September 13 - 19, 2015: Issue 231

The John Street Heroes

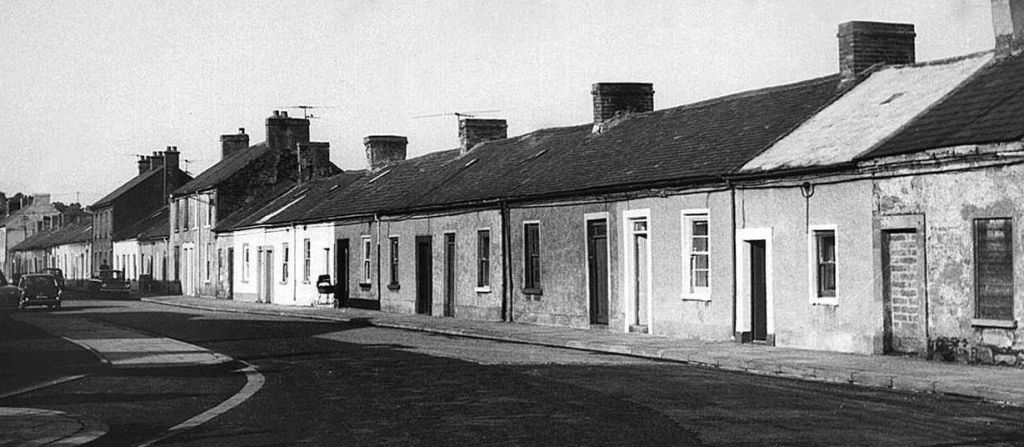

John Street - Newtownards

The John Street Heroes

By Warwick Dalzell

By Warwick Dalzell

Life in Northern Ireland during the Second World War was, paradoxically, more prosperous for most people than it had been in peacetime. Unemployment had been reduced drastically after the privations of the Great Depression, in many areas to its lowest level on record. There was less evidence of poverty and people generally seemed happier, better fed and fewer children shuffled around dressed like paupers.

The underlying social and political divisions still surfaced about the Twelfth of July but otherwise relations between the two communities (Catholic and Protestant) in Northern Ireland were peaceful enough. Newtownards where I was born was a small, largely Protestant town and it is probably because of the demographics, that the majority community was more tolerant of the Catholics who lived there, than was the case in many of the hard line interfaces in the city of Belfast.

Nevertheless the Twelfth of July was still celebrated with style, some would have said with panache if they had known the word, and at that time of the year children were just as likely to imitate their elders, particularly those who were more ostentatious in their celebrations. Children can of course be cruel and some members of the Catholic community suffered at their hands on those occasions when the rules were bent.

Newtownards was part of the Scottish settlement of the early 17th century and the dialect of those early settlers still survived in the area during the forties and fifties of the 20th century.

Consequently many casual visitors to the town needed the services of an interpreter; although we were unaware our version of the King's English was a far cry from the polished tones of the BBC.

There were lots of young families in the street and as time went by the number of children increased rapidly. The majority was Protestant with the odd Catholic family, so we grew up with little experience of the Other Tradition, as it is now so quaintly named. As a rule, the larger the family the poorer the people so imagine my surprise many years later to learn Protestants had been the privileged people of Northern Ireland.

There were children who ran about John Street, winter and summer, with the barest of rags to cover their nakedness, and to whom shoes were a luxury beyond their experience. Interestingly, despite the hardships, none of them grew up to be criminals or drug addicts (unless you insist on calling alcohol a drug), nor did they carry into adult life a perpetual chip on their shoulder. Maybe the structure of the society helped. ( an old aunt once said to me, "you have to know your place," and the lesson seemed to be reinforced by the teachings of the different churches).

In this age of affordable international travel it is hard to recall how insular people were in the 1940s. Today a journey across the Atlantic is less fraught than was the move a few miles into another county. Travel from one part of the town to another was more than some citizens managed in a lifetime and it was the rule, rather than the exception, families lived in close proximity to one another. The men of the family might move but mothers and daughters were more like friends and they shopped together, visited each other every day and in the end often shared the same house.

The Model School was a fee paying school, although the fees must have only applied to those deemed 'wealthy' enough to afford them. There were certainly many children from families whose parents were on the dole or who managed to get by on paltry wages, wages which incidentally were often drunk by an errant husband on a Friday night. Childhood ailments were rife. Diphtheria, whooping cough, mumps, measles, chicken pox and even TB were familiar to everyone. One year, 1947? the dreaded infantile paralysis (polio), struck down large numbers of children and of course it was in the days before the Salk vaccine. Smallpox had been almost wiped out thanks to vaccination and I still have my scar to prove it.

