April 9 - 22, 2017: Issue 308

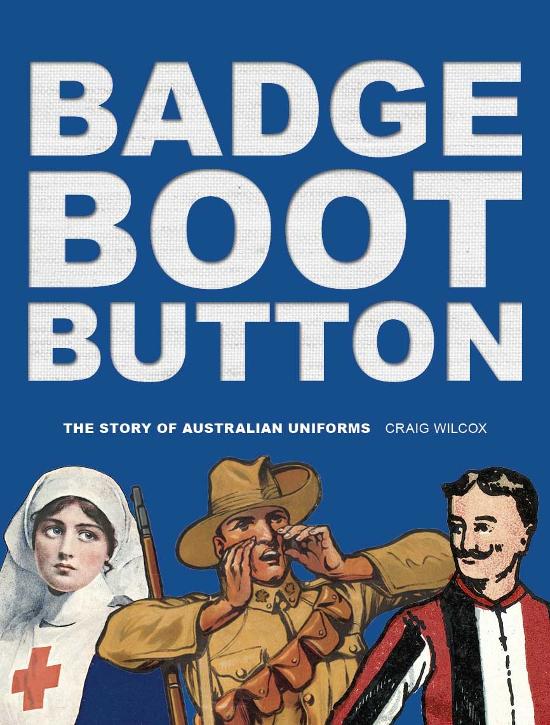

Badge, Boot, Button: The Story of Australian Uniforms by Craig Wilcox

Former Narrabeen resident and Military Historian Craig Wilcox, whose parents still live at Mona Vale and whom he visits regularly, has released a new work through the National Library of Australia, Badge, Boot, Button: The Story of Australian Uniforms.

' Uniforms conceal, and uniforms reveal ... They envelop us in costumes akin to flags, in the bold designs and memorable colours of official, corporate and communal hierarchies ... And like any language, they reveal origins, status, aspirations and insecurities.' Craig writes in the Introduction to this new work.

Many may think of the Services when they think of uniforms but nurses, airline stewards and even football players wear uniforms as well.

Badge, Boot, Button also follows the evolving to an Australian climate our uniforms have had to undergo - those thick woollen uniforms needed by British soldiers in 1788 may be well suited to Northern Winters but those wearing them here may be in dire straits during a mid-Summer heatwave.

