was drawn up in 1994 and put to Pittwater Council in a motion submitted by Cr Garry Sargent at the meeting on 3 March 1997

- Letter to Ingleside Residents Association from Pittwater Council, 22 March 1995

- Judgement of Land and Environment Court (number 40119 of 1997) dated 26 May 1997

- Manly Daily: 6 December 1996, 15 February 1997, 11 March 1997 and 19 April 1997

- Report to Pittwater Council 3 March 1997

- Letter from Pittwater Council to Ingleside Residents Association dated 9 September 1999

- Minutes of first meeting of Pittwater Escarpment, December 1999

- Manly Daily, 8 December 1999

- Curby, Pauline, Pittwater Rising, Pittwater Council 2002, p 102

- Manly Daily 4 February 2000

- Manly Daily 27 April 2000

- Report to Council meeting outlining the Environmental Levy proposal in 2000

- Address to Pittwater Council by Jim Revitt, 15 May 2000

- Manly Daily 20 June 2000.

- Save the Escarpment, Poem by Patricia Giles (unpublished)

- Curby, Pauline, Pittwater Rising, Pittwater Council 2002, p 103

- Report to Pittwater Council 3 June 2002

- Report to Pittwater Council, 20 Nov 2000

- Manly Daily 29 November 2001.

- Manly Daily 6 June 2006.

- Manly Daily 14 April 2010

- Ingleside Chase Plan of Management, 2010