Social graces were only gradually learnt under the 'benevolent' despotism of the teacher. Things like handkerchiefs were unknown in many households and many's the poor child was taunted with the mocking 'green sleeves' ( not a reference to the Elizabethan song of the same name). Cold weather in winter was the worst time, when noses ran and les miserables would be seen surreptitiously wiping them with the sleeve of a pullover or in some instances licking the exudations and swallowing hard.

No-one believed those hapless few were lesser people because of their unfortunate habits, at least not among the general school populace. Some teachers would make an example of a child's 'coarse' behaviour but even they were in the minority. The children at the Model School who looked down on the 'poor and afflicted' were regarded as 'stuck up little snobs' by the rest of us and they tended to play with others of a similar disposition. Mind you the 'poor people' were as likely to cast aspersions at those marginally above them on the social ladder or at those considered 'intellectuals', the 'specky four eyes', 'think you're smart', 'swot' (straight out of Billy Bunter) refrains were heard often enough in the playground.

The Model School - Newtownards - opened 1862

I imagined attendance at school was merely an apprenticeship, something I had to 'thole', as part of growing up. There were so many other exciting things to do when the eagerly anticipated bell rang at the end of the school day. But first it was straight out the school gate and as fast as possible back to the sanctuary of John Street. All great enterprises originated in John Street.We children spent most of our waking hours at school or on the street, with the occasional break for food, and often only at the insistence of an exasperated parent. Life was a continuous round of activity, and I don't remember spending much time moaning about being bored and having nothing to do. I'm sure we all complained but there was a natural order to things, which kept us occupied. Just as Nature had her seasons, so we had ours; the conker season, marbles, apples, birling hoops, raiding orchards, collecting hazelnuts from the Planting, the Twelfth, the Fair Day, Halloween and of course Easter and Christmas. There was a time for fireworks (basically when they were available) but it was limited by financial constraints.

Occasionally boys and girls would get together for some games. The Farmer Wants a Wife was one such game. Everybody joined hands in a circle with a 'farmer' in the centre. We would go around and sing or chant

The farmer wants a wife; the farmer wants a wife,

Heigh ho, me deario, the farmer wants a wife

and the 'farmer' picked out a girl and she joined him in the circle. The game went on with

The wife wants a child; the wife wants a child,

Heigh ho, me deario, the wife wants a child

This was followed by a nurse, a dog and a bone. At the end the bone was left alone and all the children ran away, which was better than the alternative when we'd all pat the bone and things could get a bit boisterous.

Most boys played football. If you didn't play football you were liable to be called a 'sissy' and your life was made as miserable as possible. Basil Waugh, who lived with his mother in a small house opposite the Kelly's, fell into that category. He was called a mammy's boy because he didn't come out to play with the rest of us but we knew little about him.

I have digressed. Football was the most popular boys' sport in John Street. Most games started off in an impromptu fashion and coats were often used as goalposts. The ball ranged in size from a tennis ball to a 'bladder', a bladder being purportedly the entrails of a pig Sometimes the 'ball' was simply a piece of cloth with some filling but gradually people who used such 'balls' were referred to disparagingly as 'Hanky ball' players. Anyone who owned a real football was up with the angels but the trouble was if the owner felt he wasn't getting enough of the action he could pick up his ball and leave.

The games got quite robust at times and with occasional bouts of fisticuffs where the claret would be tapped and flow freely, but mostly they were played in a sporting fashion. We had been brought up in the tradition of fair play via the Rover and the Wizard and our heroes like Limpalong Leslie, the crippled footballer, and the Wolf of Kabul and his friend Chung, who helped him, police the Khyber Pass. Chung probably inspired our later interest in cricket for his favourite weapon was Clicky-ba, a brass bound cricket bat. "Lord, Clicky-ba turned in my hand" he would cry as his bat cracked another native skull.

Broken windows and irate householders were an occupational hazard. Occasionally a passing policeman would caution us about the perils of street football, (the main one being the potential fine and the humiliation of appearing in court) but that was a rare event. Maybe John Street was one of the first no-go areas but it was certainly crime free. A broken window and its repercussions were the extent of criminality. When a passing motorist honked his horn while we were playing he received a stream of abuse and usually wasn't game to stop.