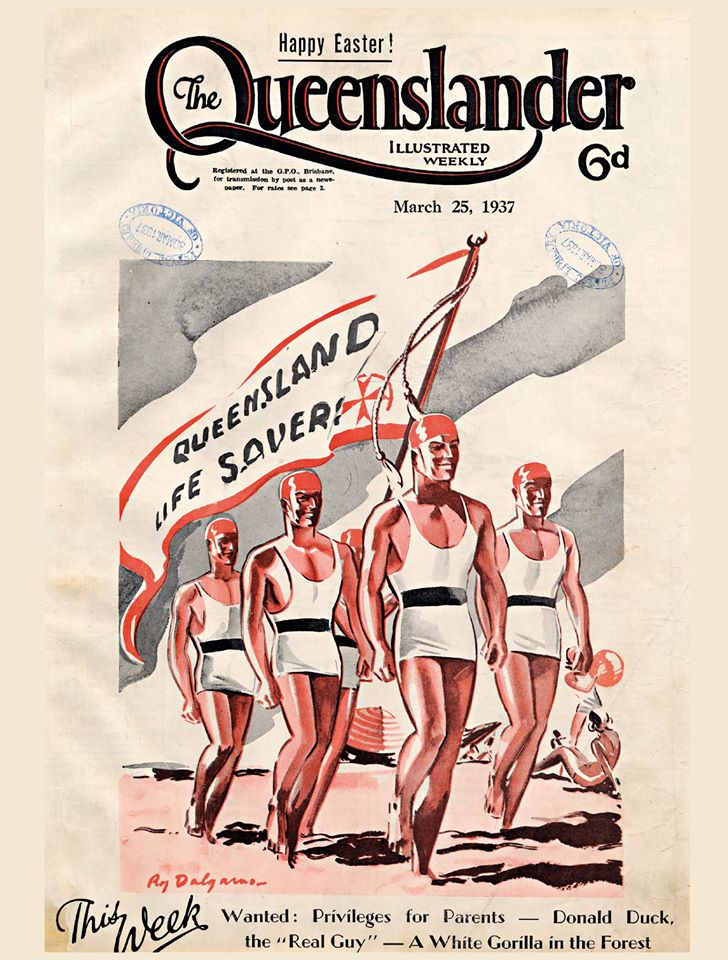

Sports uniforms have changed too, not just to become more stylish, but to help the sportswoman or man excel at their chosen sport - one clear standout here would be the swimmer's costume which has gone from something that may promote drowning to something that will aid an athlete reach their maximum potential. Another is that of surf lifesavers...

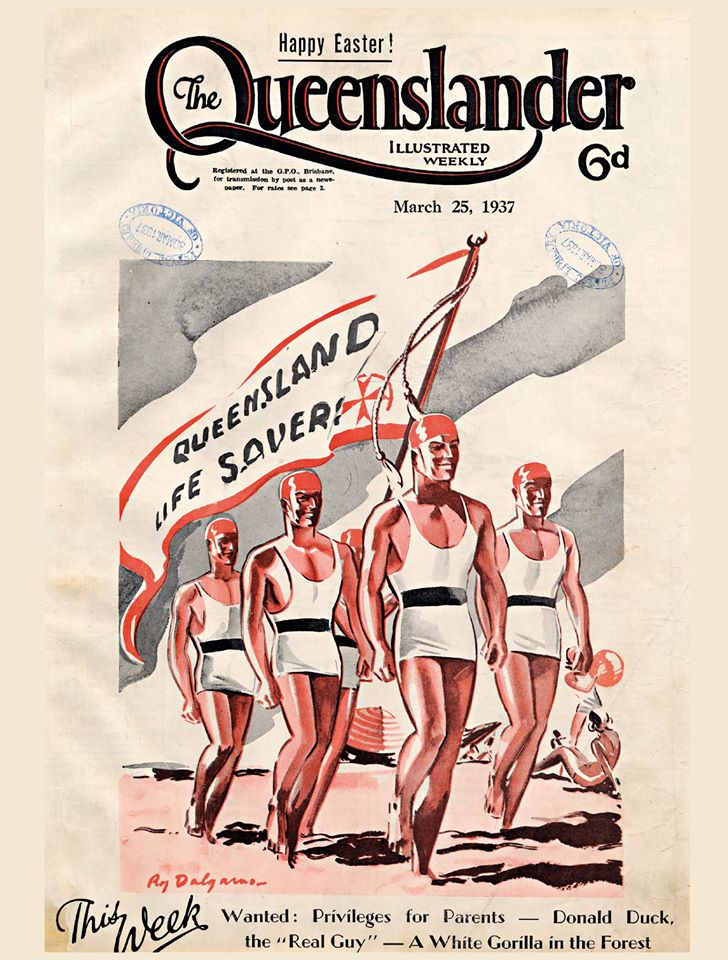

Cover of The Queenslander, 25 March 1937, State Library of Queensland - Page 72; ' Queensland surf lifesavers in the red and white. By 1937, when this illustration was published, a red and yellow cap was becoming official wear for lifesavers on duty across Australia'.

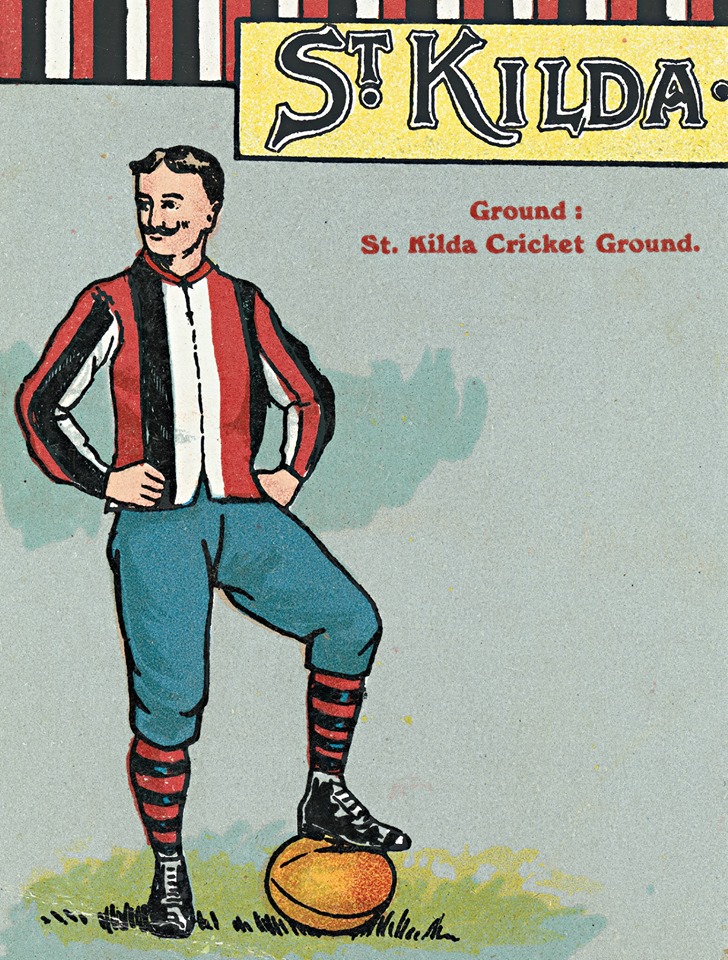

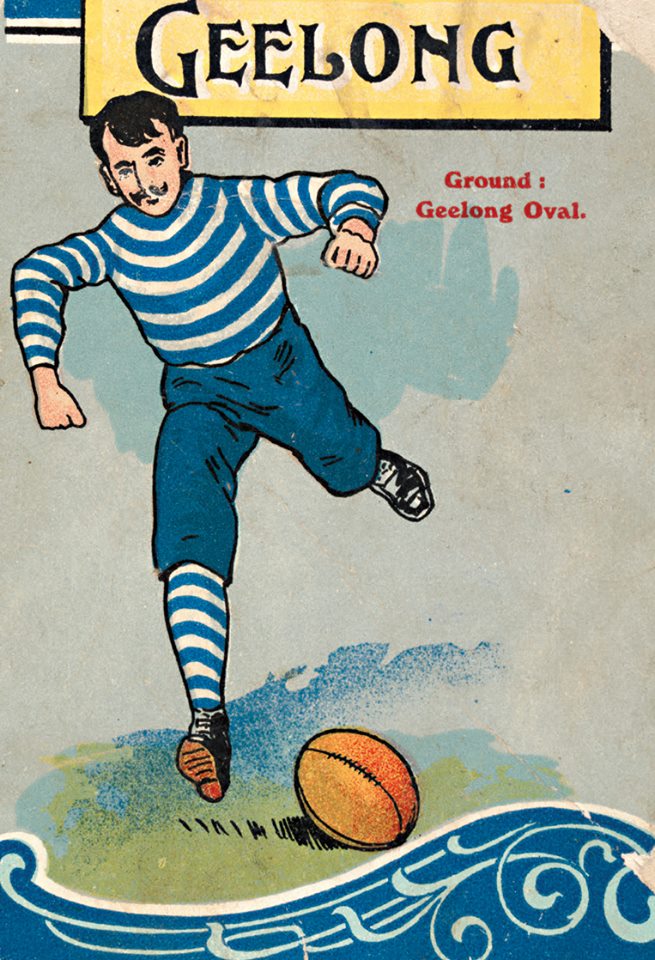

Another would be the many changes we've seen in football which have gone from long sleeved thick jerseys to sleeveless thin versions for even the middle of an Australian Winter.