Some bright spark eventually came up with the brilliant idea of starting a youth football competition in Newtownards. There was of course a team from John Street, Hillview Star, named after the row of big terrace houses.

You can't imagine the variety of street games. If you weren't playing football what about Hopscotch, although it was more in the domain of girls. A big favourite was Churchie One Over. It required some strength and endurance. It began with a few boys bending down, the leading boy had his head against the wall and the boy behind held on to him and so on. The other boys would attempt to leap as far forward as they could towards the wall and sit on a boy's back. This was repeated until there was no more room. It was a very physical exercise because the boys bending over had to support the weight of one or two boys on their back until the game was over. Fortunately there weren't many overweight boys in John Street in those days.

Thunder and Lightning wasn't for the faint hearted. The aim of this game was to knock someone's door like thunder and run like lightning normally inflicted on people who were disliked and more a winter game, when the darkness gave the player some anonymity.

Occasionally the householder would open the door unexpectedly and the more quick witted would mumble something like, "Please tell us the time" or some such nonsense. This didn't fool anyone but what could they do. Mind you some people were not averse to taking the law into their own hands so it was always a good idea to avoid the house for a while.

We even had a real life gambling game, Pitch and Toss. The proper game was played with pennies so it was normally played by older boys. The pennies were pitched up against the wall of a house. The boy whose coin landed closest to the wall picked up the other coins two at a time and spun them in the air. He tried to catch them on the side of his hand and if they came up heads he got to keep them. I'm positive it's a second cousin to the Aussie game, Two Up. In another version of the game the coins are spun and the player can keep all the coins showing heads. There were no pennies to gamble with so we used bottle tops as a substitute.

The gas lamps in the street provided the base for another game. All you needed was a rope which was knotted to provide a seat.Tie it to the top of the lamp and a child could sit there and swing round and round all day. It seemed a pointless activity and I was never attracted to it but like bowling a hoop with a 'cleek' it had its practitioners.

There were other games like, Kick the Can, Queenie, Queenie, I've got the ball, Turnovers, Guiders and Cock a Roozie. The latter was often played in the yard of the Model School, with a cast of hundreds. Some poor soul had to start off in the middle of the playground. The others would run from one side of the playground to the other. The middle one had to hold tight to one of the passing throng, preferably of the opposite sex .That person would then help catch more people. As the game went on it became easier for the catchers. It could be a very boisterous game and there were accidents. In the end that game was banned from the school yard.

As I said boys and girls tended to play separately but at party time we all got together. Pass the Parcel, Round Goes the Bun, Postman's Knock and Dooking for Apples were party favourites. Round Goes the Bun was played at most parties. It gave us a chance to kiss the girls and not make them cry. We all sang a little song and clapped our hands.

As I said boys and girls tended to play separately but at party time we all got together. Pass the Parcel, Round Goes the Bun, Postman's Knock and Dooking for Apples were party favourites. Round Goes the Bun was played at most parties. It gave us a chance to kiss the girls and not make them cry. We all sang a little song and clapped our hands.Round goes the bun, the jolly old bun,

Round goes the bun once more

And he/she kneels to the prettiest girl/boy in the room

And kisses her/him on the floor.

Since we normally didn't get to kiss the girls anywhere, never mind on the floor, some juvenile Casanovas made the most of parent sanctioned intimacy. Some boys thought it was a bit sissy to kiss the girls but were generally forgiven in the party atmosphere. (By the way, I don't think they were suggesting we should kiss the boys) I remember after a party at Lily Kelly's being egged on to write a letter to her sister, Peggy, professing my undying love and offering to take her out. To make it official I posted the letter. Unfortunately I only had a halfpenny which didn't cover the cost of postage. I stuck the stamp on the letter and posted it anyway. There was a rumour Mr Kelly had to pay excess postage (a penny) and told his neighbours if he caught the one who sent the letter he would box his ears. For days afterwards I lived in fear of being found out, even though I hadn't signed my name. Of course nothing happened but it goes to show how small things loom large in a child's mind.

The stories that follow are about John Street in those days during WW2, when the John Street Heroes ruled the roost (or so we believed).

_________________________________________________

The John Street Heroes by Warwick Dalzell is on Amazon. (Kindle). It is a collection of stories about a gang of young boys who lived in Northern Ireland during the Second World War.

Looking across the rear gardens of John Street towards Scrabo Hill with the smoke from the Ulster Printworks and at the top left a rugby match in progress. Find out more at: www.newtownards.info/john-street.

© Warwick Dalzell 2015