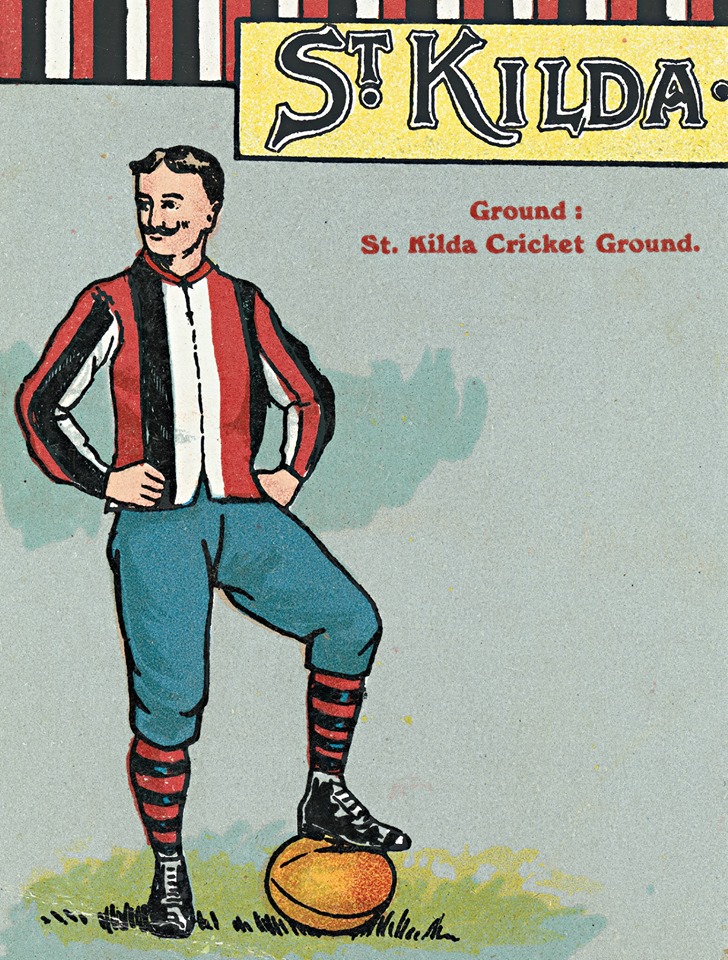

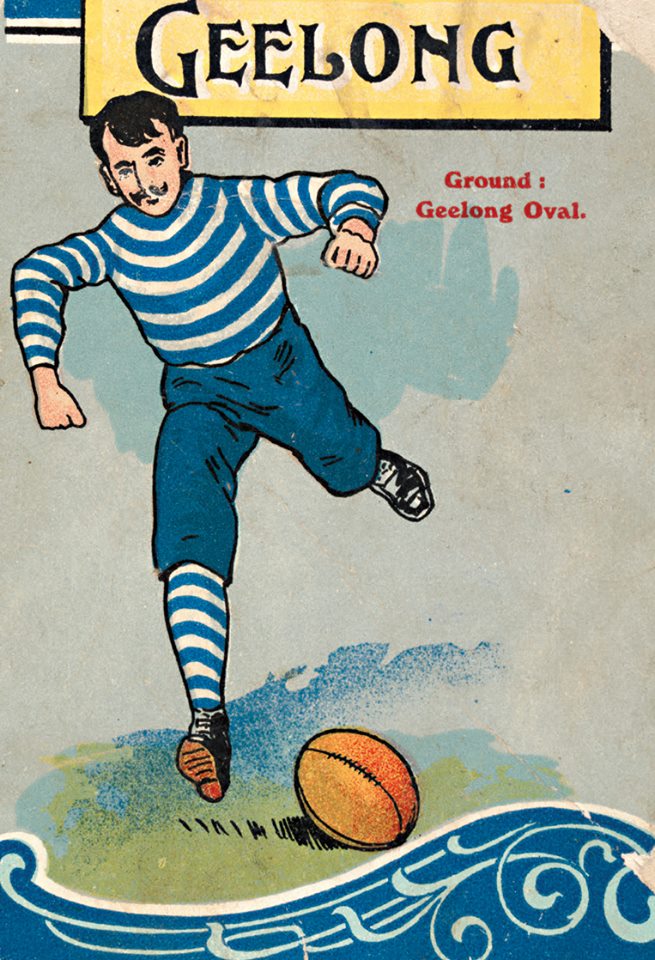

St Kilda (Dundee Scotland: Valentine & Sons, c. 1907) - Pages 44- 45; ' Uniforms of two Victorian Football League teams early in the twentieth century. Still worn today, these apparently timeless colour combinations altered during the First Wordl War. St Kilda swapped white for yellow in 1915 so its coilours mimicked those of allied Belgium instead of imperial Germany. A wartime shortage of blue wool obliged Geelong to wear red stockings in 1918.'

Geelong, c. 1906, State Library of Victoria

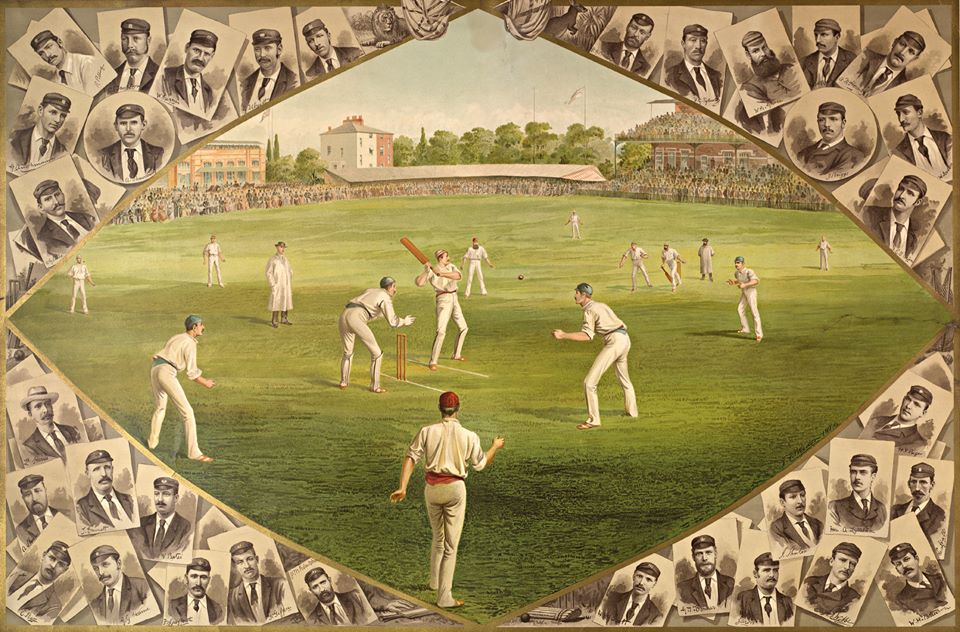

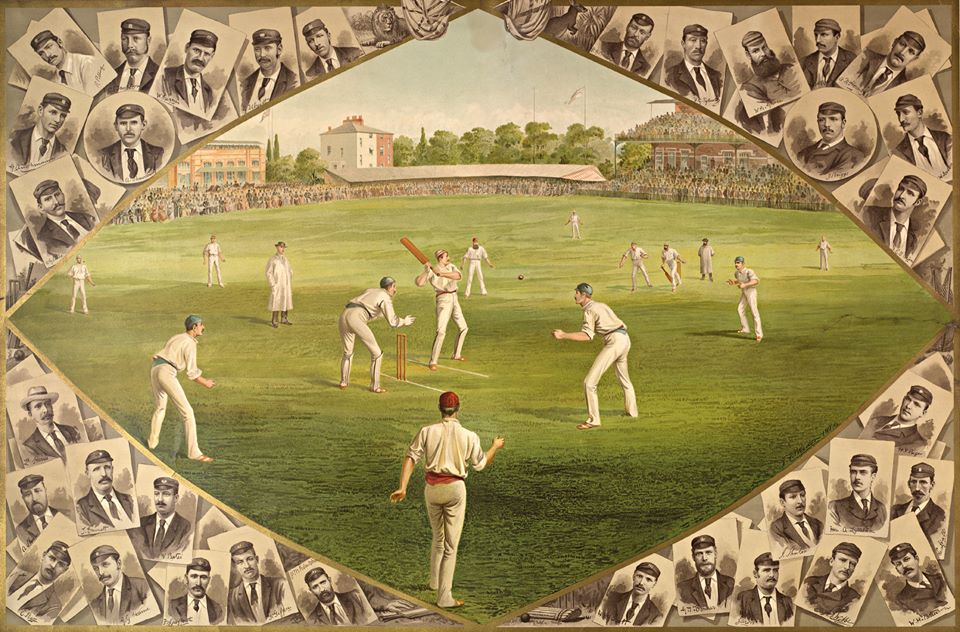

I. F. Weedon, English & Australian Cricketers Great Match, England v. Australia Played at Lord’s Cricket Ground, London, 19th, 20th, 21st July 1886 (London: John Harrop, 1887) Pages 50-51 - 'Australian crickters at Lord's in 1886. Their clothes on and off the field are in the red, blue and white of the Melbourne Cricket Club, which organised their tour; and the caps carry the club's monogram.

The raising of hemlines or changing of materials to suit both fashion or practicality is examined too; army nurses, working behind the scenes of battle, endured a great deal. Their uniforms were described by one unfortunate wearer as being close to literal 'torture', with traditional nurses' caps making it feel as if their heads were 'practically in a vice'.

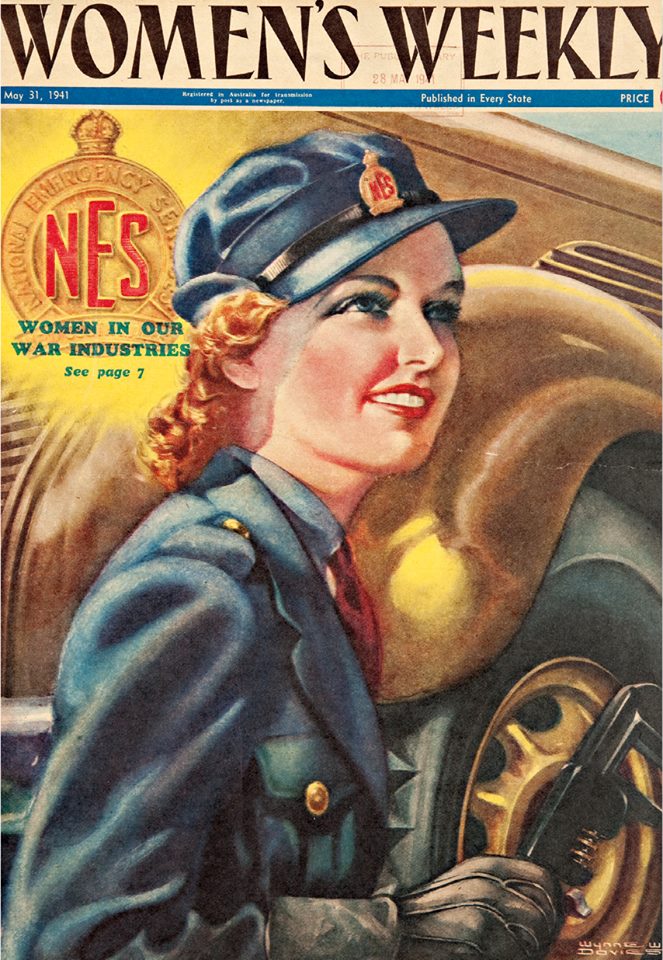

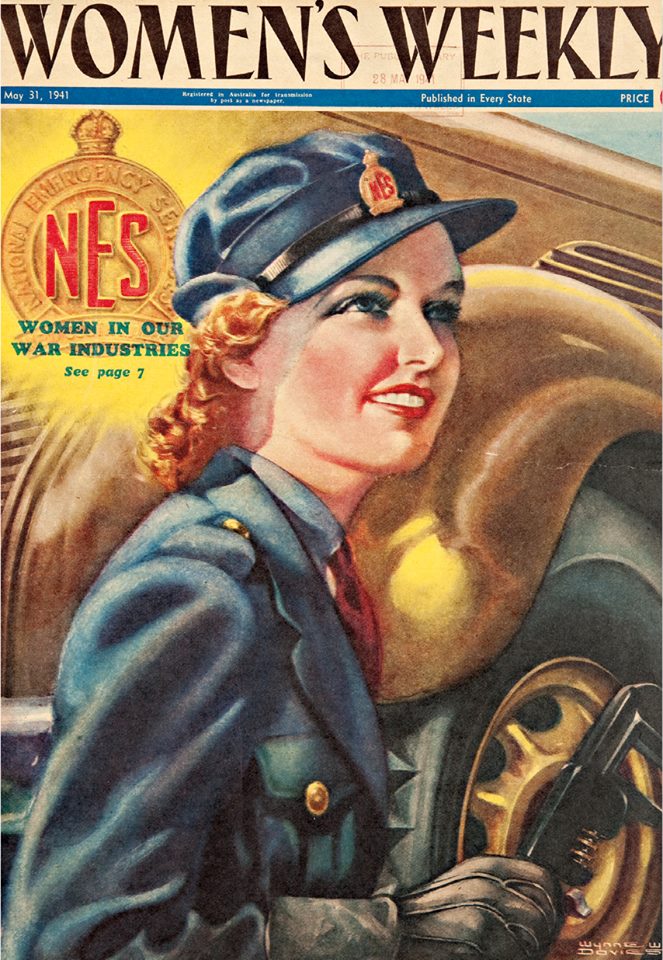

Cover of The Australian Women’s Weekly, 31 May 1941 - Page 91- 'The crisp tunic, peaked cap, leather gloves and maroon necktie of the National Emergency Service, a women's wartime Volunteer unit of motor drivers.

Using newspaper entries and many images, this book provides a unique perspective on changing times in Australia.

Craig examined a Diplomat’s heraldic uniform while researching his new book and we share the article he wrote just so you have some insight into all that has been complied in this wonderful historical work and how a Historian often gets ‘hands on’ when delving into the various aspects of a subject they address.

A Uniform for a Dapper Diplomat

By Craig Wilcox

published April 3rd, 2017 by the National Library of Australia blogs page

During my research for Badge, Boot, Button: The Story of Australian Uniforms, I looked at one of the many curious treasures in the National Library's collection: a large metal trunk painted red and black, with a label engraved ‘P. Shaw Esq'. Inside the trunk, folds of black wool and a burst of feathers resolve themselves into a uniform decorated with gold braid and topped with a plumed bicorn hat. A black leather tube, hard to see at first, contains a sword, exquisite and expensive.

Here I am unpacking Shaw's trunk

The trunk and its contents came to the library in 1976. They were among the relics of one of Australia's first diplomats, Sir Patrick Shaw, who had died the year before. But Australian diplomats don't wear uniform. How, then, do we explain the gold braid, the ostrich feathers, the elegant sword?

European courts were visual spectacles in the nineteenth century, crammed with soldiers in gala dress and footmen in wigs and livery. Politicians at court buttoned themselves into uniform too, generally a blue coat heavily and expensively ornamented with gold. Diplomats who were not soldiers wore similar dress.

Detail of Sir Patrick Shaw's diplomatic uniform, c. 1940, nla.cat-vn882877

The British version of court dress was sometimes called the Windsor uniform, sometimes diplomatic dress. It was rarely worn by politicians. Only two of seven federal government ministers sworn in on 1 January 1901 wore it, and it was rarely seen again. Prime Minister Edmund Barton set a precedent that day, dressing in the stately black emblematic of the middle class men who then dominated English-speaking societies.

Yet there was a world elsewhere, more formal, more martial, more hierarchical, and the new Australian nation would eventually have to trade and engage with it. British diplomats wore Windsor uniform on formal occasions. Would their Australian counterparts wear it when the first overseas posts were established in the 1940s? The government decided that formal civilian clothing would be sufficient, ‘although, technically,' one newspaper argued, ‘Australia might be entitled to adopt the British uniform'. And tempted, too. Why should British diplomats look more important than Australian ones?

We may never know whether it was personal taste or professional calculation that prompted young Patrick Shaw to have a Savile Row tailor make up a Windsor uniform for him on his posting to Tokyo in 1940. Or how much it cost. The coat and trousers bore a prudent amount of gold decoration, enough to advertise the prosperity and status of a middling nation without showing off. If a truly formal occasion required them, a pair of breeches could be substituted for the trousers. The feathered bicorn, flat and without features on one side, would slip neatly under a right arm as the hand rested, following tradition, on the pommel of the ornamental sword.

Sir Patrick Shaw's diplomatic uniform, c. 1940, nla.cat-vn882877

Shaw was interned when Japan went to war with Australia late in 1941, but was mercifully released a year later. He remained a diplomat but almost never wore his uniform again. Heraldic clothes seemed a little obsolete after 1945, at least in English-speaking countries. A design for a distinctively Australian diplomatic outfit was proposed by staff in the Manila embassy in the 1960s, but it was overruled by the ambassador, Francis Stuart, who himself wore Windsor uniform on occasion. ‘I took advantage of the late King George VI's dictum that all diplomatic officers carrying the Crown commission would wear the same rig,' Stuart explained. ‘I certainly found it better to wear King George VI's uniform in Bangkok, Phnom Penh, Manila and Kabul, than a morning coat or tails, which I should otherwise have had to endure.'

Appointed Australia's ambassador to India and Nepal in 1970, Patrick Shaw did as Stuart had done on one occasion. He brought his old uniform with him, and wore it when presenting his credentials to Nepal's King Mahendra. Shaw's entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography describes him as punctilious about etiquette and a ‘dapper dresser who retained into middle age a boyish look'. That physique enabled him to squeeze into a coat made for a young man 30 years earlier. ‘I can remember him putting it on for festive occasions and he was proud of the fact that it fitted for his presentation of credentials to King Mahendra many years later,' his daughter Karina Campbell later recalled.

Perhaps it was the last time an Australian diplomat wore Windsor uniform. Civilian dress was now entrenched for ambassadors, and when Alan Renouf, head of Foreign Affairs, later in the 1970s proposed a uniform the idea was swiftly vetoed. Shaw's uniform can rest in its metal case.

Badge, Boot, Button: The Story of Australian Uniforms

Publisher: National Library of Australia

Edition: 1st Edition

Pages: 172

Publication Date: 01 April 2017

Bind Format: Paperback

$44.99 - available to purchase online here

At first, the Australian military followed Britain's example in regards to uniforms, fitting soldiers out in the traditional 'red coats'. These were impractical in the scorching heat of the new environment, and were widely mocked - unsurprisingly, given the gold lace, elaborate plumes and decorations that accompanied them. 'Badge, Boot, Button' explores the army's gradual adaptation to the environment, complete with images of original uniforms. It follows the struggle of a new country attempting to remain true to British roots while creating something new.

While soldiers had their own struggle with uniforms, army nurses, working behind the scenes of battle, endured a great deal more. Their uniforms were described by one unfortunate wearer as being close to literal 'torture', with traditional nurses' caps making it feel as if their heads were 'practically in a vice'.

Uniforms also played a role in the lives of Australian civilians. The nation was scandalised as swimsuits worn by athletes and lifesavers gradually became shorter; one athlete shortened her own full-length track uniform with scissors after realising her non-Australian opponents, in shorts, were far better adapted to track events. There was greater shock when women's hemlines lifted and this was reflected in uniforms, from that worn by air hostesses to the clothes of tram conductors.

The images in the book create a window into the past, providing the reader with images of the impractical yet dashing officer's uniforms of colonial times and of the 'magpie' suits worn by the worst-offending convicts. This is supplemented with colourful, more recent images, showing uniforms created by professional designers, such as the distinctive designs used by QANTAS in the 1970s.

Using newspaper entries and many images, this book provides a unique perspective on changing times in Australia.

Craig Wilcox

Associate, Centre for Historical Research, National Museum of Australia

Craig Wilcox is a historian who lives and writes in Sydney, Australia's oldest city. He's worked at the Australian War Memorial, has held a fellowship at the Menzies Centre for Australian Studies in London, and is an honorary Associate of the Centre for Historical Research at the National Museum of Australia. His current projects included this history of wearing uniform in Australia, and a psychogeography of Sydney's Hunter Street.

Pittwater Online previously ran an insight on Craig's 2014 release A Kind Of Victory: Captain Charles Cox And His Australian Cavalrymen.